Veterinary Expert Opinions on Conflicts Involving Dogs and Cats in Poland

Babińska I1, Kusiak D1, Szarek J1, Lis A1, Gulda D2, Felsmann MZ3*, Łyko A1, Maciejewska M1, Popławski K1, Szweda M1

1 Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Pathophysiology, Forensic Veterinary Medicine and Administration, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Poland.

2 Faculty Of Animal Breeding And Biology Department of Sheep, Goat and Fur Bearing Animal Breeding,University of Science and Technology, Kordeckiego, Bydgoszcz, Poland.

3 Centre for Veterinary Sciences at the NCU, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Gagarina, Toruń, Poland.

*Corresponding Author

Mariusz Felsmann,

Centre for Veterinary Sciences at the NCU,

Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń,

Gagarina 11, 87-100 Toruń, Poland.

Email: felsmann.mariusz@wp.pl

Received: April 21, 2017; Accepted: June 05, 2017; Published: June 06, 2017

Citation: Babińska I, Kusiak D, Szarek J, Lis A, Felsmann MZ, et al., (2017) Veterinary Expert Opinions on Conflicts Involving Dogs and Cats in Poland. Int J Forensic Sci Pathol. 5(3), 347-351. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2332-287X-1700076

Copyright: Felsmann MZ© 2017. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Veterinary experts witnesses issue opinions contributing to improved detectability of crimes in which cats and dogs are victims. The aim of this study was to analyse veterinary expert opinions on conflict situations concerning cats and dogs in regard to the types of entities which commissioned such opinions, the structure of entities liable to criminal proceedings, the reasons for which criminal proceedings were initiated and the experts’ conclusions. Proceedings were initiated by law enforcement bodies mainly because of violations of the animal protection act; law enforcement bodies accounted for the majority of the entities commissioning such opinions. Smaller numbers of opinions were commissioned by individuals and single opinions were commissioned by an underwriter for professional liability, civil courts, insurance agencies and animal welfare associations. Criminal proceedings were usually initiated against individuals and veterinary surgeons. Cruelty to dogs and cats were found to be the main cause of conflict situations. Veterinary malpractice or a fraud in sale/purchase transactions were identified as the cause in a smaller percentage of cases. The autopsies of cats and dogs performed for such opinions showed that the deaths had been caused mainly by physical injuries and cardiopulmonary insufficiency. The division of the investigated period into two decades demonstrated that in 2006-2015, as compared with the data recorded in the previous decade, there was a statistically significant increase in the number of animal deaths due to hitting/beating and shooting and a decrease in fatal cases resulting from cardio-respiratory failure, poisoning and infectious diseases.

2.Introduction

3.Material and Experimental Methods

4.Results and Discussion

5.Acknowledgement

6.References

Keywords

Dogs; Cats; Criminal Case; Veterinary Experts Opinion; Attitude to Pets.

Introduction

The obligation to treat animals humanely has developed along with civilisation [1, 3, 6, 7, 18]. The growth in people’s awareness of animal rights, especially those of house pets, has resulted in reporting violations of animal rights [4, 9, 14, 19]. Because of their specific nature and the need for an in-depth analysis of facts, such cases require the involvement of a veterinary expert [2, 13, 14, 16]. The decision to appoint an expert witness helps to sharpen the questions to which a witness answers in their testimony. In such cases, the outcome of their work is regarded as equal to other evidence and can be freely assessed by a law enforcement body [5, 8, 13].

As a response to the need for expert witnesses, forensic veterinary medicine has emerged and developed. This interdisciplinary branch of veterinary medicine can be used to employ a comprehensive approach to examining circumstances of conflicts with animals as their victims. Propagating this knowledge can boost its growth and development, benefiting expert witnesses and law enforcement bodies, but also practicing veterinary surgeons [8, 13, 14, 19]. Therefore, the aim of this study is to analyse opinions on conflict situations related to cats and dogs, issued over a period of 20 years by the Unit of Forensic Veterinary Medicine (UFVM) at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn (Poland).

Material and Experimental Methods

The study material included 79 opinions on conflicts, including 70 on those regarding dogs and 9 on those regarding cats, issued in 1995-2015 by the UFVM for employers from all over Poland. Since the dynamism of changes in conflict-generating potential was included in the analysis of the factors under study, two groups of opinions were identified: 1. – issued between 1995 and 2005 – 26 opinions, 2. - issued between 2006 and 2015 – 53 opinions. For all variables, the percentage proportions of causes of animal deaths were determined and for comparative purposes, statistical differences were calculated with the chi2 test for the investigated characteristics in the two specified time sections. The calculations were performed with the Statistica 9PL StatSoft software package [11].

Results and Discussion

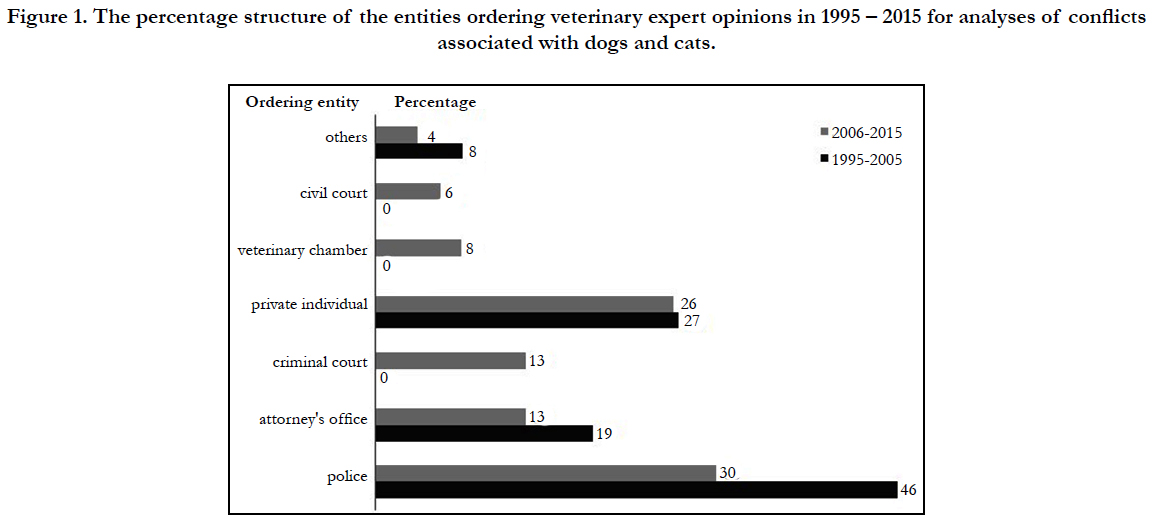

The 79 opinions issued over the period of 20 years were commissioned by different entities [Figure. 1]. The majority of them (47) were commissioned by law enforcement bodies, i.e. police, attorneys and a criminal court. By individuals were commissioned 21 opinions. Courts other than criminal courts commissioned seven opinions, including four for courts at the veterinary chambers, and three for civil courts. In the two cases, opinions were commissioned by insurance agencies and in another two by animal welfare associations.

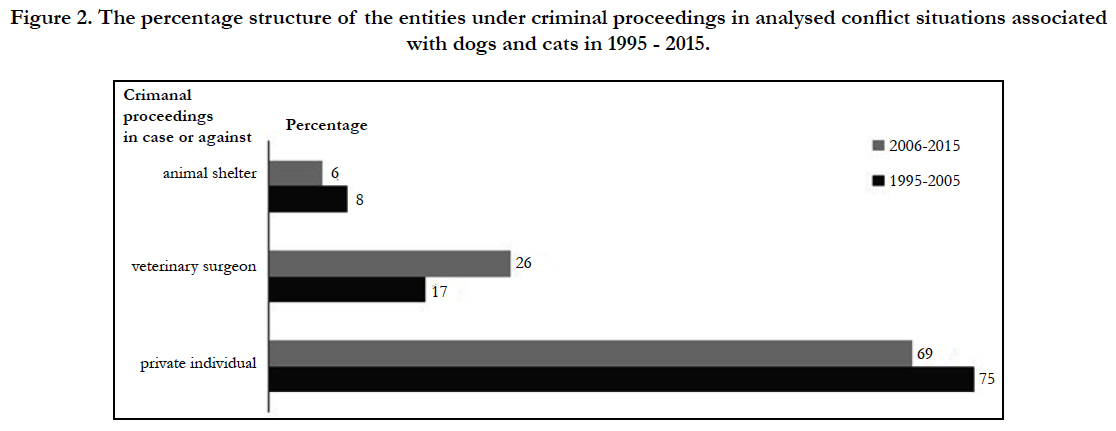

Opinions issued in criminal proceedings concerned individuals, veterinary surgeons and animal shelters [Figure. 2]. The majority of these entities were individuals (70.21%) and veterinary surgeons (23.4%).

Figure 1. The percentage structure of the entities ordering veterinary expert opinions in 1995 – 2015 for analyses of conflicts associated with dogs and cats.

Figure 2. The percentage structure of the entities under criminal proceedings in analysed conflict situations associated with dogs and cats in 1995 - 2015.

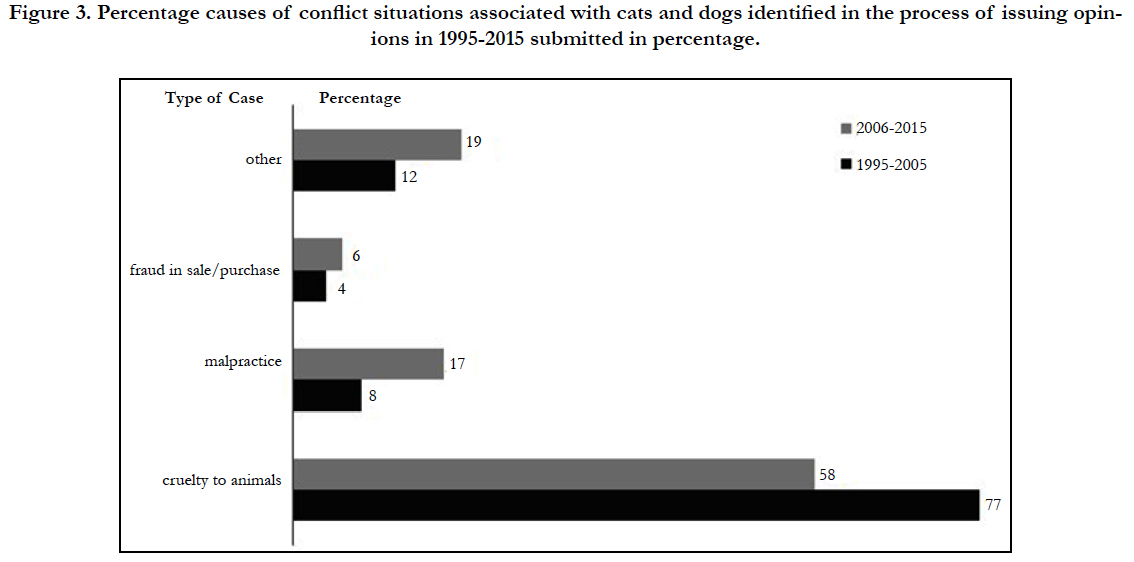

Following an analysis of the causes of conflicts regarding cats and dogs, it was concluded in the opinions that in 64.56% of the cases under analysis (51 cases), animal abuse lay at the root of the conflict [Figure. 3]. This category was dominated by unjustified and inhumane killing of animals (40 cases). It was found in 25 cases that an animal had died because of an injury, in five - because of poisoning, and in four due to drowning/strangling. The most frequent physical injuries included hitting/beating (16 cases) and gunshot wounds (eight cases). In one case, the death was caused by stab wounds. The shots were fired by hunters in five cases, by a policeman and by a sheep breeder in the other two. However, in one case, the person who shot and killed a cat with an air gun could not be identified.

Figure 3. Percentage causes of conflict situations associated with cats and dogs identified in the process of issuing opinions in 1995-2015 submitted in percentage.

The autopsies in cases of animal poisoning usually indicated the contact of the pets with anticoagulant rodenticides [16]. In one case, two Doberman dogs were poisoned as a result of a quarrel between neighbours. In one case, anatomopathological symptoms of poisoning with anticoagulant rodenticides were demonstrated in a female cat and her offspring. Characteristic cereal grain was found in the stomach of one dog, which also indicated that it had eaten a rodenticide. However, since no toxicological tests were carried out, poisoning with anticoagulant rodenticides was only suggested as the most probable, but not the definite, cause of death.

For drowned animals, there was one dog found largely decomposed in a well and one fished out of a lake. It was demonstrated in one case that the animal had been strangled by clogging/crushing the upper airways. And in the other case of inhumane killing of a dog, the post mortem examination revealed that the animal had been buried alive.

There were also other, isolated cases of cruelty to animals. It was shown in three of them that dogs had died due to prolonged starvation. In one case, the dog had died because of the clogging of its stomach with pieces of material soaked with blood (this is how dogs trained to fight are “fed”) and resulted in shock and death. An inhumane killing was adjudicated in a case in which a puppy was thrown out of a window. Cases of cruelty to animals also included a lack of veterinary care of a left dog after it was hit by a car. In another case, the beating of a dog and the owner’s negligence was demonstrated which involved failure to provide treatment for a dog with a pelvic limb injury. In one case, police commissioned a clinical examination of a dog. The owner reported that the dog had been shot at with an air gun. An X-ray image revealed the presence of three pellets in the dog’s body. In one opinion, which was related to incorrect transport conditions, the post mortem revealed patent ductus arteriosus as the cause of a puppy’s death. In another two, suspected cruelty to animals as the cause of the death was not confirmed in the post mortem. However, anaphylactic shock was identified as well as in case of a dog which was bitten by another animal, most probably by another dog(s). Cruelty to animals sometimes encompasses inflicting keeping animals in adverse conditions. There were five such cases. Defects found most frequently included a lack of protection against adverse weather conditions, insufficient area provided to animals, sick animals not isolated from healthy ones. It was also found in one case that extreme aggressiveness of dogs in an animal shelter was indicated as the cause of 40% of cases of euthanasia. Another two cases were against owners who left their animals uncared for over a long period.

An analysis of the opinions issued during the 20 years of service of the UFVM revealed that the number of cases against veterinary surgeons increased. Two such cases were recorded during the first period. One of them concerned two ragdoll cats with infectious peritonitis FIP. This opinion was commissioned by an insurance agency and the proceedings concerned medical malpractice, which involved a wrong diagnosis and exposure of the animals to suffering. In another case, the actions of a veterinary surgeon as requested by the dog’s owner were analysed. Due to the ineffective treatment, the animal was referred to a diagnostic laparotomy and died shortly after it was performed. Nine such cases were recorded among the opinions which constituted the other study group. All of the cases were related to medical malpractice and the majority of them concerned negligence in surgery procedures [15]. An allegation of inefficacy related to a wrong diagnosis was levelled only in one case of a dog with the hip joint dysplasia. In one of the cases in a civil court for a compensation to a dog owner, inter alia, for lost income due to covering, a dressing was put on incorrectly after a tumour was removed (result - necrosis and amputation), in effect, it was no longer useful as a reproducer. It was established in one case that the dog’s death was caused by an anaphylactic shock following administration of drugs, probably penicillin. In the next four cases, the medical malpractice was related to a surgical procedure. In two cases, castration of a male and sterilisation of a female resulted in a haemorrhage which was not diagnosed and no proper treatment was implemented. It was established in two cases that the death of an animal had been caused by a cardiogenic shock/cardiopulmonary insufficiency following administration of anaesthetic drugs. No medical malpractice was confirmed in three of the cases. A veterinary surgeon was accused of improper handling of a caesarean section, resulted in the death of the bitch. Both the opinion and the initial proceedings proved that the procedure had been performed correctly, and the death of the dog had been caused by a toxic shock. No veterinary malpractice was also found in a similar case in which aid was provided in a delivery. It was found in another case that the actions taken by a veterinary surgeon did not contribute to intestine perforation in pancreatitis in a dog, which was properly diagnosed and treated.

Conflicts also arose out of sale/purchase transactions [10, 16]. Physical defects were found in dogs in 2 cases. A disease of the urinary-reproductive system in a bitch and hip joint dysplasia in a (male) dog prevented the use of the animals for reproduction. Another two cases concerned puppies. It was shown in one of them that parvovirose had been caused by wrong prophylactic measures implemented by the new owner. The post mortem performed in the other case showed that the death of the puppy had been caused by gastric torsion.

Individual cases in which opinions were issued concerned different conflict situations associated with animals. In one case, the experts identified a lost dog based on the evidence. In second case a court asked the experts whether human DNA could be isolated from faeces of dogs suspected of biting a man to death. In the next two cases, the experts identified animal hair. In one of them, the hair of a dog was compared to that found on the fence surrounding a property, which turned out to be hair of a fox. In the other, it was established that the hair found at the site of a collision was dog’s hair. In one case, a question was asked whether the damage to a car had been caused by an accident with a cat.

One opinion was issued by a veterinary technician who performed a surgery in violation of his licence. His actions resulted in extending the period of healing of a post-surgery wound, thereby increasing the animal’s suffering.

The majority of the opinions (ca. 81%) entailed the need for an autopsy. This included 66 cases, of which 60 referred to dogs and 6 to cats. The majority of the autopsies were performed as an act in proceedings (55). Anatomopathological examination followed by issuing a report was performed in 5 cases requested by law enforcement bodies and in 4 commissioned by animal owners. Probably because the causes of deaths were mostly associated with a disease (gastric torsion, cancer, chronic systemic disease) and premeditated actions aimed at killing the animals were not confirmed, the criminal proceedings were not continued.

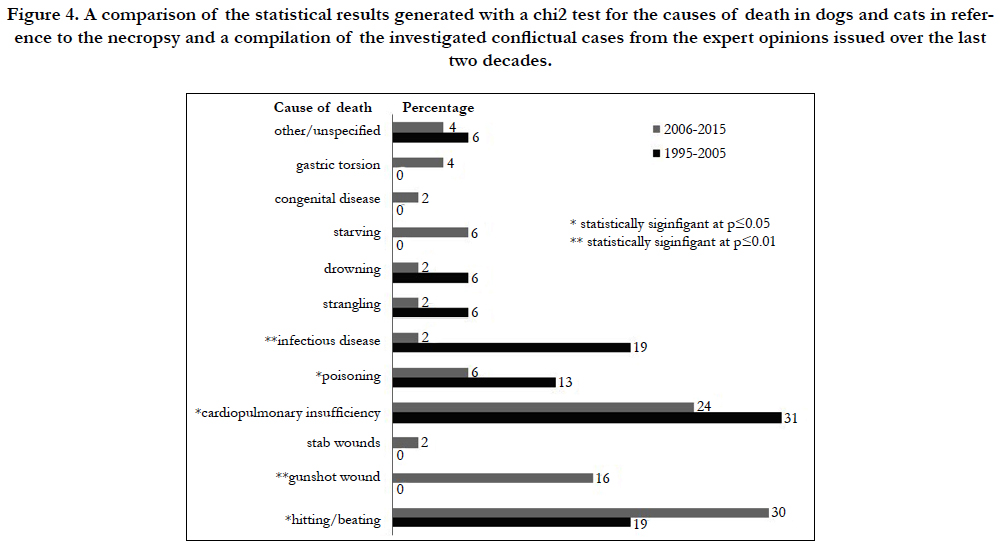

The autopsies found physical injuries as the most common causes of the animals’ deaths [Figure. 4], including 16 cases of hitting/ beating, eight cases of gunshot wounds and one stab wound. This was followed by cardiopulmonary insufficiency caused by an animal’s old age, various types of shock (including post-surgery complications) and chronic diseases (17 cases).

In five cases, it was assumed based on the autopsy changes that death had been caused by poisoning with rodenticides. Other causes of deaths included incurable infections (parvovirose) and invasive (babesiosis) diseases, strangling or drowning, prolonged starvation, congenital disease and gastric torsion. In three cases, autopsies were performed after exhumation of a corpse. The physical injury of the skull was identified as the cause of death in one case, a shock resulting from clogging the pylorus in another and strangling was identified in the third. It was impossible to identify the cause of death in three cases because of decomposition of the corpse. When determining the evidence-based cause of death (e.g. based on the enclosed autopsy protocol), it was found in two cases that the death had been caused by a physical injury.

Statistically analyzing the results of necropsy in two periods obtained in certain cases depending statistically significant [Figure 4]. It was found that from 2006 - 2015 the number of animal deaths resulting from hitting/beating and shooting increased, whereas the number of casualties due to cardio-respiratory failure, poisoning and infectious diseases decreased as compared to the 1995 - 2005 data.

Figure 4. A comparison of the statistical results generated with a chi2 test for the causes of death in dogs and cats in reference to the necropsy and a compilation of the investigated conflictual cases from the expert opinions issued over the last two decades.

An analysis of the opinions issued by the showed that the majority (59.5%) of expert opinions on conflicts associated with cats and dogs were commissioned by law enforcement bodies. Such opinions were commissioned by individuals relatively often (26.58%). Moreover, such opinions were commissioned - in separate cases - by veterinary chambers, civil courts and insurance agencies.

A comparison of the number of opinions issued during the period between 1995 and 2005 and between 2006 and 2015 showed that the number of opinions regarding dogs had increased in the later decade and it was greater by 57% than in the earlier decade. The most common reasons for seeking a veterinary expert opinion included: cruelty to animals, medical and veterinary malpractice and conflicts associated with sale/purchase transactions. In separate instances, those cases included accidents with animals, identification of a lost dog, establishing the species of an animal whose hair was found and the possibility of isolating human DNA from the faeces of dogs suspected of biting a man to death. In the majority of cases (81.01%), issuing an opinion was preceded by an autopsy. It was shown in these cases that physical injuries, cardiopulmonary insufficiency and poisoning were the most common death causes of dogs and cats. Furthermore, in the last period, compared to 1995 - 2005, there was a statistically significant increase in the number of animal deaths due to hitting/beating and shooting and a decrease in fatal cases resulting from cardio-respiratory failure, poisoning and infectious diseases. The results, combined with scarce literature data [2, 8, 12, 14, 19], suggest an increase in interest in the importance of forensic veterinary science in proceedings conducted by law enforcement bodies. Expert knowledge is increasingly often ussed to improve the detectability of crimes in which cats and dogs are victims [8, 12-14, 17]. An increase in the number of initiated criminal proceedings demonstrates not only a larger number of crimes committed, but also a greater awareness of the need for reporting such acts to law enforcement bodies. This is also confirmed by the fact that the number of proceedings concerning veterinary malpractice increased in the later of the decades under analysis.

Acknowledgement

Publication supported by KNOW (Leading National Research Centre) Scientific Consortium "Healthy Animal - Safe Food", decision of Ministry of Science and Higher Education No. 05-1/KNOW2/2015.

References

- Badam GL, Sankhyan AR (2009) Evolutionary trends in Narmada fossil fauna. Asian Perspectives on Human Evolution. Serials Publications, NewDelhi. 92–102.

- Barik SS, Sahani R, Prasad BVR, Endicott P, Metspalu M, et al., (2008) Detailed mtDNA Genotypes Permit a Reassessment of the Settlement and Population Structure of the Andaman Islands. Am J Phys Anthropol. 136(1): 19-27.

- Chandersekar C, Rao VR (2007) Genetic Finger Printing and Peopling of Indian sub-Continent. Human Origins, Genome & People of India: Genomic, Palaeontological & Archaeological Perspectives. Allied Publishers Pvt Ltd., New Delhi, 15-27.

- Chandrasekar A, Kumar S, Sreenath J, Sarkar BN, Urade BP, et al., (2009) Updating phylogeny of Mitochondrial DNA Macrohaplogroup M in India: Dispersal of Modern Humans in South Asian Corridor. PLoS ONE. 4(10): 1-12.

- Cameron D, Patnaik R, Sahni A (2004) The phylogenetic significance of the Middle Pleistocene Narmada hominin cranium from Central India. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 14(6): 419–447.

- Jungers WL, Grabowski M, Hatala KG, Richmond BG (2016) The evolution of body size and shape in the human career. Phil Trans R Soc B. 371(1698): 20150247.

- Kantha L, Kulkarni R (2014) Estimation of total length of humerus from its fragments in South Indian population. Original Article, Intl J Anat Res. 2(1): 213-20.

- Kennedy KAR (2000) God-Apes and Fossil men: The Paleoanthropology of South Asia. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

- Kennedy KAR (2007) The Narmada fossil hominid. Human Origins, Genome and People of India. New Delhi: Allied Publishers. 188-192.

- Kennedy KAR, Sonakia A, Chiment J, Verma KK (1991) Is the Narmada hominin an Indian Homo erectus? Am J Phys Anthropol. 86(4): 475 - 496.

- Kotlia BS, Joshi M (2008) Reconstruction of Late Pleistocene palaeoecology of the Upper Narmada valley (Central India) using fossil communities. Palaeoworld. 17(2): 153–159.

- Lumley MA, Sonakia A (1985) Premiere Découverte D‘un Homo erectus Sur Le Continent Indien a Hathnora, Dans la Moyennevallée de la Narmada. L’Anthropologie. 89(1): 13–61.

- Sankhyan AR (1997a) Fossil Clavicle of a middle Pleistocene hominid from the CentralNarmada Valley, India. J Hum Evol. 32(1): 3–16. doi:10.1006/ jhev.1996.0117.

- Sankhyan AR (1997b) A new human fossil find from the Central Narmada basin and its chronology. Curr Sci. 73(12): 1110–1111.

- Sankhyan AR (2005) New fossils of Early Stone Age man from Central Narmada Valley. Curr Sci. 88(5): 704–707.

- Sankhyan AR (2007) Significance of Human Post-cranial Fossils from Narmada with Remarkson the Skullcap. Human Origins, Genome and People of India. New Delhi: Allied Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 193-217.

- Sankhyan AR (2010) Pleistocene hominins and associated findings from Central Narmada Valley bearing on the evolution of man in South Asia. Panjab University, Chandigarh.

- Sankhyan AR (2013) The Emergence of Homo sapiens in South Asia: The Central Narmada Valley as Witness (Original scientific paper). Hum Biol Rev. 2(2): 136-152.

- Sankhyan AR (2015) Pleistocene hominin fossil discoveries in India: Implications for humanevolution in South Asia. Recent discoveries and perspectives in human evolution, BAR Intl Series 2719, England: Archaeopress. 41-51.

- Sankhyan AR (2016) Hominin fossil remains from the Narmada Valley. A Companion to South Asia in the Past. (1st Edn), New York: JohnWiley & Sons. 72-85.

- Sankhyan AR (2016) Indian Origins: Hominins & Their Cultures in Narmada Valley, Kolkata: Anthropological Survey of India, (Submitted).

- Sankhyan AR, Rao VR (2007) Did ancestors of the pygmy or hobbit ever live in Indianheartland? In: Indriati, E. (Ed.) Recent Advances on Southeast Asian Paleoanthropology and Archeology. GadjahMada University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. 76–89.

- Sankhyan AR, Sahani R (2015) The Andaman Pygmy: Origins and New Adaptations. Recent discoveries and perspectives in human evolution, BAR Intl Series 2719, England: Archaeopress. 161-171.

- Sankhyan AR, Badam GL, Dewangan LN, Chakraborty S, Prabha S, et al., (2012) New postcranial hominin fossils from the Central Narmada Valley, India. Advances in Anthropology. Sci Res. 2(3): 125-131. OI:10.4236/aa.2012.23015.

- Sankhyan AR, Dewangan LN, Chakraborty S, Prabha S, Kundu S, et al., (2012) New human fossils and associated findings from the Central Narmada. Curr Sci. 103(12): 1-9.

- Solan S, Kulkarni R (2013) Estimation of total length of femur from its fragments in South Indian Population. J Clin Diagn Res. 7(10): 2111-2115. DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/6275.3465.

- Sonakia A (1984) The skullcap of early man and associated mammalian fauna from Narmadavalley alluvium, Hoshangabad area, MP (India). Rec Geol Surv. India. 113: 159–172.

- Stewart TD (1951) Hrdlicka's Practical Anthropometry. (4th edn), The Wistar Institute of Anatomy & Biology, Philadelphia, 172.

- Trotter M, Gleser GC (1952) Estimation of stature from long bones of American Whites and Negros. Am J Phys Anthropol. 10(4): 463-514.

- VanHeteren AH, Sankhyan AR (2009) Hobbits and pygmies: trends in evolution. Asian perspectives on human evolution. New Delhi, Serials Publications. 172–187.