A Survey on the Prevalence of Bovine Trypanosomosis in Bahir Dar Zuria and Bure Woreda, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia

Shemsia M*

Bahir Dar Animal Health Diagnostic and Investigation Laboratory, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia.

*Corresponding Author

Mohammed Shemsia,

Bahir Dar Animal Health Diagnostic and Investigation Laboratory, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia.

E-mail: Mohammedshemsia@gmail.com

Received: March 08, 2019; Accepted: April 17, 2019; Published: April 18, 2019

Citation: Shemsia M. A Survey on the Prevalence of Bovine Trypanosomosis in Bahir Dar Zuria and Bure Woreda, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Int J Vet Health Sci Res. 2019;7(1):230-235. dx.doi.org/10.19070/2332-2748-1900045

Copyright: Shemsia M© 2019. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

A study was conducted from November 2007 to April 2008 in Bahir Dar zuria woreda of tsetse free and Bure woreda of tsetse infested area of Amhara region of Northwest Ethiopia to investigate the prevalence of trypanosomosis in cattle. In each study area randomly selected cattle were sampled and their blood investigated using parasitological methods. The diagnostic techniques used include PCV (packed cell volume) to measure the degree of anaemia, heamatocrit centrifugation techniques (buffy coat examination) and thin smear. A total of 600 cattle (300 from Bahir Dar zuria woreda and 300 from Bure woreda) were sampled. Among them 80 cattle 45 (15%) in Bure woreda and 35 (11.66%) in Bahir Dar zuria were positive for trypanosome infection. The species of trypanosome infected during the study were Trypanosoma vivax (64%) and Trypanosoma congolense (36%) in Bure woreda but only Trypanosoma vivax (100%) were found in Bahir Dar zuria woreda. No significance difference in susceptibility was seen between male and female but significant differences in infection rate were observed between ages. Trypanosome infections were mainly due to Trypanosoma vivax and the significantly reduced the average packed cell volume and the body condition of the animals. The study revealed that trypanosomosis in cattle is an important disease in Amhara region of Northwest Ethiopia.

2.Abbreviations

3.Introduction

4.Materials and Methods

4.1 Study Area

4.2 Study Animals and Management

4.3 Study Design and Methodology

4.4 Parasitological and Hematological Examinations

4.4 Data Management and Analysis

5.Results

5.1 Parasitological Findings

5.2 Heamatological Findings

5.3 Trypanosome Infection Measurement and Their Linkage with PCV and BCS

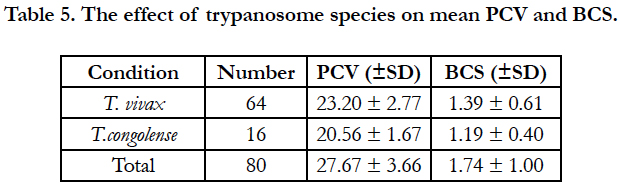

5.4 Effect of Trypanosome Species on Mean PCV and BCS

5.5 Trypanosome Infection and their Link with Age and Sex

6.Discussions

7.Conclusion and Recommendationss

8.References

Keywords

Bahir Dar; Bovine; Bure; Ethiopia; North West; Prevalence; Trypanosomosis.

Abbreviations

PCV: Packed Cell Volume.

Introduction

Bovine trypanosomosis causes a significance loss in animal production and it greatly hampers people and animal settlement in a considerable part of the world. Trypanosomosis that occurs across more than a third of Africa is arguably the most significance disease and there for remains as a major important constraints to livestock production on the continent [1].

In sub Saharan Africa, about 3 million livestock die every year due to tsetse fly transmitted trypanosomosis. 10 million km2 areas of the Africa's greatest agricultural potential are infested with tsetse fly, which is the main vector of the disease. The wide occurrence of this disease in people and their livestock retards agricultural and economic development in Africa and 30% of the continent cattle population, estimated to be 160 million and comparable numbers of small ruminants are at risk from trypanosomosis [1].

In Ethiopia, trypanosomosis is one of the most important disease limiting livestock productivity and agricultural development due to its high prevalence in the most arable and fertile land of South West and Northwest part of the country following the greater river basins of Abay, Omo, Ghibe and Baro with a high potential for agricultural development.

Currently, about 22,000 km2 areas of the above mentioned regions are infested with 5 (five) species of tsetse flies namely, G. Pallidipes, G. Moristans, G. fuscipes, G. Tachinoides and G. Longipennis [2].

Trypanosomosis of cattle (locally known as “GENDI”) can be found in mainly provinces of Ethiopia where it has greatly hindered development [3]. The most important trypanosome species affecting livestock in Ethiopia are T. congolense, T. vivax and T. bruce in cattle, sheep and goats, T. evansi in camels and T. equiperdum in horses [2]. Animals infected with trypanosomosis develop fever, anemia, lose of weight and progressively become weak and unproductive. Breeding animals frequently abort or may become infertile. Severely affected animals die of anemia, congestive heart failure or inter current bacterial infections that frequently take advantage of the weakened immune system [2]. If trypanosomosis could be controlled in Ethiopia much of the best watered and most fertile lands of South West could be utilized. At present, there are two principal approaches to control trypanosomosis in Ethiopia. These are control the vector, notably tsetse flies, and prevention or treatment of animals using trypanocidal drugs [2].

Tsetse flies are found mainly in five regional states of the country (Oromia, Southern people nations and nationalities, Gambella, Benishangul Gumuz regional states). As a result of tsetse born trypanosomosis threat, a large proportion of the livestock population is forced to reside in tsetse free high lands but environmentally and economically fragile [2, 3].

Many articles are published with regard to livestock trypanosomosis and its impact on livestock production in Ethiopia. In Ethiopia, amongst the disease constraint to livestock production, trypanosomosis is at the moment the greatest menance both interms of direct infliction of disease on livestock and prohibiting any sound and safe agricultural development over large expanse of otherwise fertile valleys in West and Southwest part of the country [4]. The Amhara bureau of agriculture and rural development has already prepared a control strategy for three years. Applying control program of tsetse and trypanosomosis regionally, evaluating the effectiveness of the control program and identifying the challenges of the control strategy were the main objectives of the control program. The targets of the control program are reducing the problem of tsetse and trypanosomosis by 80% from the current status and then improve the productivity of livestock and agricultural activity as well as facilitate access and provide live animals for marketing purpose and facilitating settlers from draught prone areas to their settlement sites suitable and profitable. Assessment of bovine trypanososmosis after the year control measures applied was important to measure the effectiveness of control strategy in selected areas of the region. Therefore; the objectives of the study was to assess the prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis in selected woredas under different tsetse challenge.

The study area was located in the Amhara regional state, Northwest Ethiopia. Geographically the region is located between North latitude 90 211 and 140 201 and East longitude 300 201 and 400 201. The region covers an area of approximately 170,000 km2 and is divided into 11 administrative zones. It is characterized by high plateaus, mountains and broad valleys. The annual mean temperature for most parts of the region is 15-21°C. Relatively high temperature is observed at some valleys and marginal areas exhibiting arid climates (low kola) the mean annual temperature of low kola sometimes exceeds 27°C. Amhara national regional state is the land of diverse topography with altitude ranging from 500 at Metebia to 4620 meters above sea level at Ras Dashen. Based on attitude it divided in to 3 agro-ecological zones Dega (25%), Woinadega (44%) and Kola (31%), respectively [5][5]

The livestock population of the Amhara region comprises about 10.6 million cattle, 5.7 million sheep, 4 million goat’s, 12 million equines and 17.4 thousands camels. The study area is densely populated with estimated average human population density of about 100 persons per km2. More than 90% of the population lives in rural areas and practice subsistence rain fed cropping combined with extensive grazing of livestock. Approximately 30% of the land area is cultivated, 12% is used for grazing, and 19% is forest and bush, 26% is unproductive land and 13% is classified as an utilizable land [5].

Part of the Amhara region is tsetse infested. Glossina moristans sub moristans and Glossina tachinoides are present. The samples were collected from Bure woreda (tsetse infested) which is located at the edge of tsetse belt with an altitude of 1500-2070 m.a.s.l and Bahir Dar zuria woreda which is tsetse free with an altitude of 1800 m.a.s.l. and surface area of 4191.68 km2 [2].

The study populations were indigenous zebu cattle population of all age group. The cattle involved in the study area were maintained under traditional management system. These were comprised of cattle belonging to several owner’s and were herded together each morning looked after by herds man during the day and return to their individuals owner’s homestead each evening. In Bure woreda herds grazed together and obtained water from near Zengena River that was tsetse infested area. In Bahir Dar zuria woreda herds grazed and obtained water from Abay river and Lake Tana especially during dry season the grazing area is restricted to banks of the river system. The main feed of cattle in the study was natural pasture. During the dry season cattle were fed on crop residues [6].

Cross sectional survey was conducted to determine the prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis. The sampling method applied was random sampling. Parameters like sex, age and body condition score were recorded for each individual animal during sample collection. The age of animal was determined by dentition [7] and categorized into two age groups (adult and young) and the body condition score was grouped in to poor, medium and good conditioned animals based on the appearance of ribs and dorsal spines applied for Zebu cattle [8]. To determine sample size, a bovine trypanosomosis prevalence rate of 16.15 was used for cattle in and around Bahir Dar from previous works by Mihret [9] and 7.3% expected prevalence for cattle in tsetse infested zone of Amhara region by Cherent et al., [3] for Bure woreda was taken into consideration to calculate sample size. The formula for estimating sample size was that of cited in Thrusfield [10] as follows:

N = Zα2/d2 pexp(1-Pexp)

Where, Zα = the normal distribution value for a given confidence level, N = required sample size, pexp = expected prevalence, d = desired absolute precision at 5%.

Hence, for Bahir Dar zuria woreda 16.1% expected prevalence, 95% confidence level and 5% precision resulted in a minimum sample of 263 samples. Similarly, 7.3% expected prevalence, 95% confidence level, 5% precision for Bure woreda gave us minimum 104 sample size. However to improve the degree of precision, a total of 300 samples from each study sites were taken.

Blood samples were examined by dark ground (DG) buffy coat microscopic method to detect the presence and species of trypanosomes as described by Murray et al., [11]. Blood samples were obtained by puncturing of the marginal ear vein with a lancet and collected directed into a capillary tube, which has been treated with heparin sealed one end with ‘Cristaseal’ (Hawksely). The capillary tubes were placed in micro haematocrit centrifuge with the sealed and outer most. After screwing the rotary cover and closing the centrifuge lid, the specimens were allowed to centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for minutes. Tubes were then placed in hematocrit and expressed the reading as a percentage of packed cells to the total volume of whole blood. Animals with PCV < 24% were considered to be anemia. Heamatocrite tubes were cut by diamond tipped pencil few millimeters a below the junction of the buffy coat/plasma level and erythrocyte/, the content homogenized on to a clean glass slide and coverage with a 22 x 22 mm cover slip. The slides were examined under a microscope using under 40 objective lens and x10 eyepiece for the movement of parasite [11].

Thin blood smears also done. A small drop of a blood from a microhaematocrtie capillary tube to the slide was applied to clean slid and spread by using another slide at angle of 450. The smear was dried by waving it in the air and fixed for 2 minutes in methyl alcohol, flood with Gimesa stain (1:10 solution) for 30-60 minutes and dried and washed (the excess stain) using distilled water. Allowed it to dry by standing up right on the rack and examined under the microscope (x100) oil immersion objective lens [11].

At the time of sampling the owner’s name, animals age, sex and body condition score were recorded using animal health data collection format. Hematological and parasitological data were handled similarly. Data on individual animals and parasitological examination results was inserted in to MS excel sheets programs to create a data base and transferred to SPPS soft ware programs of the computer before analysis [12]. Descriptive statistics, confidential interval, student - t test and Chi-square analysis were used to express results and comparable variables. The variables rate of trypanosome infection was calculated as the number of parasitological positive animals as examined as Buffy coat method [11] divided by the total number of animals investigated at the particular time. Confidence interval (95%) for the PCV of trypanosome infected and non infected were calculate. Student - t test was utilized was utilized to compare the mean PCV of the parasitic animals with that of parasitic animal.

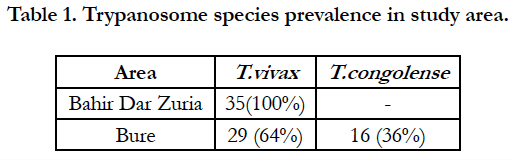

Between November 2007 to April 2008, a total of 600 heads of cattle (300 in Bahir Dar zuria woreda and 300 in the Bure woreda) were sampled. A total of 80 cattle (35 in the Bahir Dar zuria woreda, and 45 in the Bure woreda) were found to infected. The average parasitological prevalence was 11.6% and 15% in Bahir Dar zuria woreda and Bure woreda, respectively. The majority of trypanosome infections in the study area were infection due to T. vivax (Table 1). In Bure woreda T. congolense and T. vivax were the main trypanosome species.

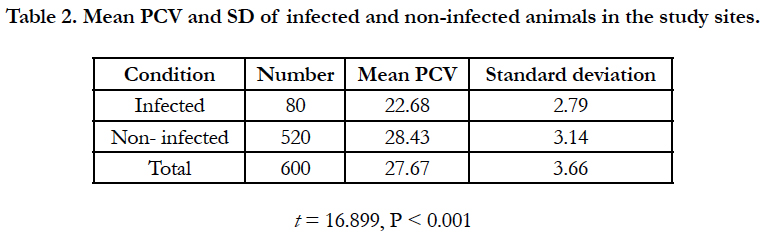

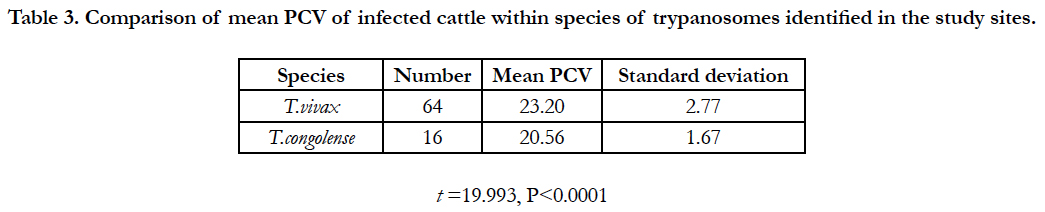

The main PCV of infected animals was significantly lower (P<0.001) than PCV of non-infected animals (Table 2). When anaemic condition was measured by mean PCV of parasitaemic period when infected, both T. vivax and T. congolense infection reduced PCV, relative to uninfected animals. T. congolense reduced significantly higher PCV to T. vivax infection (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of mean PCV of infected cattle within species of trypanosomes identified in the study sites.

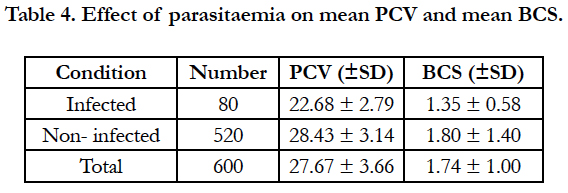

In study sites, there was significance effect when trypanosomes were detected on PCV and BCS. Trypanosome infection consistently depressed PCV. Animal never detected parasitaemic had significantly higher mean PCV values and significantly BCS than those parasitamic animals. The BCS of cattle infection with trypanosome was significantly lower (P < 0.005) than that of parasitological negative animals (Table 4).

T. congolense reduced significantly higher PCV and BCS relative to T. vivax infection (Table 5).

The prevalence of trypanosome infection differed between age categories. In general, there was low prevalence infection in young animals than adult animals and the difference was statically significant (P<0.05). The prevalence of trypanosome infection was higher in male than female animals. The prevalence was 13% and 14.5% for female male, respectively. But this was not statically significant (P>0.05).

Discussion

The results suggest that trypanosomes are an important disease of cattle in Amhara region. The presence of trypanosomes infection in Bure woreda (tsetse infested) was higher than the prevalence of trypanosomes infection Bahir Dar zuria woreda (tsetse free) but lower than other tsetse infested region of Ethiopia that observed by Ademe and Abebe [13] with a prevalence rate of 37% in Kodo Koysa woreda of Southern Ethiopia. This may be due to the location of our sampling site. The sampling was conducted on the edge of the tsetse belt where the density and thus tsetse challenge could be expected to be low. The average prevalence of trypanosome infection in Bahir Dar zuria woreda was in agreement with the observed by Tefere [14] with a prevalence rate of 12.27% in two district of Western Gojjam but lower than the one observed by Mihret [7] with prevalence rate of 16.1% in and around Bahir Dar. Chernet et al., [3] reported prevalence of 7.3% from Bure woreda before the implementation of the new trypanosomosis control proposal. Comparing to the present’s study, which was aimed to assess the conditions after one year, there were an increment of prevalence in the Bure woreda (tsetse infested area) while a significant reduction in Bahir Dar zuria woreda where it is tsetse free.

Bure woreda is tsetse infested where both the cyclically transmitted T. congolense was identified beside T.vivax. The control of trypaosomosis, predominantly by use of trypanocides, could result in failure of the drug to eliminate the parasite completely. Several studies [15, 16] have indicated T. vivax is highly susceptible to treatment while the problem of drug resistance is higher in T. congolense. The presence of many drug venders, and drug administration largely by unprofessional in the presence of T. congolense in the Bure woreda may explain the increase in prevalence even the control strategies are still taking on.

The higher proportion of T. vivax infection in Bure woreda contrasts sharply with trypanosome species prevalence data from other tsetse infested region of Ethiopia where T. congolense is the most prevalence species in cattle. Abebe and Jobre [17] report a prevalence rate of 58.5% for T. congolense and 31.2% for T. vivax in Southwest Ethiopia. Different workers [18, 19] reported a prevalence of 17.2%, 21% and 17.5% in Metekel district, Southern rift valley and upper Didessa valley of tsetse infested region, respectively and the dominant species was T. congolense. Trypanosomosis caused by T. vivax is the major animal health problem in both tsetse infested area and tsetse free area, followed by T. congolense.

T. vivax was a dominant species in both study area. The higher proportion of T. vivax infections in cattle sample in infested selection Bure woreda was attributed to the location of the study sites which was located on the edge of tsetse belt are usually less favorable resulting in high mortality rate of tsetse and favoring the transmission of trypanosome species with a short developmental cycle such as T. vivax [2, 20-22]. ILRAD [1] have reported that as the distance from recognized edge f tsetse belt areas increase, the species of trypanosomes most encountered and diagnosed is T. vivax because T. vivax has the ability to adopt and establish itself in the absence of tsetse belt and transmitted by other biting flies. The reason why T. congolense where absent in Bahir Dar zuria woreda. This is attributed to the fact that these trypanosome species established themselves more in cyclical transmission in the tsetse infested area than tsetse free. This has also been reported by Leak [23] that greater proportion of infections are transmitted mechanically rather than cyclically in such area (tsetse free) and T.vivax is more readily transmitted in this manner than other trypanosome species.

The higher proportion of T.vivax in Bahir Dar zuria woreda was in in agreement with the one reported by [17] in the high lands (tsetse free area) of which 99% of is due to T.vivax and Cherent et al., [3] in the same area. As it has been reported Temesgen [6], there are tsetse flies in the border for the two woreda and Ankesha Guagessa near the border of Zengena River. Here, they caught an number of Glossina moristans at the altitude of 1750 meters above sea level, the reason why Trypanosoma congolense were detected in Bure woreda.

Anemia is one of the most indicators of trypanosomosis in cattle [24]. In both study areas, trypanosome infection resulted in a significant decline in PCV. Similar results reported by Mihret [9] in and around Bahir Dar. A significance difference in PCV of cattle due to trypanosomosis is available in various studies carried out so far [17, 25, 26]. This variation in PCV would be important if considered with the aspect of predisposing factors to trypanosome infection. Trypanosomosis positive animals had poor body condition in this study which was in agreement with the study conducted by Cherent et al., [3]. No signify difference was observed between sexes and similar results were reported by different workers [9, 14, 27].

Age was found to be one of the risk factors in the present finding. A higher infection rate was observed in adult animals and animals above two years of age in the study area. This could be associated to the fact animals travel long distance for grazing and draught as well as harvesting crops to tsetse challenge areas. Rowlands et al., [16] in Ghibe valley indicated that suckling calves don’t go out with their dams but graze at home stead’s until they are weaned off. Young animals are also naturally protected to some extent by maternal antibodies [28]. This could result in low prevalence of trypanosome that was observed in calves.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In general, from this study we can conclude that trypanosomosis is an important disease and a potential threat in affecting the health and productively of cattle in economically important Amhara region of Northwest Ethiopia. Trypanosomosis prevalence showed increment in Bure (tsetse infested area) while there were significant reduction in the Bahir Dar zuria woreda (tsetse free area) after one year new control initiative. Infection with trypanosomosis negatively affected PCV and body condition score of cattle. This indicated that trypanosome infection of cattle in the study areas causes loss of body weight and production. This survey result has shown that there are T. vivax and T. congolense. In Bure woreda, in case of T. congolense mainly transmission is by tsetse flies so that in the future tsetse fly survey tsetse control should be carried out in this woreda. In the study woreda, the main trypanosomosis control method applied was chemotherapy, but there were many complain of the failure of trypanocidal drug to cure the disease in most of the study areas where unqualified practitioners or the owners themselves did the treatment. It is not unlikely practice, with consequential development of resistance of the parasite. Therefore based on the above conclusion the following recommendations are forwarded.

• Study should be conducted on the economic impact of the disease.

• Control of tsetse flies and trypanosomosis done by government should be continued.

• Community participation and awareness creation should be important for the proper implementation and sustainability of control programs.

• Veterinary service should be expanded for the proper application of the control programs.

• Introduction of drug administration legislation could alleviate the possible existence of drug resistance.

References

- ILRAD 1993-1994 Annual Report. The international laboratory for research on animal disease report Nairobi. 1994.

- Langridge WP. A tsetse and trypanosomiasis survey of Ethiopia. Ministry of Overseas Development (UK): Ministry of Agriculture of the Ethiopia; 1976. p. 1-40.

- Cherenet T, Sani RA, Panandam JM, Nadzr S, Speybroeck N, van den Bossche P. Seasonal prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis in a tsetse-infested zone and a tsetse-free zone of the Amhara Region, north-west Ethiopia. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2004 Dec;71(4):307-12. PubMed PMID: 15732457.

- Uilenberg G, Boyt WP. A field guide for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of African animal trypanosomosis. FAO: Rome,Italy; 1999.

- CSA. Agricultural Sample Survey, Statistical Bulletin, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2000.

- Temesgen A. Gojjam region tsetse and trypanosomiasis survey report. National tsetse and trypanosomiasis investigation center Bedle. 1987.

- DeLahunta A, Habel RE. ‘Teeth’. In A DeLahunta & RE Habel (eds.). Applied Veterinary Anatomy, n.p., W.B. Saunders Company: Philadelphia; 1986

- Nicholson MJ, Butterworth MH. A guide to condition scoring of zebu cattle. ILRI (aka ILCA and ILRAD); 1986.

- Adane M. Survey on the prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis in and around Bahir Dar. DVM Thesis, AAU, FVM, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 1995.

- Thrusfield M. Veterinary epidemiology. 3rd. Cambridgck e, USA: Blak Well Science Ltd. 2005:225-8.

- Paris J, Murray M, McOdimba F. A comparative evaluation of the parasitological techniques currently available for the diagnosis of African trypanosomiasis in cattle. Acta Trop. 1982 Dec;39(4):307-16. PubMed PMID: 6131590.

- Statistical Package for Social Studies (SPSS). SPSS 11.5.0 for windows, Lead Technologies Inc, USA. 2002.

- Ademe M, Abebe G. Field study on durg resistance trypanosomes in cattle (Bos indicus) in Kindo Koysha woreda, Southern Ethiopia. Bull Anim Hlth Prod. 2001;48:131-138.

- Terefe G, Abebe G. Prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis in two weredas of western Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region. Journal of Ethiopian Veterinary Association. 1999:1-8.

- Leak SG, Mulatu W, Authie E, D’Ieteren GD, Peregrine AS, Rowland GJ, et al. Epidemiology of bovine trypanosomosis in the Gibe valley, Southern Ethiopia. Tsetse challenge and its relationship to trypanosome prevalence in cattle. Acta Trop. 1993 Apr;53(2):121-34. PubMed PMID: 8098898.

- Rowlands GJ, Mulatu W, Authié E, d'Ieteren GD, Leak SG, Nagda SM, et al. Epidemiology of bovine trypanosomiasis in the Ghibe valley, southwest Ethiopia. 2. Factors associated with variations in trypanosome prevalence, incidence of new infections and prevalence of recurrent infections. Acta Trop. 1993 Apr;53(2):135-50. PubMed PMID: 8098899.

- Abebe G, Jobre Y. Trypanosomiasis: a threat to cattle production in Ethiopia. Revue de Médecine Vétérinaire. 1996;147(12):897-902.

- Afewerk Y, Clausen PH, Abebe G, Tilahun G, Mehlitz D. Multiple-drug resistant Trypanosoma congolense populations in village cattle of Metekel district, north-west Ethiopia. Acta Trop. 2000 Oct 2;76(3):231-8. PubMed PMID: 10974163.

- Tewelde N. Study on the occurrence of drug resistant trypanosomes in cattle in the farming in tsetse control areas (FITCA) project in Western Ethiopia. Addis Ababa University, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ethiopia MSc Thesis. 2001.

- Kidanemariam A, Hadgu K, Sahle M. Parasitological prevalence of bovine trypanosomosis in Kindo Koisha district, Wollaita zone, south Ethiopia. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2002 Jun;69(2):107-13. PubMed PMID: 12233995.

- Roeder PL, Scott JM, Pegram RG. AcuteTrypanosoma vivax infection of ethiopian cattle in the apparent absence of tsetse. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1984 Aug;16(3):141-7. PubMed PMID: 6485103.

- Jordan AM. Trypanosomiasis control and African rural development. London; New York: Longman; 1986. p. 357.

- Leak SG. Tsetse biology and ecology: their role in the epidemiology and control of trypanosomosis. ILRI (aka ILCA and ILRAD) Wallingford, Oxon, UK: CABI publishing; 1999. p. 152-210.

- Stephen LE. Trypanosomiasis: a veterinary perspective. Wheaton, London. 1986:1-551.

- Defly A, Awuome K, Bokovi K, D'Ieteren GD, Grundler G, Handlos M, et al. Effect of trypanosome infection on livestock health and production traits in two areas of Togo. In livestock production in tsetse affected areas of Africa. ILCA/ILRAD proceedings: Kenya; 1987. p. 251-256.

- D'Ieteren GD, Authié E, Wissocq N, Murray M. Trypanotolerance, an option for sustainable livestock production in areas at risk from trypanosomosis. Rev Sci Tech. 1998 Apr;17(1):154-75. PubMed PMID: 9638808.

- Aklilu N. Study on Bovine Trypanosomosis in Selected Sites of Central and Western Tigray, Ethiopia. DVM Thesis, FVM, AAU, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 2002.

- Fimmen HO, Mehlitz D, Horchiners F, Korb E. Colostral antibodies and Trypanosoma congolense infection in calves. Trypanotolerance research and application GTZ. 1999;116:173-8.