Community Psychology Linking Individuals and Communities into a Scientific Psychological Framework: An Integrative Approach

Ganaie, S.A1*, Shah S.A1, Nahvi N.I1, Chat A.N1

1 PG Department of Psychology, University of Kashmir, Hazratbal, J&K, 190006. India.

*Corresponding Author

Ganaie Showkat A,

PG Department of Psychology,

University of Kashmir,

Hazratbal, J&K, 190006. India.

E-mail: rcirehabilitationpsychologist@gmail.com

Article Type: Review Article

Received: November 17, 2014; Accepted: January 07, 2015; Published: January 13, 2015

Citation: Ganaie,S.A, Shah S.A, Nahvi N.I, Chat A.N (2015) Community Psychology Linking Individuals and Communities into a Scientific Psychological Framework: An Integrative Approach. Int J Translation Community Dis. 3(1), 46-54. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2333-8385-150009

Copyright: Ganaie, S.A© 2015. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Community psychology is a scientific discipline within the broad field of psychology which deals with mental health and social welfare issues of the community taking a holistic, systems-based approach to understanding behavior and how people fit in to society, much like related fields such as sociology and social psychology. Community psychology tends to be more centered on applying psychological and social knowledge to solving problems, creating real-world solutions and taking immediate action. Community psychologists primarily work in agency settings. Whether working in community health clinics involving in counseling practices and mental health work, or working in government or large social service agencies and doing research on existing social problems or planning and implementing grass roots social service programs. Their work is primarily with the marginalized and less-advantaged areas of society and those who struggle with poverty and discrimination amongst many other social ills. The primary purpose of a these psychologists is to strive for the wellbeing of an individual and society as a whole and to prevent issues from growing and treating them if they exit. The main focus of community psychologists are empowerment, social justice and wellness and prevention programs in community. These are all very broad areas of work that educate citizens to help themselves, their families and their communities to improve both their present and future. Despite the progress that has been made in Community Psychology since 1960s there is still much more improvement to be made. Societies are becoming increasingly diverse and with the continuing economic fluctuations many groups are becoming more and more marginalized. Community psychologists are working hand-in-hand with community members to identify and rectify problems as they arise and will continue to increase our knowledge regarding the society and improve the prosperity, health, well-being and lifestyles of society. Researchers have proposed one conceptual model for community crisis intervention for its development.

2.Introduction

3.History

4.Definitions

5.Scope of Community Psychology

5.1 Prevention of Mental Health Disorders

6.Psychological Crisis Intervention

6.1 Definition

6.2 Purpose

6.3 Description

6.4 Responses to Crisis

6.5 Education

6.6 Coping and Problem Solving

6.7 Purpose of Suicide Intervention

6.8 Assessment

6.9 Treatment Plan

6.10 Critical incident stress debriefing and Management

6.11 Purpose of CISD

6.12 Precautions

6.13 Medical crisis counseling

7.Models of Community Psychology

7.1 Mental Health Model

8.Proposed Community Intervention Model

8.1 Pre-crisis

8.2 During-crisis

8.3 Post-crisis

9.Application of PCCIM

10.Current Trends in Community Psychology

11.Conclusion

12.Acknowledgements

13.References

Keywords

Community Psychology; Social Change; Marginalized; Mental Health; Prevention; Scra & Intervention.

Introduction

Community psychology is a special area within the broad field of psychology which is concerned with how individuals relate to their society and community. It is fairly a broad and far reaching applied discipline, synthesizing elements from other disciplines including sociology, community development, ecology, public health, anthropology, cultural and performance studies, public policy, social work and social justice movements. Through community research and action, community psychologists produce knowledge that can inform social policies, social service work, helping practices and community change. This subdivision of psychology is fundamentally concerned with the relationship between social systems and individual well-being in the community context. One of the most exciting aspects of this field is that it is developing rapidly and is in the process of defining itself.

Community psychology is concerned with person environment interactions and the ways society affects individual and community functioning. It focuses on social issues, social institutions, and other settings that influence individuals, groups, and organizations. Community psychology as a science seeks to understand relationships between environmental conditions, the development of health and well being of all members of a community. Its practice is directed towards the design and evaluation of ways to facilitate psychological competence and empowerment, prevent disorder and promote constructive social change. The goal is to optimize the wellbeing of individuals and communities with innovative and alternative interventions designed in collaboration with affected community members and with other related disciplines inside and outside of psychology.

Community psychology is like public health in adopting a preventive orientation. Community psychologists try to prevent problems before they start, rather than waiting for them to become serious and debilitating. It differs from public health in its concern with mental health, social institutions, and the quality of life in general. In many ways, it is like social work, except that it has a strong research orientation. These psychologists are committed to the notion that nothing is more practical than rigorous, well-conceived research directed at social problems. Community psychology is also like social psychology and sociology in taking a group or systems approach to human behavior, but it is more applied than these disciplines and more concerned with using psychological knowledge to resolve social problems. It borrows many techniques from industrial and organizational psychology, but tends to deal with community organizations, human service delivery systems, and support networks. It focuses simultaneously on the problems of clients and workers as opposed to the goals and values of management. It is concerned with issues of social regulation and control, and with enhancing the positive characteristics and coping abilities of relatively powerless social groups (minorities, children, and the elderly).

Community psychologists simultaneously emphasize both (applied) service delivery to the community and (theory-based) research on social environmental processes. They focus, not just on individual psychological make-up, but on multiple levels of analysis; from individuals and groups to specific programs to organizations and finally to whole communities. Community psychology covers a broad range of settings and substantive areas. A community psychologist might find himself conducting research in a mental health center on Monday, appearing as an expert witness in a courtroom on Tuesday, evaluating a hospital program on Wednesday, implementing a school-based program on Thursday, and organizing a community board meeting on Friday. For all the above reasons, there is a sense of vibrant urgency and uniqueness among community psychologists, as if they are as much a part of a social movement as of a professional or scientific discipline. Thus, community psychologists grapple with an array of social and mental health problems and they do so through research and interventions in both public and private community settings. Psychologists working in this field look at the cultural, economic, social and political and environment that shape and influence the lives of people over the globe. The focus of this field can be both on applied and theoretical, but it is oftentimes a mixture of both. While some community psychologists conduct research on theoretical issues, others take this information and put it into immediate use to identify problems and develop solutions within communities.

The Community Psychology Major provides rigorous academic preparation for students who wish to pursue careers in human services, community development, mental health, family and youth programs, counseling, prevention, program evaluation, community arts, multicultural program development and human relations. The major also prepares students for graduate and post graduate work in a variety of academic and applied research fields including Psychology, Sociology, Counseling, Public Health, and Social Work as well as interdisciplinary work in the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences including Cultural Studies and Policy Studies. According to James G. Kelley, it is important that community psychologists exhibit several important qualities. First, it is important for these professionals to become part of the communities that they are trying to change. They must also embrace diversity, since their work places them in close contact with people from all walks of life. Finally, he must also be prepared to face challenges and deal with limited resources. In order to effect change in a community, these professionals often have to make the best of what is available and seek out new ways to gain assistance and build partnerships within the community.

History

In the 1950s and 1960s, many factors contributed to the beginning of community psychology in the United States of America. Some of these factors include:

- A shift from socially conservative, individual-focused practices in health care and psychology into a progressive period concerned with issues of public health, prevention and social change after World War II and social psychologists growing interest in racial and religious prejudice, poverty and other social issues.

- The perceived need of larger-scale mental illness treatment for soldiers with Mental Health Problems and Injuries.

- Psychologists questioning the value of psychotherapy alone in treating large numbers of people with mental illness.

- The development of community mental health centers and deinstitutionalization of people with mental illnesses into their communities.

- Community psychology began to emerge during the 1960s as a growing group of psychologists became dissatisfied with the ability of Clinical Psychology to address broader social issues. Today, many recognize a 1965 meeting of psychologists at the Swampscott Conference as the official beginning of contemporary community psychology. At this meeting, those in attendance concluded that psychology needed to take a greater focus on community and social change in order to address mental health and well-being. Since that time, the field has continued to grow.

- The Society for Community Research & Action (SCRA; Division 27 of the American Psychological Association) is the official organization of community psychology (website: Home – Society for Community Research and Action – SCRA or http://www.scra27.org. The Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA) is an international organization devoted to advancing theory, research, and social action. Its members are committed to promoting health and empowerment and to preventing problems in communities, groups, and individuals.

There are four broad principles guide SCRA:

- Community research and action requires explicit attention to and respect for diversity among peoples and settings;

- Human competencies and problems are best understood by viewing people within their social, cultural, economic, geographic, and historical contexts.

- Community research and action is an active collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and community members that uses multiple methodologies.

- Change strategies are needed at multiple levels in order to foster settings that promote competence and well being. The specific goals of the Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA) are:

- To promote the use of social and behavioral science to enhance the well being of people and their communities and to prevent harmful outcomes;

- To promote theory development and research that increases our understanding of human behavior in context;

- To encourage the exchange of knowledge and skills in community research and action among those in academic and applied settings

- To engage in action, research, and practice committed to liberating oppressed peoples and respecting all cultures;

- To promote the development of careers in community research and action in both academic and applied settings. The SCRA is also publishing newsletter of Community Psychologist.

- Several historical academic journals are also devoted to the Community Psychology, including the American Journal of Community Psychology, the Journal of Community Psychology, the Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, Journal of Community, Work and Family, Journal of Rural Community and Community development, Journal of Applied Behavioral Science and Journal of the Community Development, Development Society, Environment & Behavior [6,14,15,22,23].

Definitions

According to [8,10] “community psychology is about understanding people within their social worlds and using this understanding to improve people's well-being. Some of the topics addressed include substance abuse and prevention, addressing poverty issues, school failure, community development, risk and protective factors, empowerment, diversity, delinquency, and many more”.

According to the American Heritage Medical Dictionary (Stedman 2001, 2001 & 1995), “The application of psychology to community programs for the prevention of mental disorders and the promotion of mental health”.

According to Dorland's Medical Dictionary for Health Consumers (Saunders 2007), “community psychology a broad term referring to the organization of community resources for the prevention of mental disorders”.

Scope of Community Psychology

The scope of community psychology is vast because of its uniqueness to deal with community members, families, social groups, cultural groups, client populations, courts of law, policy makers, educators, leaders, prevention experts and community researchers etc. It is a specialized branch of psychology which deals with human and community development in general. The main objective of the community psychology is to prevent mental disorders and prescribe psychosocial interventions at community level to make community members effective contributors in community development.Community psychologists are also conducting prevalence, epidemiological and other types of research related to community. They can work in community mental health centers (CMHC), General Hospitals (GHs), Psychiatric Hospitals (PHs), mental health clinics (MHCs), research centers (RCs), and rehabilitation Centers (RCs), educational institutions (EIs), social welfare departments (SWDs), nursing homes (NHs), sports injury centers (SICs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) at regional, national and international level.

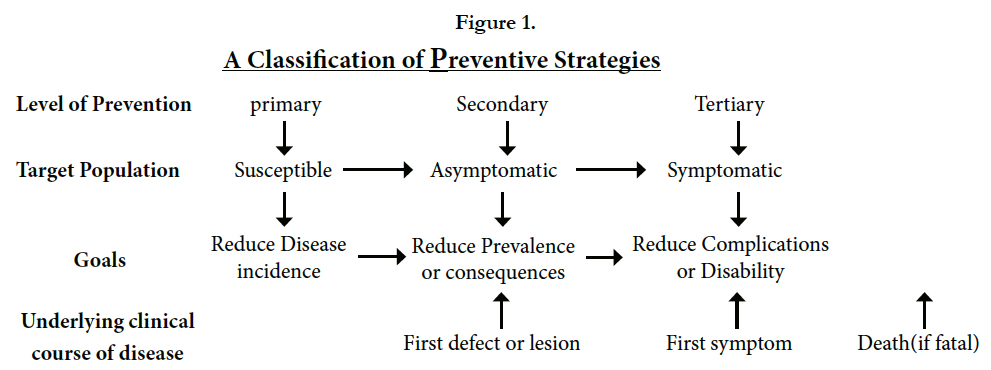

The goal of psychology and medicine is to promote and to preserve health, to restore health when it is impaired and to minimize suffering and distress. These goals are embodied in the word "prevention" which is often divided into three levels.

Primary prevention is concerned with preventing the onset of disease, to reduce the incidence of disease and the interventions that are applied before there is any evidence of disease or injury. Examples include protection against the effects of a disease agent, with proper vaccinations. It can also include changes to behaviors such as cigarette smoking or diet. The strategy is to remove causative risk factors (risk reduction), which protects health and so overlaps with health promotion.

Primary prevention may be aimed at individuals or communities. Individual approaches (encouraging your patient to stop smoking) have the advantages that the clinician's personal contact should be motivational; the message can be tailored to the patient and support can be given which will help in to reduce the smoking. Or also teaching him the ill effects of smoking and how dangerous it can to his as well others related to him. Therefore, a community or population approach (e.g. via mass media advertising, increasing taxes, or banning smoking in public places) tries to change risk factors in the whole population. It is more radical and may produce cultural and contextual changes that may support individual efforts. Examples of primary prevention include smoking cessation, preserving good nutritional status, physical fitness, immunization, improving roads, or fluoridation of the water supply as a way to prevent dental caries. These are the roles of health promotion and public health. A successful primary prevention programme requires that we know at least one modifiable risk factor, and have a way to modify it.

Secondary prevention is concerned with detecting a disease in its earliest stages, before symptoms appear, and intervening to slow or stop its progression: "catch it early." The assumption is that earlier intervention will be more effective, and that the disease can be slowed or reversed. It includes the use of screening tests or other suitable procedures to detect serious disease as early as possible so that its progress can be arrested and, if possible, the disease eradicated. An example is the Pap test to screen for cancer of the cervix, or a PSA blood test for prostate cancer; other instances include teaching people about the early signs of disease that they should watch for, and what type of treatment to seek. This is the task of preventive medicine.

Screening is central to secondary prevention because it is the process by which otherwise unrecognized disease or defects are identified by tests that can be applied rapidly and on a large scale. Screening tests distinguish apparently healthy people from those who probably have the disease. To be detectable by screening, a disease must have a long latent period during which the disease can be identified before symptoms appear (link to discussion of natural history) [39]. This is the purpose of screening tests. Implicitly, secondary prevention is used when primary prevention has failed.

Tertiary prevention refers to interventions designed to arrest the progress of an established disease and to control its negative consequences: to reduce disability and handicap, to minimize suffering caused by existing departures from good health, and to promote the patient's adjustment to irremediable conditions. "Minimize the consequences." This extends the concept of prevention into the field of clinical medicine and rehabilitation.

There is also a concept of "Primordial prevention" which seeks ways to "avoid the emergence and establishment of the social, economic and cultural patterns of living that are known to contribute to an elevated risk of disease. This would include environmental control of disease vectors, and eliminating predisposing factors such as illiteracy and maternal deprivation (JM Last, Dictionary of Public Health).

An obvious criticism of medical care is that it tackles health issues without addressing their underlying determinants. The pattern of health problems can be expected to continue until someone addresses health determinants.

Psychological Crisis Intervention

Crisis intervention refers to the methods used to offer immediate, short-term help to individuals who experience an event that produces emotional, mental, physical, and behavioral distress or problems. A crisis can refer to any situation in which the individual perceives a sudden loss of his or her ability to use effective problem-solving and coping skills. A number of events or circumstances can be considered a crisis: life-threatening situations, such as natural disasters (such as an earthquake or tornado), sexual assault or other criminal victimization; medical illness; mental illness; thoughts of suicide or homicide; and loss or drastic changes in relationships (death of a loved one or divorce) [1].

Crisis intervention has several purposes. It aims to reduce the intensity of an individual's emotional, mental, physical and behavioral reactions to a crisis. It helps individuals return to their level of functioning before the crisis. Functioning may be improved above and beyond this by developing new coping skills and eliminating ineffective ways of coping, such as withdrawal, isolation, and substance abuse. In this way, the individual is better equipped to cope with future difficulties. Through talking about the incidents which occurred and the feeling associated with it and developing ways to cope and solve problems, crisis intervention aims to assist the individual in recovering from the crisis and to prevent serious long-term problems from developing. Research documents positive outcomes for crisis intervention, such as decreased distress and improved problem solving.

Individuals are more open to receiving help during crises. A person may have experienced the crisis within the last 24 hours or within a few weeks before seeking help. Crisis intervention is conducted in a supportive manner. The length of time for the intervention may range from one session to several weeks, with the average ofl four weeks. Crisis intervention is not sufficient for individuals with long-standing problems. Session length may range from 20 minutes to two or more hours. Crisis intervention is appropriate for children, adolescents, and younger and older adults. It can take place in a range of settings, such as hospital emergency rooms, crisis centers, counseling centers, mental health clinics, schools, correctional facilities, and other social service agencies. Local and national telephone hotlines are available to address crises related to suicide, domestic violence, sexual assault, and other concerns. They are usually available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

A typical crisis intervention progresses through several phases. It begins with an assessment of what happened during the crisis and the individual's responses to it. An individual's reaction to a crisis can include emotional reactions (fear, anger, guilt, grief), mental reactions (difficulty concentrating, confusion, nightmares), physical reactions (headaches, dizziness, fatigue, stomach problems), and behavioral reactions (sleep and appetite problems, isolation, restlessness). Assessment of the individual's potential for suicide and/or homicide is also conducted. Also, information about the individual's strengths, coping skills, and social support networks is obtained.

There is an educational component to crisis intervention. It is critical for the individual to be informed about various responses to crisis and that he or she has normal reactions to an abnormal situation. The individual is also instructed about the responses being temporary. Although there is not a specific time that a person can expect to recover from a crisis, an individual can help recovery by engaging in the coping and problem-solving skills described below.

Other elements of crisis intervention include helping the individual understand the crisis and their response to it as well as becoming aware of and expressing feelings, such as anger and guilt. A major focus of crisis intervention is exploring coping strategies. Strategies that the individual previously was acknowledged with but that have not been used to deal with the current crisis may be enhanced or bolstered. Also, new coping skills may be developed. Coping skills may include relaxation techniques and exercise to reduce body tension and stress as well as writing down these thoughts and feelings instead of keeping them inside. In addition, options for social support or spending time with people who provide a feeling of comfort and caring are addressed. Another central focus of crisis intervention is problem solving. This process involves thoroughly understanding the problem and the desired changes, considering alternatives for solving the problem and discussing its pros and cons, selecting a solution and developing a plan to try it out, and evaluating the outcome. Cognitive therapy, which is based on the notion that thoughts can influence feelings and behavior, can be used in crisis intervention.

In the final phase of crisis intervention, the professional will review changes the individual made in order to point out that it is possible to cope with difficult life events. Continued use of the effective coping strategies that reduce distress will be encouraged. Also, assistance will be provided in making realistic plans for the future, particularly in terms of dealing with potential future crises. Signs that the individual's condition is getting worse or "red flags" will be discussed. Information will be provided about resources for additional help should the need arise. A telephone follow-up may be arranged at some agreed-upon time in the future.

Suicidal behavior is the most frequent mental health emergency. The goal of crisis intervention in this case is to keep the individual alive so that a stable state can be reached and alternatives to suicide can be explored. In other words, the goal is to help the individual reduce stress and survive the crisis [2].

Suicide intervention begins with an assessment of how likely it is that the individual will kill himself in the immediate future. This assessment has various components. The professional will evaluate whether or not the individual has a plan for how the act would be committed, how deadly the method is (shooting, overdosing), if means are available (access to weapons), and if the plan is detailed and specific versus vague. The professional will also assess the individual's emotions, such as depression, hopelessness, hostility and anxiety. Past suicide attempts as well as completed suicides among family and friends will be assessed. The nature of any current crisis event or circumstance will be evaluated, such as

loss of physical abilities because of illness or accident, unemployment, and loss of an important relationship.

A written safekeeping contract may be obtained. This is a statement signed by the individual that he will not commit suicide, and agrees to various actions, such as notifying their clinician, family, friends, or emergency personnel, should thoughts of committing suicide again arise. This contract may also include coping strategies that the individual agrees to engage in to reduce distress. If the individual states that he or she is not able to do this and then it may be determined that medical assistance is required and voluntary or involuntary psychiatric hospitalization may be implemented. Most individuals with thoughts of suicide do not require hospitalization and respond well to outpatient treatment. Educating family and friends and seeking their support is an important aspect of suicide intervention. Individual therapy, family therapy, substance abuse treatment, and/or psychiatric medication may be recommended [3].

Critical incident stress debriefing (CISD) uses a structured, small group format to discuss a distressing crisis event. It is the best known and most widely used debriefing model. Critical incident stress management (CISM) refers to a system of interventions that includes CISD as well as other interventions, such as one-on-one crisis intervention, support groups for family and significant others, stress management education programs, and follow up programs. It was originally designed to be used with high-risk professional groups, such as emergency services, public safety, disaster response, and military personnel. It can be used with any population, including children. A trained personnel team conducts

this intervention. The team usually includes professional support personnel, such as mental health professionals and clergy. In some settings, peer support personnel, such as emergency services workers will be part of the debriefing team. It is recommended that a debriefing occur after the first 24 hours following a crisis event, but before 72 hours have passed since the incident.

This process aims to prevent excessive emotional, mental, physical, and behavioral reactions and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from developing in response to a crisis. Its goal is to help individuals recover as quickly as possible from the stress associated with a crisis. There are seven phases to a formal CISD which are as under:

- Introductory remarks: team sets the tone and rules for the discussion, encourages participant cooperation.

- Fact phase: participants describe what happened during the incident.

- Thought phase: participants state the first or main thoughts while going through the incident.

- Reaction phase: participants discuss the elements of the situation that were worst.

- Symptom phase: participants describe the symptoms of distress experienced during or after the incident.

- Teaching phase: team provides information and suggestions that can be used to reduce the impact of stress.

- Re-entry phase: team answers participants' questions and makes summary comments.

Some concern has been expressed in the research literature about the effectiveness of CISD. It is thought that as long as the provider(s) of CISD have been properly trained, the process should be helpful to individuals in distress. If untrained personnel conduct CISD, then it may result in harm to the participants. CISD is not psychotherapy or a substitute for it. It is not designed to solve all problems presented during the meeting. In some cases, a referral for follow-up assessment and/or treatment is recommended to individuals after a debriefing

Medical crisis counseling is a brief intervention used to address psychological (anxiety, fear and depression) and social (family conflicts) problems related to chronic illness in the health care setting. It uses coping techniques and building social support to help patients manage the stress of being newly diagnosed with a chronic illness or suffering a worsening medical condition. It aims to help patients understand their reactions as normal responses to a stressful circumstance and to help them function better. Preliminary studies of medical crisis counseling indicate that one to four sessions may be needed. Research is also promising in terms of its effectiveness at decreasing patients' level of distress and improving their functioning.

Models of Community Psychology

The mental health model, which has its roots in the community mental health movement, is based on the explicit intention to prevent mental illness and its consequent disruption of the usual patterns of living. It seeks to strengthen, conserve and develop human resources in order to prevent mental disorder [7,21,25,27]. By increasing the coverage and impact of services, and the possibility of more people receiving help sooner, this approach seeks to alleviate the ever-mounting pressure on mental hospitals. This represents a shift from the waiting-mode of mainstream psychotherapeutic practice [20,30].

Preventative efforts move beyond the exclusive treatment of individual patients towards various ecological levels that include entire populations or small groups and organizations within them [24]. The efforts include not only the mentally ill, who may or may not avail themselves for treatment, but also the healthy [19]. It is designed to alleviate harmful environmental conditions, avoid unnecessary psychic pain and to strengthen the resistance of communities to inevitable future stressful experiences. Rather than merely redressing deficit and pathology, it focuses on the development of competencies and coping skills. Prevention may be utilized to plan and implement programmes for reducing the incidence of mental disorders of all types in the community (primary prevention); the duration of a significant number of those disorders which do occur (secondary prevention); the impairment which may result from those disorders (tertiary prevention) [16].

According to Bloom [24] primary intervention efforts may take on three different forms; the population wide approach; the milestones model; and the high risk group approach [8,13]. Secondary prevent aims to, “identify and treat at the earliest possible moment so as to reduce the length and severity of disorder” [12,24]. By way of early detection, it promotes growth-enhancing programmes that are geared to reduce problems before they become severe. It is really a treatment based strategy that strives to make available more services to the community. For this process to gain momentum, it must also be accompanied by an increase in the utilization of services by the community [31].

Tertiary prevention strives to minimize the degree and severity of disability by preventing relapses among recovered patients. It endeavours to ensure that ex—patients are offered maximum support for rehabilitation and re—integration into the community. It attempts to reduce obstacles that may hinder the full participation of ex-patients in the occupational and social life of the community. Half-way houses and after-clinics all aim to foster tertiary prevention [19].

Cautions that prevention programmes “may not change our current social institutions but might add on to them ... and might add with little evidence that they actually prevent anything” (p. 18) [35]. Prevention programmes can also become a new arena for colonialization with people being forced to consume the goods and services of the psychologists. Prevention efforts assume the existence of universal values in the catchment area, but ignore how such consensus about these values may be reached[31].

Promoting prevention requires a conceptualization of mental health that moves beyond a mere semantic shift. The new definition does not simply equate mental health with the absence of mental illness. Instead, it moves beyond individuals so as to take cognizance of the broader social and economic stresses created by their contexts [4,5,24]. According to White [31] any such definition transcends beyond using the concept health as a metaphor. Despite differences in outlook, all definitions entail some conception of growth and development, of autonomy and individuality as well as some conception of relatedness to one’s environment [31].

In keeping with its emphasis on prevention and positive mental health this approach superficially attempts to understand people within their total personal and social environments rather than as isolated human beings [20]. However, it does not attempt to underplay the role of the individual’s psyche and trauma. It asserts that mental illness is the product of an interaction of both individual and environmental factors. In essence, the model attempts to locate the seat of pathology at the interface of the interaction between individuals and their environment. Thus far, it has failed to provide a theoretical base for such a conception of pathology. Consequently it has to revert to established explanations of mental illness based on the individual model. Without a theory of pathology, it is almost inevitable that its treatment strategies are conventional crisis intervention and consultation.

Consultation refers to the provision of technical assistance by an expert to individuals or groups on aspects pertaining to mental health [29]. It is essentially an indirect, “within systems” strategy which aims at modifications, renewal or improvement of existing social institutions or environments. It seeks to create some remediation and basis for change in the environments represented by consultees, in a manner that fosters the positive mental health of clients.

This approach, according to [18] contains the potential of maximizing the limited amount of person-power available. This can be achieved by fully exploiting the roles of the natural care-givers in the community. Natural care-givers include people like health nurses, teachers, parents and ministers who are physically and psychologically available. Based on a geographical conception of community, this model is committed to rendering mental health services to an entire community through a community mental health centre [31]. The role of the psychologist in this setting is

that of a professional, rendering expert services to a client population.

The social action approach, which has its foundations in the “War on Poverty” strategy [34] arose out of discontent with structural inequities and the unresponsiveness of the political apparatus of American society. Like the mental health approach it is initially aimed at prevention, but from a radically different perspective.

Located within the Community Action Programme, the poverty- programme addressed itself to the needs of the poor and to the complex nature of interrelated social problems. Thus, in its Endeavour to equalize opportunities for upward social mobility, it sought to make available more social resources to the ‘poor’. It simultaneously attempted to alter the social and psychological characteristics of the poverty-stricken in order to prepare them for more meaningful participation in society [17].

This model criticizes traditional psychology’s individualist orientation that locates pathology solely within individuals. It asserts that it is imperative to take cognizance of the structural inequities of society, which may include factors like inadequate housing, overcrowding, the absence of free speech and political powerlessness (Brown, 1978; Reiff, 1968, [31]). The shift is from prevention to empowerment. [36] argues that empowerment should be “the call to arms”. While prevention is founded on the needs approach, empowerment is based on a “rights” model. Accordingly, Rappaport asserts that because many competencies are already present in people, what is required is a release of potential. “Empowerment implies that what you see as poor functioning is a result of social structure and lack of resources which make it impossible for the existing competencies to operate” [37].

By including power in its explanatory model, the emphasis shifts from “blaming the victim” to implicating the social arrangements of society. This means that a pre-requisite for empowerment is a redressing of social inequalities. This model conceptualizes community process and inter-group relations in terms of conflicting interests between groups. Accordingly it argues that the poor do not have any power, influence or control in the society. Since the dominant group has vested interests in maintaining political and economic inequities, differences are not easily reconcilable. Logically then, social action advances the mobilization and organization of an “appropriate constituency” to exert pressure on the

ruling elite ([24], Reiff, 1968, cited in Mann, 1978). In the South African context it would probably involve organizing the un-enfranchised, with a view to shifting the power balance and instituting structural changes [11,32,33].

By arguing that health is not possible in the context of repression and domination, social action programmes address themselves to issues of finance, power, increasing resources, education and community development. Reiff [31] asserts that self-determination must be an integral part of any social action programme. The acquisition of power is a pre-requisite for the fulfillment of human needs. For him, the powerlessness of the poor renders selfactualization unrealistic. It is imperative that the working-class experience themselves as being able to determine what happens to them, both as individuals and as a group [26]. Some theorists have pointed out that in order to advance and maintain this process

of self-determination, community psychology should be a social movement rather than a professional enterprise. Confirmation for this position is provided in the added thrust that community psychology gained from being juxtaposed with a series of civil rights and youth protest actions during the 1960’s in the United States of America [31].

In accordance with its view on the acquisition of power, this model stresses and encourages community participation and equality in community relations, relying on grass-roots support for its programmes. Establishing a power base and commanding grass-roots support are vital, for as [6,24] implicitly points out the dis-empowered cannot achieve their goal without struggle.

In accordance with its tenet of self-determination and community control, this model has devised various strategies to foster a sense of power and community participation. This is achieved by increasing community morale, tapping community resources, developing social skills and generating opportunities for promoting local leadership (Lewis & Lewis, 1979; [31]).

As part of its intervention strategy, the social action approach capitalizes on natural support systems. It employs the services of “indigenous” non¬professionals and attempts to mobilize consumers of services to assume control of the activities of the programme [31]. Given the assumption that non-professionals are fairly sensitive to the needs of the community, they are considered to fulfill a good liaison function for the professional services. They are able to provide valuable input for programmatic planning and are also in a position to encourage the community to utilize the services [31]. It is argued that because they have the same social background as the clients, they are able to interact with a greater degree of therapeutic effectiveness. The amount of trust they receive and the emotional significance that they hold for the clients, allow them to render informal support and communication within the community itself (Guerney, 1969; Zax & Specter, 1974). Despite these advantages, experience the world over indicates that the professional/non-professional relationship is often unidirectional. Non-professionals are not always accorded equal status and are perceived to be in need of training and upgrading. The emphasis appears to be on incorporating the indigenous into a professional framework.

To foster independence, various multi-purposes, locally controlled, community development corporations (CDC’s) were established in ghetto and rural areas all over America. Functioning on a non-profit basis, these CDC’s have been able to promote economic and social development, as well as some degree of political power (Bower, 1973). They essentially provide a permanent source of income and collective power for the ghetto residents

and for the community as a whole. If programmes like the CDC’s are not an integral part of a broader movement, they run the risk of merely becoming little enclaves with greater scope for selfsufficiency and material advancement.

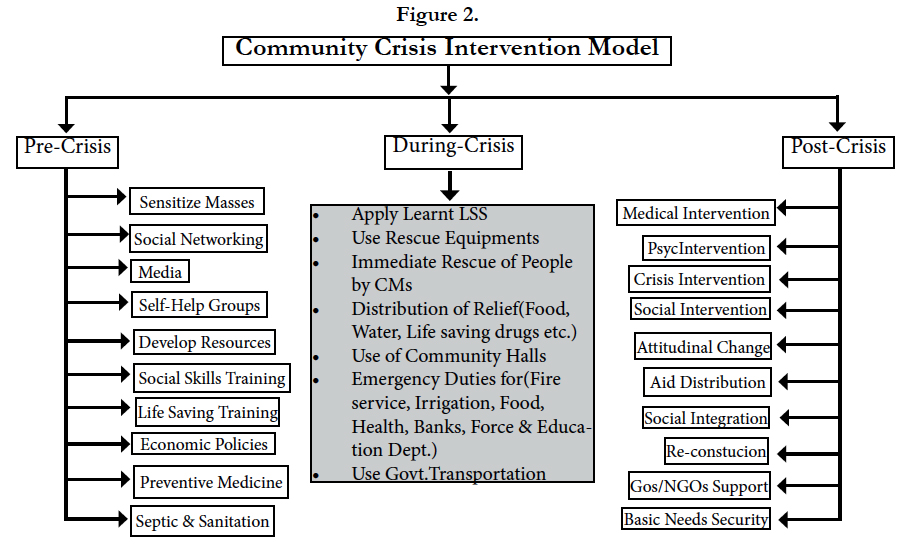

Proposed Community Intervention Model

Since there are many models of community intervention, the model which will be discussed in this article is a new one and has been developed by Ganaie, S.A., Shah, S.A., Nahvi, N.I. & Chat, A.N. (2014). This is a conceptual model and has been developed on the basis of crisis observation during the recent flashfloods in Jammu and Kashmir, India (September, 2014).The proposed Community Crisis Intervention Model (CCIM) is an integrative model which includes pre-crisis, during crisis and post-crisis interventions at community level. The researchers have followed the rinciples of Bio-Psycho-Social Model to design a new model especially for community crisis management. There are three stages of proposed CCIM which are as under:

In pre-crisis stage, masses will be sensitized about social skills, life saving skills and self help skills during crisis situations like floods, earth quakes & cyclones etc. in community. Information will be spread through media, self help groups and social networking sites. The self help groups of community members will be prepared for voluntary service delivery during crisis situations in community. All types of resources and aids will be collected and stored for crisis situations in community. This stage will be the crisis preparedness and prevention stage.

In during-crisis stage, all community members will apply skills which they have learnt in pre-crisis stage. All community members will take care of themselves and their family members. All the stored resources will be used to rescue people during crisis situations. Self help groups will also take part in rescue operation. Community halls can be used for temporary living. Some government departments and non-governmental organizations will work continuously during these crisis situations in community. Government transportation should be used to move people from crisis places to safer places and transportation of food, water, medicines and other essential things.

In post-crisis management stage, all types of interventions should be given to people affected by crisis. Most professionals should focus on medical, psychological and social interventions. Professionals who prescribe Interventions should try to reinforce positive attitudinal changes in community members which will finally lead to community development. The crisis intervention also includes crisis counseling which will help community members how and where to approach to fulfill the basic needs. NGOs and governmental organizations should work hand by hand to

rehabilitate community members who have been affected by crisis situation. Damaged infrastructures have to be re-constructed to improve the living standard of community members. The basic needs of the community members should be fulfilled with the help of community stored aid in pre-crisis and governmental & non-governmental support. These post-crisis management techniques will help community members in social inclusion, social

integration and restoration of community life.

Application of PCCIM

The proposed community crisis intervention model is an integrative model to rehabilitate communities before, during and post crisis situations in communities. The proposed model requires multi-disciplinary rehabilitation team. The team should be prepared from different sectors like Health & Medical Education, Para- medical, Social Sciences, Finance, Construction, Fire Service, Food & Supplies, Banking, Water Supplies, Flood Control and Non-Governmental Sector. When the inter-sectarian collaboration will happen to fight against the crisis situations in community naturally the impact of crisis will be reduced to a large extent. The proposed model can be used in different crisis situations like Floods, Earth Quakes, Cyclones, Wars and Epidemiological Diseases Control etc.

Figure 2: Community Crisis Intervention Model

*PCCIM by Ganaie, S.A., Shah, S.A., Nahvi, N.I., & Chat. A.N. (2014)

Current Trends in Community Psychology

The community psychology movement developed in the U.S.A. during an era when there was growing concern about both the lack of resources and treatment facilities and the impact of social systems on the human psyche. Psychologists and other helping professionals began to take note of the effects of social variables like poverty and alienation on mental health [28]. Modern community psychology is focusing on multiple aspects of individual and community development in general. Community psychology is fast developing discipline and concentrated on social and mental health needs of community members at community level. Community psychologists are busy to conduct research on incidence, prevalence and epidemiology of mental disorders in community. They are a part of policy making and development of special schemes for different sections of society. They are trying to reduce the social evils and issues which are responsible for poor mental health and social well-being of Community members and also providing specialized clinical and rehabilitation services to community members at community mental health centers.

Conclusion

Community psychology draws on interdisciplinary perspectives and approaches to examine social problems and promote the well-being of people in their communities. While the field draws heavily from psychology, it also draws from theory and practice in sociology, community development, ecology, public health, anthropology, cultural and performance studies, public policy, social work, and social justice movements. Through community research and action, community psychologists produce knowledge that can inform social policies, social service work, helping practices, and community change. There are few existed models of community psychology which can be used for community intervention like mental health model, social action model, organizational model and ecological model. Modern community psychologists should try to explore different variables related to health of community members and come up with new integrative models for community development. In present paper, researchers have proposed conceptual framework of community crisis intervention model for crisis management during disasters and crisis situations in community. The proposed model will be effective for community development because it covers maximum areas related to community development during crisis and disasters.

Acknowledgements

We thank to Ms. Asiya Chat, Tamseel Pandit, Fatima, Rukaya, Deepali Waga, Sayali Bondre & Mr. Bilal Shah, Imran Shah, & Shabir Ahmad from Department of Psychology University of Kashmir-Hazratbal.

References

- Aguilera, Donna C. (1998) Crisis Intervention: Theory and Methodology. (8th edtn), New York: Mosby.

- American Association of Suicidology. 4201 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 408, Washington D.C. 20008. (202) 237 2280. http://www.suicidology.org

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. 120 Wall Street, 22nd Floor, New York, New York, 10005. (212) 363-3500, or 888-333-AFSP. http://www.afsp.org

- Albee G.W (1980) A competency model to replace the defect model. In M. Giliss, G.R. Lachenmeyer & J. Segal (Eds.). Community Psychology; Theoretical and empirical approaches. Gardner Press, N.Y.

- Albee G.W, Joffe J.M, Dusenbury L.A. (Eds.) (1988). Prevention, powerlessness and politics: Readings on social change. Sage Publications. Newbury Park, Calif.

- Alinsky S (1971) Rules for radicals. New York: Random House.

- Anderson L. S (1966) Community psychology: A report of the Boston Conference on the Education of Psychologists for Community Mental Health. Boston University & Quincy Mass. South Shore Mental Health Center

- Barker F, Perkins (1981) Program maturity and cost analysis in the evaluation of primary prevention programs. Journal of Community Psychology 12(1):31-42.

- Barker R.G. (1964) Ecological psychology: Concepts and methods for studying the environment of human behavior. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Barker R. G, Schoggen P (1973) Qualities of community life (1st edtn),. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Berger S, Lazarus S (1987) The view of community organizers for the relevance of psychological practise in S.A. Psychology in Society 7:6-23.

- Bindman A. J, Spiegel A. D (Eds.). (1969) Perspectives in community mental health. Chicago: Aldine.

- Bloom B (1984) Community mental health: A general introduction. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Bower M (1973) The emergence of community development corporations in urban neighborhoods. In B. Donner & R. Price (Eds.). Community mental health: Social action and reaction. Holt, N.Y.

- Brown P (1978) Political, economic and professionalistic barriers to community control of mental health servides: A commentary on Nassi. Journal of Community Psychology 6(4):381-392.

- Caplan G (1974) Support systems and community mental health. Behavioral Publications.

- Carr S. C, Sloan T. S (Eds.) (2003) Poverty and psychology: From global perspective to local practice. New York: Kluwer Academic / Plenum.

- Caplan G (1984) Principles of preventive psychiatry. Tavistock, London.

- Caplan G, Grunebaum H (1970) Perspectives on primary preventions: A requiem. In P. Cook (Ed.). Community psychology and community mental health. Holden-Day, California.

- Connery R.H (1968) The politics of mental health. Organizing community mental health in metropolitan areas. Columbia University Press, N.Y.

- Dorken H (1969) Behind the scenes in community mental health. In AJ. Bindman & A.D. Spiegel, (Eds.). Perspective in community mental health. Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago.

- Duveen G, Lloyd B (1986) The significance of social identities. British Journal of Social Psychology 25:219-230

- Heather N (1976) Radical perspectives in psychology. Methuen, London.

- Heller K, Monahan J (1977) Community psychology and community change. Dorsey.

- Hobbs N, Smith M.B (1969) The community and the community mental health centre. In A.J. Bindman & A.D. Spiegel (Eds.),. Perspectives in community mental health. Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago.

- Hoffman C (1978) Empowerment movements and mental health: Locus of control and commitment to the United Farm Workers. Journal of Community Psychology 6(3):216-221.

- Hunter A, Riger S (1986) The meaning of community in community health. Journal of Community Psychology 14(1):55-71.

- Iscoe I, Spielberger C.D (1977) Community psychology: The historical context. In I. Iscoe, B.L. Bloom, & C.D. Spielberger (Eds.). Community psychology in transition. Proceedings of the national conference on training in community psychology. Hemisphere Publishing Company, N.Y.

- Lachenmeyer J (1980). Mental health consultation and programmatic changes. In M. Gibbs et al. (Eds.). Community psychology: Theoretical and empirical approaches. Gardner Press, N.Y.

- Lafollette J, Pilisuk M (1981). Changing models of community mental health services. Journal of Community Psychology 9(3):210-233.

- Mann P.A (1978) Community psychology: Concepts and applications. The Free Press, New York.

- Muller J (1985) The end of psychology: A review essay on “Changing the subject”. Psychology in Society 3:33-42.

- Muller J, Cloete N (1987) The white hands: academic social scientists, engagement and struggle in South Africa. Social Epistemology 1(2):141-154.

- Nassi A.J (1979) Community control or control of the community? The case of the community mental health centre. Journal of Community Psychology 6(1): 3-15.

- Rappaport J (1981) In praise of paradox: A social policy of empowerment over prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology 9(1):1-21.

- Rappaport J (1977) Community psychology: Values, research & action. NY: Holt, Rinehart, Winston.

- Rappaport J, Seidman E (2000) Handbook of community psychology. Plenum Press.

- Rappaport J, Swift C, Hess R (1984) Studies in empowerment: Steps toward understanding and action (Prevention in Human Services, 3 (2/3) Haworth. HM271.S878

- Reich S. M, Riemer M, Prilleltensky I, Montero, M (2007) International community psychology: History and theories. Springer.