Early Adjuvant Intravenous Vitamin C Treatment in Septic Shock may Resolve the Vasopressor Dependence

Nabil Habib T1*, Ahmed I2

1 Critical Care Department, Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt.

2 Clinical Pharmacy Specialist, Faculty of pharmacy, Alexandria University, Egypt.

*Corresponding Author

Tamer Nabil Habib,

Critical Care Department, Faculty of medicine,

Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt.

Email: tamer_zakhary@hotmail.com

Recieved: July 06, 2017; Accepted: July 25, 2017; Published: July 28 2017

Citation: Nabil Habib T, Ahmed I (2017) Early Adjuvant Intravenous Vitamin C Treatment in Septic Shock may Resolve the Vasopressor Dependence. Int J Microbiol Adv Immunol. 05(1), 77-81. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.19070/2329-9967-1700015

Copyright: Nabil Habib T© 2017. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Evidence is emerging that intravenous administration of high-doses of vitamin C may have beneficial effect and can be used as adjuvant therapy of severe sepsis and septic shock. The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of early intravenous high doses of vitamin C as adjuvant treatment in patients with septic shock. 100 patients with septic shock were enrolled, randomized into 2 groups. Early vitamin C (EVC) group (n=50) received intravenous 1.5 gm vitamin C (ascorbic acid) every 6 hours in the first 24 hours after admission until ICU discharge plus conventional sepsis treatment. Other 50 patients were enrolled as a control. The primary outcomes were the need for organ supportive measures and length of ICU stay. There were no differences in duration on MV (p= 0.187), need for RRT (p=0.412), or ICU mortality (p=0.138). The mean number of days on vasopressor was significantly less in EVC group than in control group (2.30 Vs 6.50 days, p=0.001). There was a statistically significant difference in ICU stay between the two groups (p=0.04). Early vitamin C in septic shock may resolve the vasopressor-dependent septic shock rapidly with no benefit on mortality.

2.Introduction

3.Methods

4.Results

5.Discussion

6.Conclusion

7.References

Keywords

Critical; Sepsis; Septic Shock; Vitamin C; Vasopressor.

Introduction

Sepsis as a life-threatening syndrome caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. The term septic shock includes patients with evidence of tissue hypoperfusion and organ dysfunction [1-3]. Septic shock is sepsis with underlying circulatory and cellular/metabolic abnormalities severe enough to substantially increase mortality. It is clinically defined as persistent hypotension requiring vasopressors to maintain mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥ 65 mm Hg and serum lactate level ≥ 2 mmol/L (18 mg/ dL) despite adequate volume resuscitation and associated with hospital mortality ≥ 40%. The global burden of sepsis and septic shock is about 15-19 million cases annually with a mortality rate around 60% in low income countries like Egypt [1]. New therapeutic approaches to septic shock are required to reduce its global burden but it should be effective, cheap and safe [4].

Vitamin C is water-soluble vitamin, involved in many metabolic processes. In healthy fasting humans, circulating level of ascorbate (the redox form of vitamin C) are in the range of 50-70 μmol/L [5]. In the intensive care setting, vitamin C is notorious for its strong antioxidant and immunomodulating activities. Vitamin C is adjuvant therapy in conditions associated by oxidative stress as ischemia-reperfusion disorders, trauma, and inflammatory disorders [6].

Evidence is emerging that intravenous administration of highdoses of vitamin C may have beneficial effect and can be used as adjuvant therapy of severe sepsis and septic shock [4]. An excessive inflammatory response indeed enhances the metabolic turnover of vitamin C. As a result, patients with septic shock often have very low plasma levels of vitamin C that sometimes enter the scurvy zone [7]. The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of early intravenous high doses of vitamin C as adjuvant treatment in patients with septic shock.

Methods

After ethical approval for this clinical trial from the local committee of ethics in the faculty of medicine of Alexandria university and the department of critical care, Informed consent was taken from all patients or their next of kin. This prospective controlled study was conducted on adult patients admitted to the critical care department with the diagnosis of septic shock. Septic shock was defined with the 3rd international consensus definition for septic shock and at least one positive culture. All Pregnant and lactating mothers were excluded. Any patients with a history of oxalate nephrolithiasis or in documented glucose- 6-phosphate dehydrogenase G6PD deficiency, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, and hereditary hemochromatosis were excluded.Any patient developed any other type of shock state or patients with mixed type of shock were excluded.

All enrolled patients who met the inclusion criteria (n=100) were randomized (even odd randomization technique) into the study. Studied patients (n=100) were divided into 2 equal groups (each consists of 50 patients). Early vitamin C (EVC) group: 50 septic shock patients received intravenous 1.5 gm vitamin C (Ascorbic acid, Cevarol) every 6 hours in the first 24 hours after admission until ICU discharge plus conventional sepsis treatment. Control group: 50 septic shock patients received conventional sepsis treatment only. Norepinephrine was the vasopressor of first choice and titrated to a dose of 20 μ/min targeting a mean arterial pressure > 65 mmHg. Conventional sepsis treatment in both groups was performed according to our hospital protocol.

All enrolled patients were followed-up from time of enrollment till the day of discharge or demise and evaluated by: Demographic data, full history including, complete physical examination, radiological investigations to identify the source of sepsis, all routine laboratory investigations and sepsis workup and all possible microbiological cultures prior to antibiotic administration or after discontinuation of antibiotic for 48 hrs. APACHE II score (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) was evaluated on study day 1. SOFA score (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment) was evaluated on study day 1 and serially every day until ICU discharge or demise. RIFLE criteria was evaluated daily. The primary outcomes were the need for organ supportive measures (vasopressor, mechanical ventilation MV and/or renal replacement therapy RRT) and length of ICU stays. The secondary outcome was in-ICU mortality.

Results

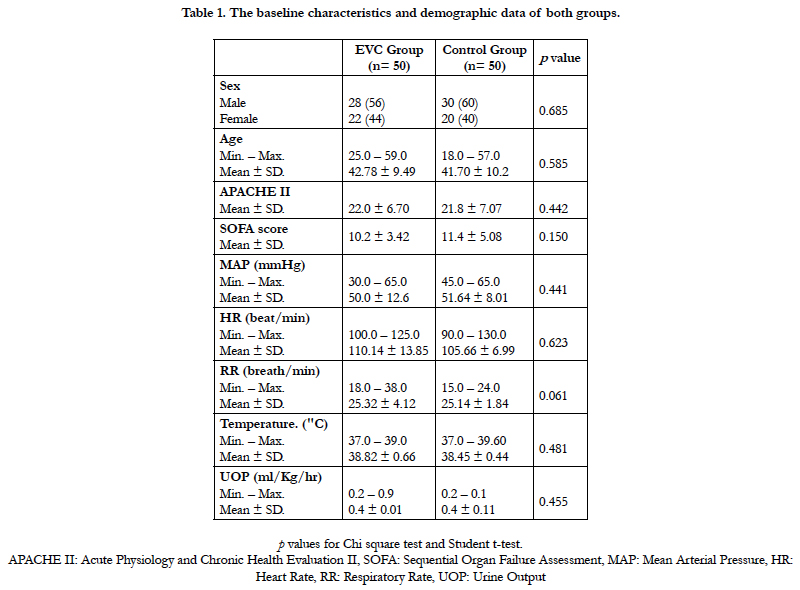

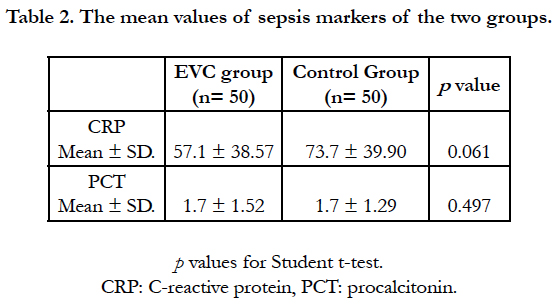

The baseline characteristics and demographic data of both groups showed no differences regarding age, gender, APACHE II, SOFA score and vital signs at admission (Table 1). There was no significant difference between the two groups in source of sepsis (p=0.088) Chest infections was the most common source of sepsis in both groups. Other identified sources were abdomen, soft tissue, urinary tract infections and central nervous system infection respectively. Most of cultures showed gram negative organisms in both groups with no difference between them (p=0.551). The values of sepsis markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT) were elevated above normal ranges in both groups with no differences between them (p=0.061, 0.497 respectively) (Table 2).

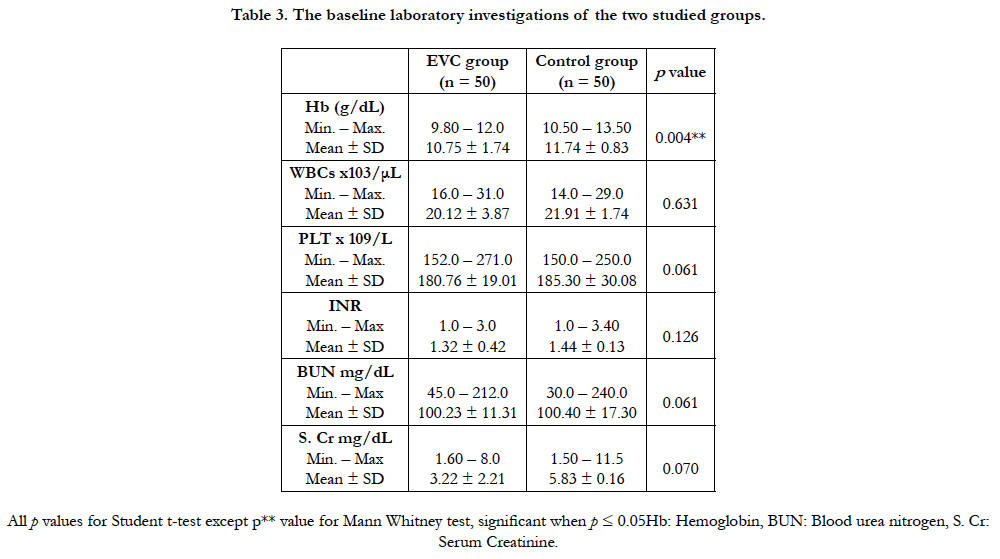

All data about laboratory investigations at admission of all patients showed no significant differences in white blood cells count (WBCs), platelets count (PLT), coagulation profile, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (S. Cr). The mean hemoglobin level (Hb) showed a statistically significant difference in favor or the control group (11.74 Vs 10.75, p=0.004) for the control and EVC group respectively (Table 3).

Regarding this study main outcomes, results showed no differences between the two groups in duration on MV. The mean number of days of MV in EVC group was 4.60 while, it was 7.87 in control group but without significance (p=0.187). The mean number of days on vasopressor was significantly less in EVC group than in control group (2.30 Vs 6.50 days, p=0.001). There was a statistically significant difference in ICU stay between the two groups (p=0.04). the mean number of days of ICU stay in EVC group was 10 while, it was 14.10 in control group. There were no any significant differences in need for RRT or ICU mortality (p=0.412, p=0.138 respectively) (Table 4).

Discussion

There are few studies on the effect of vitamin C in critically ill patients. Also, the outcome of these studies are difficult to interpret due to heterogeneous patient populations are included, different and mostly low doses of vitamin C are used, mixed oral and intravenous doses, and other antioxidants agents are often associated. Most experience with adjuvant vitamin C has been obtained in cases of severe burn injury [6]. Using high doses of vitamin C to standard fluid resuscitation showed a significant reduction in fluid requirements and net fluid balance in an animal burn model [8]. Two small studies in burn patients assessed the high-dose vitamin C as continuous infusion within the first day after thermal injury. One prospective study randomized patients to receive their fluid resuscitation alone or with vitamin C. Vitamin C treatment showed a reduction in resuscitation volume and resulted in better gas exchange and less days on mechanical ventilation [9]. A recent retrospective study confirmed these findings and also reported an increase in urinary output UOP in vitamin C group of patients [10]. But similar to this study findings there were no any benefit in mortality in those previous two studies.

In animal studies, intravenous vitamin C showed a rapidly and persistently improved capillary and microcirculatory blood flow, decreased microvascular permeability, and reduced inflammation [6]. Also, it restored endothelial barrier function, prevented apoptosis, and exerted antimicrobial effects [11]. Vitamin C may diminishes exogenous vasopressor need in septic shock as it acts as a cofactor to optimize activity of the enzyme dopamine β-hydroxylase which synthesize norepinephrine [12]. This was similar to this study results as vitamin C showed a reduced duration on vasopressor in EVC group.

In accordance with this study results, Fowler et al., in 2014 studied the infusion of 50 or 200 mg/kg/day vitamin C (ascorbic acid) every six hours for four days in patients with severe sepsis. They compared it with placebo, vitamin C showed less inflammation and reduction of organ failure [13]. Zabet et al., in 2011 also compared infusion of 25 mg/kg vitamin C every six hours for three days with placebo in patients with septic shock who required vasopressor (NE). Their results showed that the duration of NE infusion were significantly lower in vitamin C group [14]. But, vitamin C group showed lower 28-day mortality unlike this study results.

Hyperoxaluria and formation of stones in the kidneys is a potential adverse effect associated with high doses of vitamin C administration [15]. But, there were no any complications related to the high dose of vitamin C in EVC group studied in this trial. The same experience was found in the previous 2 studies. It was well tolerated and devoid of adverse effects. Under normal physiological conditions, 100-300 mg vitamin C per day is sufficient enough to reach adequate plasma concentration [16]. but, critically ill patients may need up to 3 g daily to restore normal plasma concentrations [17]. The high dose of vitamin C infusion resulted in a 20-500 % increase in its plasma concentrations [9, 13]. Also, it is not known whether sepsis patients with normal to slightly decreased vitamin C plasma concentrations may benefit from high doses.

Conclusion

Early adjuvant high dose intravenous vitamin C (ascorbic acid) treatment in patients with septic shock may resolve the vasopressor-dependent septic shock rapidly and decrease their ICU stay with no benefit on mortality. Additional studies are required to confirm these preliminary findings, the most effective dose and time for administration remain to be determined. Limitations of this study were that there was no baseline for vitamin C concentration obtained in all patients and there was no vitamin C dose modification considered for patients on RRT. Further studies should consider the dose of vasopressor used not only duration on vasopressor.

References

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Angus DC, et al., (2016) The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). Jama. 315(8): 801-10.

- Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, Rea TD, Kahn JM, et al., (2016) Assessment of Clinical Criteria for Sepsis: For the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). Jama. 315(8): 762-74.

- Seymour CW, Deutschman CS, Levy M, Rhee C, Warren DK, et al., (2016) Application of a Framework to Assess the Usefulness of Alternative Sepsis Criteria. Crit Care Med. 44(3): e122-30.

- Carr AC, Shaw GM, Fowler AA, Natarajan R (2015) Ascorbate-dependent vasopressor synthesis: a rationale for vitamin C administration in severe sepsis and septic shock? Crit Care. 19: 418.

- Vitamin C: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals, 2017.

- Oudemans-van Straaten HM, AM Spoelstra-de Man, MC de Waard (2014) Vitamin C revisited. Crit Care. 18(4): 460.

- Borrelli E, Roux-Lombard P, Grau GE, Girardin E, Dayer J, et al., (1996) Plasma concentrations of cytokines, their soluble receptors, and antioxidant vitamins can predict the development of multiple organ failure in patients at risk. Crit Care Med. 24(3): 392-7.

- Dubick MA, Williams C, Elqio GL, Kramer GC (2005) High-dose vitamin C infusion reduces fluid requirements in the resuscitation of burn-injured sheep. Shock. 24(2): 139-44.

- Tanaka H, Matsuda T, Miyaqantani Y, Yukioka T, Matsuda H, et al., (2000) Reduction of resuscitation fluid volumes in severely burned patients using ascorbic acid administration: a randomized, prospective study. Arch Surg. 135(3): 326-31.

- Kahn SA, RJ Beers, CW Lentz (2011) Resuscitation after severe burn injury using high-dose ascorbic acid: a retrospective review. J Burn Care Res. 32(1): 110-7.

- Wilson JX (2013) Evaluation of vitamin C for adjuvant sepsis therapy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 19(17): 2129-40.

- Levine M (1986) Ascorbic acid specifically enhances dopamine beta-monooxygenase activity in resting and stimulated chromaffin cells. J Biol Chem. 261(16): 7347-56.

- Fowler AA, Syed AA, Larus T, Martin E, Brophy D, et al., (2014) Phase I safety trial of intravenous ascorbic acid in patients with severe sepsis. J Transl Med. 12: 32.

- Zabet MH, Mohammadi M, Ramezani M, Khalili H (2016) Effect of highdose Ascorbic acid on vasopressor's requirement in septic shock. J Res Pharm Pract. 5(2): 94-100.

- Thomas LD, Elinder CG, Tiselius HG, Wolk A, Akesson A, et al., (2013) Ascorbic acid supplements and kidney stone incidence among men: a prospective study. JAMA Intern Med. 173(5): 386-8.

- Levine M, SJ Padayatty, MG Espey (2011) Vitamin C: a concentrationfunction approach yields pharmacology and therapeutic discoveries. Adv Nutr. 2(2): 78-88.

- Long CL, Maull KI, Krishnan RS, Laws HL, Franks W, et al., (2003) Ascorbic acid dynamics in the seriously ill and injured. J Surg Res. 109(2): 144-8.