A Clinical Perspective On Sexuality With Pregnancy and Postpartum

Redelman M*

Medical Sex Therapist, The Male Clinic, Australia.

*Corresponding Author

Dr. Margaret Redelman OAM,

Medical Sex Therapist, The Male Clinic, Australia.

E-mail: drmredelman@gmail.com

Received: April 21, 2017; Accepted: May 08, 2017; Published: May 11, 2017

Citation: Redelman M (2017) A Clinical Perspective On Sexuality With Pregnancy and Postpartum. Int J Reprod Fertil Sex Health. 4(3), 105-109. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2377-1887-1700018

Copyright: Redelman M© 2017. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

2.Prevalence of Female Sexual Dysfunction (FSD) Postpartum

3.Help Seeking Behaviour

4.Assisted Fertility

5.Sexual Concerns in First Year Postpartum

6.Woman’s Response to Pregnancy

7.Male Partner’s Postpartum Sexual Function

8.Resumption of Sexual Activity Postpartum

8.Effect of Pregnancy and Child Loss – Miscarriage, Ectopic Pregnancy, Vanishing Twin Syndrome & Stillbirth - On Sexuality

9.Management of Sexuality Around Pregnancy And Postpartum

10.Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercises

11.Conclusion

12.References

A Clinical Perspective on Sexuality with Pregnancy and Postpartum

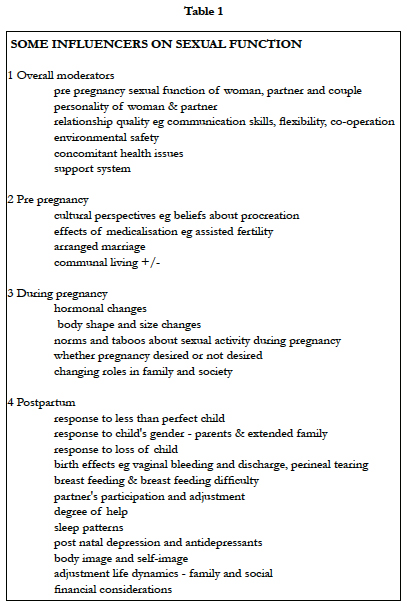

In taking a comprehensive psycho-sexual-relational history it is very common to hear that "sex was great until the birth of the first child". Therefore, it is very important to address sexual health in a way that prevents detrimental changes in women's and couples sexual lives. Proactive intervention through open discussion of normal sexuality and sexual concerns during this phase with provision of education and effective strategies is preferable to the unhappiness, pain and disruption that can result through denial of possible consequences. Not all women and couples experience negative sexual consequences as some women experience increased ease of orgasm, desire and general confidence with the birth of the child. However, almost all individuals benefit from affirmation that they are 'normal'. Good communication and co-operation around parenting can significantly increase the intimacy and valence of the relationship with flow on to sexuality and family wellbeing.

Sexuality is often not discussed during pre-and postpartum care. Often, the assumption is that a couple has adequate knowledge about sex and that it is enjoyable or good enough because a pregnancy has been achieved, that they will raise any problems, that someone else will address the sexuality component etc. Pregnancy and sexuality are both considered 'natural'. Yes, the instinct and performance of intercourse are largely natural but the enjoyable artistry of lovemaking is a learnt behaviour. Not many cultures actively teach creative lovemaking or educate about how to manage sexuality when changes occur.

Pregnancy and childbirth lead to many changes for the mother and father. Both individuals and the couple need to be considered and included in the management of their sex lives. Sexual problems during pregnancy and postpartum that are unresolved can trigger ongoing patterns of discord with detrimental consequences for the man, woman, couple, child and society. This is important because of the relationships between low sexual desire, low sexual activity frequency, relationship satisfaction, domestic violence and relationship and family stability. The postpartum period is often associated with a decline in couple's relationship satisfaction [1]. Relationship satisfaction drops for over 60% of couples in the first 3 years after a child is born [2, 3]. Intimacy which is the depth of exchange, both verbal and non-verbal, which implies a deep form of acceptance of the other as well as commitment to the relationship [4] is extremely important as a buffer for changes in sexual function. Low relationship satisfaction is highly correlated with low total relationship intimacy and poor sexual relationship [5]. Transition to parenthood can be both extremely pleasurable and extremely stressful and holistic proactive are should be given.

Prevalence of Female Sexual Dysfunction (FSD) Postpartum

The prevalence of FSD is generally reported as being between 10-40% [6, 7]. With the first pregnancy 40-70% of couples experience a drop in marital quality with marital conflict increasing, an increased risk of depression, individuals reverting to stereotypic gender roles, women being overwhelmed by childcare and housework, fathers withdrawing into work and decreased marital conversation and sexual activity [8]. And, 41-83% of couples still have difficulties at 2-3 months [9, 10].

The prevalence of FSD after childbirth has been reported to be 5-35% after caesarean section and 40-80% after normal vaginal delivery [11]. Australian research [12] showed that 64.3% of women experienced FSD and 70.5% sexual dissatisfaction during the first year after childbirth. The most prevalent FSDs were sexual desire disorder (81.2%), orgasmic problems (53.5%) and sexual arousal disorder (52.3%).

Help Seeking Behaviour

Research clearly shows that overwhelmingly the general population is still reticent to seek help with sexual matters. This pattern is also seen postpartum [12]. Olsson [13] reported that women's sexual issues are only addressed by a health professional after being raised by the woman herself. The postpartum check usually occurs at 6 weeks. However, it has been shown that the first 6 months have increased FSD [12, 14] so clinical practice needs to be adjusted to incorporate review of sexual function at 6 months.

The health professional needs to address sexual function as part of holistic care of the post partum woman and couple. If we accept that very few people receive a good sexual education and most have ‘adequate’ sex lives and we accept that pregnancy , birth and childcare affect sexual and relationship functioning then we need to accept being pro-active rather than re-active to protect and improve our patients' sexual function.

A study in a London teaching hospital [9] found that only 18% postpartum women received information about postpartum sexual changes although 69% had discussed the safe resumption date of sexual activity. Health professionals seem to be comfortable with discussing time of resumption of intercourse but not other sexual activities such as masturbation and outercourse. When we say "no sex" because not good for the pregnancy, baby or woman, we need to be very specific as to what is meant ie no intercourse, no outercourse, no masturbation, no kissing and cuddling. Patients scared by a medical situation and wanting to do everything possible to have a healthy baby often misinterpret what is said.

Assisted Fertility

Assisted fertility creates a whole spectrum of sexual concerns and difficulties for both members of the couple. This specialist assistance should automatically include sexuality help.

Sexual Concerns in First Year Postpartum

New parents worry about when to restart sexual intercourse, when to restart birth control, pain during intercourse, desire discrepancy between the partners [15-18] and the impact of body changes on sexual activity [19]. In one study, 89% of new mothers and 82% of new fathers had at least one postpartum sexual concern and approximately 50% of all new parents had multiple postpartum sexual concerns [15].

Woman’s Response to Pregnancy

Pregnancy may not be a desired or joyous experience for all women. And even when it is a joyous wanted event there are effects that are not so positive. Fatigue for 91% [20], nausea, change of shape and weight gain, stretch marks, varicose veins and not just in the legs but in such uncomfortable places as the labia, hip and back problems, feelings of being invaded or hijacked with loss of ownership of her body, changed attitudes in her partner, inclusion of health professionals in her life, loss of identity and submersion into 'mother’ with changes in her social status due to stopping work and loss of income generation and of course the pervasive covert or overt anxiety about the delivery and the health of the baby.

Despite these effects 90% of women are sexually active during the pregnancy with a decrease to 30% in the 9th month [21]. The given reasons for the decrease in desire are focus on the forthcoming event, physical discomfort, altered body image, fear of injuring fetus, cultural beliefs, and urinary incontinence. For a small percentage of women pregnancy is a time of increased sexualprowess and libido as pregnancy is an affirmation of sexuality and femaleness, confers increased status and possibly more arousal and increased ability to orgasm due to increased genital blood supply. The removal of contraception needs is generally perceived as a plus for sexuality.

Dyspareunia which is very common in the first 3-6 months postpartum and experienced by 45% of women at 2 months [9] is a major disincentive to genital activity. The mode of delivery has a demonstrated association with dyspareunia due to perineal tears, episiotomy and operative vaginal delivery. Caesarian delivery appears to decrease the incidence of dyspareunia in the first 3-6 months but has no further benefit [22]. However, other concomitant factors must be important as mode of delivery was not significant for sexual function in 29 identical twin pairs discordant for mode of delivery [23].

The degree of perineal trauma (24 has significant impact on sexual dysfunction. Women with 2° perineal tears had an 80% increased incidence of dyspareunia at 3 months postpartum and women with 3° and 4° tears had a 270% increased incidence of dyspareunia. Pelvic organ prolapse, urinary incontinence, and anal incontinence correlate significantly with sexual dysfunction [25, 26] and the importance of pelvic floor exercises during pregnancy and postpartum cannot be stressed enough as a way to decrease urinary and anal incontinence at 12 months [27].

Depression and sexual dysfunction are bi-directional. Forty percent of depressed women reported desire, arousal and orgasm disorders in a population–based cross-sectional study [28]. Postpartum sexual dysfunction is common in women with post natal depression and sexual activity re-starts later after childbirth in depressed women [2]. Depression is bi-directional with decreased sexual desire at 3 and 6 months [29].

Post natal depression begins 2-4 weeks after delivery and has an incidence of 10-15% with 40% recurrence in next pregnancy [30]. Puerperal psychosis affects 0.1-0.2% of women after childbirth [30]. However, resolution of the depression may not result in improvement of libido [31]. Most female sexual dysfunctions are multifactorial and the alterations in marital and family dynamics with childbirth and depression and the effects of medication to treat the depression need to be addressed in management. Antidepressant medication related sexual dysfunctions occur in 30-50% of patients [32].

Breastfeeding affects sexual function [2]. With lactation there is an increase in prolactin which leads to a decrease in androgens and estrogens which leads to a decrease in desire and vaginal lubrication. Perhaps even more importantly breastfeeding is tiring and time consuming with a lot of skin contact. The woman's need for skin contact with her partner may be decreased. The breasts themselves have changed in functional meaning from sensitive erotic symbols to a milk factory that leaks, feels different and may be sore if cracked. If the breasts have been a significant component of erotic play then the couple's sexual script has been disrupted.

Fatigue and sleep deprivation play havoc with any sexual needs. Many people make love last thing at night and are used to no interruptions. This change and learning to tolerate interruptions in love-making often needs assistance.

Standards of female physical beauty affect women's comfort with their bodies determining display behaviour. Dissatisfaction with post pregnancy physical appearance and weight gain is negatively correlated with sexuality.

Male Partner’s Postpartum Sexual Function

Men can have many new experiences during the journey to parenthood: fear of parenthood, fear of financial burden, fear of work or goal disruption, envy of partner's ability to become pregnant and bear a child, resentment of attention focused on partner, ‘couvade syndrome’ [33], fear of hurting the pregnant woman or fetus, resentment of losing sexual rights, sense of abandonment [34]. Later , jealousy of the child and shame about feeling this way together with loss of partner's time and attention can significantly alter their experience of the relationship.

There has been less research on male postpartum response to intimacy sexuality and marital satisfaction [17, 18]. Society tends to focus attention on the woman during pregnancy and then on the baby. Often the effect on the male of his lover's physical changes, libido drop, increased conservatism with love-making, changes in intimate and recreational needs are not considered. Men have to manage incorporating 'mother' into the 'lover' image and their self identity into family man and provider. Men can experience post natal depression [2] and there is a clinical need to be vigilant about this to prevent personal and relationship distress.

The modern trend has been to include the partner in the delivery but for some men this creates problems especially if he felt coerced into being present [35]. Men can respond with horror that they have caused such pain and experience changes in perception of the woman's sexuality and vagina/genitals [36] as erotic and attractive which can lead to consequences such as decreased desire and erectile difficulties.

Resumption of Sexual Activity Postpartum

The 6 week postnatal check is often seen as the signal to resume sexual activity and 52% do so with 90% having some intercourse by 3 months [37, 38]. A predictor of postpartum sexual dysfunction is not being sexually active by 3 months and later resumption of sexual activity (not just intercourse) should signal need for enquiry. Several studies have shown that primiparity has a negative impact on subsequent sexual function [12, 39, 40]. This could be related to birth difficulty especially the degree of vaginal tear [41].

There is significant variety in postpartum non intercourse behaviour [42] although male masturbation remained constant throughout and female masturbation remained constant throughout pregnancy, dropped to zero and gradually increased postpartum. Couples with good interpersonal communication and sexual skills will negotiate for non-penetrative activity which is enjoyable, satisfying and comfortable.

Effect of Pregnancy and Child Loss – Miscarriage, Ectopic Pregnancy, Vanishing Twin Syndrome & Stillbirth - On Sexuality

This is a situation where often the health professionals have difficulty communicating with the woman or couple. These difficult life realities can have significant psychosexual sequalae. They are hard for everyone to address, can be experienced differently by the two partners who may have different grieving styles. The partner's response is often discounted and they are left with little or no support or framework in which to settle themselves. The most common outcomes are despondency, anxiety and depression which can be expressed through withdrawal, acting out, association of sex with grief or sexual activity. Withdrawal from sensual activity between the couple through depression or fear of another pregnancy and repetition of loss deprives the couple of supportive intimacy and bonding over the joint loss.

The impact of the loss needs to be overtly discussed, different coping mechanisms exposed and a joint strategy implemented for healthy coping and resolution of the grief.

Management of Sexuality Around Pregnancy And Postpartum

Each individual and couple needs to be treated as unique and given the opportunity to voice their own concerns rather than be labeled with expected outcomes.

Generally the best predictor of postnatal sexuality is the prenatal sexuality. It is very important to establish the baseline function at the beginning of pregnancy. People in general have a very poor recollection of pre-event sexual function and seek to find a rational answer to every problem or change. A pregnancy or child becomes the obvious scapegoat.

Most health professionals acknowledge that sexuality is important and that pregnancy and the postpartum period can affect sex lives with long-term detrimental effects but stop short of instituting actions by self or others, via referral, to address this. Proactive discussion and education needs to be initiated early in the healthcare relationship to prevent negative consequences.

The woman and her partner (and it may be another woman) are both strangers to her 'new postpartum body ' and gentle re-exploration needs to take place. There is a need for repeated validation for the 'new body' and the new roles that both individuals are taking on. The partner is often left out of this validation and not acknowledged for the changes and pressures they are experiencing. Exploring of the 'new' status needs to start with the easiest steps such as making time and prioritizing self sensuality and sexuality with masturbation. Masturbation is a good starting point to learn what has changed and what is now needed to achieve arousal and orgasm. Religious and cultural sensibilities need to be sensitively accommodated. A temporary medical training attitude can be adopted. Slow progression with mutual masturbation and outercourse before progressing to intercourse allows for the reintroduction of couples sexual behaviour.

The sexual needs of the partner who has not experienced body and hormone changes need to be voiced and accommodated to prevent resentment and unwanted sexual behaviours.

It is helpful if the couple can discuss their beliefs about pregnancy and afterwards and what they believe will happen with their sexual life. This allows these beliefs to be understood by both partners and actually addressed. The health professional can help with encouraging realistic expectations especially with feeding patterns and fatigue. The degree of available help is often crucial in the adjustment of the couple. In modern life with small nuclear families living far from relatives this is often a problem.

The instinct for intercourse is universal so encouraging individuals to think about broadening their repertoire to include more outercourse options can be interesting. However, if they can accept that lovemaking can also be about sharing the intimacy of their bodies with each other, giving each other sensual and sexual pleasure and sharing orgasms together and that they can continue experiencing all these while the woman's body and energy levels heal, they may be more open to change. Neither needs to be sexually frustrated or feel rejected. Discussing sexual options and sexual positions is part of postnatal sexual care. Perineal pain and dyspareunia should be discussed at the same time as timing of initiation of sexual activity so that advice about vaginal lubricants, gentle digital exploration, outercourse, increased foreplay and woman on top position for initial penetration can be given. If there has been second or third degree perineal tearing, or there is urinary and fecal incontinence then some degree of sexual difficulty should be expected and flagged. Postnatal depression should always be screened for and it's bi-directional relationship with sexual difficulties understood. The negative sexual side effects of antidepressants need to be compensated for.

Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercises

The vast majority of women, if they have been told about doing pelvic floor muscle exercises, stop when they leave hospital or soon after. Pelvic floor muscle exercises can improve orgasmic potential in non-orgasmic women with poor pelvic muscle tone, improve desire, performance and achievement of orgasm [43]. It should be stressed that they should be done daily for life.

Conclusion

Research and intuitive conclusion is that sexuality can be and often is affected by the multitude of changes that come with achieving a pregnancy; being pregnant; delivering the child and the postpartum healing and adjustments to parenting. This is further compounded by the differing effects of this process on two genders, or in a lesbian couple it can be where one carried the child and the other did not. As many women's and couple's sexual difficulties originate around this life stage it is prudent for health professionals to pro-actively raise the spectre of pre-existing sexual difficulties and flag new potential issues. The well-being of the child depends on the well-being of the couple, and subsequently the well-being of society which otherwise has to retrospectively manage the fall-out of unhappy or broken relationships and thus affected children.

Raising and addressing sexuality issues is not complicated or onerous. It requires only the willingness of health professionals to include sexuality screening in their consultations and either up-skill themselves or have a source for referrals.

The most important aspect of clinically managing individuals during this period is to remember that they are individuals. Being open to respectfully listening to their past and present sexual histories and difficulties provides the basis on which to help them. It is very important to help our patients to help our patients maintain the habit of being sensual and sexual with each other enough to ride through this period and have a positive base from which to go forward.

References

- Hansson M, Ahlborg T (2012) Quality of the intimate and sexual relationship in first-time parents - a longitudinal study. Sex Reprod Heal. 3(1): 21–9.

- Morof D, Barrett G, Peacock J, Victor CR, Manyonda I, et al., (2003) Postnatal depression and sexual health after childbirth. Obs Gynecol. 102(6): 1318–25.

- Williamson M, McVeigh C, Baafi M (2008) An Australian perspective of fatherhood and sexuality. Midwifery. 24(1): 99–107.

- Gilbert SJ (1976) Self-disclosure, intimacy and communication in families. Fam Coord. 25(3): 221–31.

- Nezhad M Z, Goodarzi AM (2011) Sexuality, Intimacy & Marital satisfaction in Iranian First-Time Parents. J Sex Marital Ther. 37(2): 77–88.

- Laumann EO, Glasser D, Neves R, Moreira ED (2009) A population-based survey of sexual activity, sexual problems and associated help-seeking behaviour patterns in mature adults in the United States of America. Int J Impot Res. 21(3): 171–8.

- Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, Johannes CB, Sergeti A (2008) Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obs Gynecol. 112(5): 970–8.

- Gottman JM, Notarius CJ (2002) Marital research in the 20th century and a research agenda for the 21st century. Fam Process. 41(2): 159–97.

- Barrett G, Pendry E, Peacock J, Victor C, Thakar R, et al., (2000) Women’s sexual health after childbirth. BJOG. 107(2): 186–95.

- Glazener CM (1997) Sexual function after childbirth; women’s experiences, persistent morbidity and lack of professional recognition. Br J Obs Gynaecol. 104(3): 330–5.

- Khajehei M, Ziyadlou S, Safari M, Tabatababee HR (2009) A comparison of sexual outcomes in primiparous women experiencing vaginal and caesarean births. Int J Comm Med. 34(2): 126–30.

- Khajehei M, Doherty M, Tilley PJ, Sauer K (2015) Prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in postpartum Australian women. J Sex Med. 12(6): 1415–26.

- Olsson A, Robertson E, Falk K, Nissen E (2011) Assessing women’s sexual life after childbirth: The role of the postnatal check. Midwifery. 27(2): 195–202.

- Pauls R, Occhino J, Dryfhout V (2008) Effects of pregnancy on female sexual function and body image: A prospective study. J Sex Med. 5(8): 1915–22.

- Pastore L, Owens A, Raymond C (2007) Postpartum sexuality concerns among first-time parents from one US academic hospital. J Sex Med. 4(1): 115–23.

- Leeman LM, Rogers R (2012) Sex after childbirth: postartum sexual function. Obs Gynecol. 119(3): 647–55.

- MacAdam R, Huuva E, Bertero C (2011) Fathers’ experiences after having a child: sexuality becomes tailored according to circumstances. Midwifery. 27(5): e149–55.

- Olsson A, Robertson E, Bjorklund A, Nissen E (2010) Fatherhood in focus, sexual activity can wait: new fathers’ experience about sexual life after childbirth. Scand J Caring Sci. 24(4): 716–25.

- Mickelson KD, Joseph JA (2012) Postpartum body satisfaction and intimacy in first-time parents. Sex Roles. 67:300–10.

- Masoni S, Maio A, Trimarchi G, de Punzio c, Fioretti P (1994) The couvade syndrome. J Psychosom Obs Gynec. 15(3): 125–31.

- von Sydow K (1999) Sexuality during pregnancy and after childbirth: a metacontent analysis of 59 studies. J Psychosom Res. 47(1): 27–49.

- Barrett G, Peacock J, Victor CR, Mayonda I (2005) Cesarean section and postnatal sexual health. Birth. 32(4): 306–11.

- Botros SM, Abramov Y, Miller JJ, Sand PK, Gandhi S, et al., (2006) Effect of parity on sexual function: an identical twin study. Obs Gynecol. 107(4): 765–70.

- Signorello LB, Harlow BL, Chekos AK, Repek JT (2001) Postpartum sexual function and its relationship to perineal trauma: a retrospective cohort study of primiparous women. Am J Obs Gynecol. 184(5): 881–8.

- Handa VL, Cundiff G, Chang H, Helzlsouer KJ (2008) Female sexual function and pelvic floor disorders. 111(5): 1045-1052. Obs Gynecol. 111(5): 1045–52.

- Handa VL, Burgio KL, Fine PM, Brown MB, Weber AM, et al., (2007) The impact of fecal and urinary incontinence on quality of life 6 months after childbirth. Am J Obs Gynecol. 197(6): 636.el-6.

- Hay-Smith J, Cody JD, Boyler R, Morkved S (2012) Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment of urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10: CD007471.

- Johannes CB, Odom DM, Russo PA, Monz BU, Shifren JL, et al., (2009) Distressing sexual problems in United States women revisited: prevalence after accounting for depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 70(12): 1698–706.

- DeJudicibus MA, McCabe MP (2002) Psychological factors and the sexuality of pregnant and postpartum women. J Sex Res. 39(2): 94–103.

- Harris B (2002) Postpartum depression. Psychiatr Ann. 32: 405–33.

- Moel JE, Buttner MM, Gorman L, Stuart S, O'Hara MW (2010) Sexual function in the postpartum period: effects of maternal depression and interpersonal psychotherapy treatment. Arch Womens Ment Heal. 13(6): 495–504.

- Balon R (2006) SSRI–associated sexual dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry. 163(9): 1504–9.

- Khanobdee C, Sukratanachaiyakul V, Gay JT (1993) Couvade syndrome in expectant Thai fathers. Int J Nurs Stud. 30(2): 125–31.

- Figes K (2000) Life after birth. London: Penguin.

- Johnson MP (2002) The implications of unfulfilled expectations & perceived pressure to attend the birth on men’s stress levels following birth attendance: a longitudinal study. J Psychosom Obs Gynecol. 23(3): 173–82.

- Raphael-Leff J (2001) Pregnancy. The inside story. London: Karnac.

- Rogers RG, Borders N, Leeman LM, Albers LL (2009) Does spontaneous genital trauma impact postpartum sexual function? J Midwifery Womens Heal. 54(2): 98–103.

- Brubaker L, Handa VL, Bradley CS, Brown MB, Weber A, et al., (2008) Sexual function 6 months after first delivery. Obs Gynecol. 111(5): 1040–4.

- East C, Sherburn M, Ngle C, Said J, Forster D (2012) Perineal pain following childbirth: Prevalence, effects on postnatal recovery and analgesis usage. Midwifery. 28(1): 93–7.

- Thompson J, Roberts C, Currie M, Ellwood DA (2002) Prevalence and persistence of health problems after childbirth: Associations with parity and method of birth. Birth. 29(2): 83–94.

- Rathfisch G, Dikencik B, Kizilkaya Beji N, Comert N, et al., (2010) Effects of perineal trauma on postpartum sexual function. J Adv Nurs. 66(12): 2640–9.

- Von Sydow K, Ullmeyer M, Happ N (2001) Sexual activity during pregnancy and after childbirth: results from the Sexual Preferences Questionnaire. J Psychosom Obs Gynecol. 22(1): 29–40.

- Kizilkaya Beji N, Yalcin O, Erkan HA (2003) The effect of pelvic floor training on sexual function of treated patients. Int Urogynecol J. 14(4): 234–8.