Early Childhood Caries And Its Associated Risk Factors In Tunisian Preschool Children: A Cross-Sectional Study

Yamina Elelmi*, Souha Cherni, Fatma Masmoudi, Ahlem Baaziz

Pediatric Dentistry Department, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Research Laboratory, Biological Approach and Dento facial Clinic LR12ES10 Monastir University, Monastir, Tunisia.

*Corresponding Author

Yamina Elelmi,

Pediatric Dentistry Department, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Research Laboratory, Biological Approach and Dento facial Clinic LR12ES10 Monastir University, Monastir, Tunisia.

E-mail: yamina_elelmi@yahoo.fr/yamina.elelmi@fmdm.u-monastir.tn

Received: March 14, 2024; Accepted: April 29, 2024; Published: May 17, 2024

Citation: Yamina Elelmi, Souha Cherni, Fatma Masmoudi, Ahlem Baaziz. Early Childhood Caries And Its Associated Risk Factors In Tunisian Preschool Children: A Cross-Sectional

Study. Int J Dentistry Oral Sci. 2024;11(1):5342-5348.

Copyright: Yamina Elelmi©2024. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Early Childhood Caries (ECC) is a severe form of decay that affects primary dentition in children. It has significant

impact on children's well-being.

Aim: The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of ECC and its associated risk factors among preschool children in

the region of Monastir, Tunisia.

Material and Methods: It was a descriptive cross-sectional study involving children in preschool establishments in Monastir,

Tunisia. An oral examination of 393 children was conducted and data collection through a questionnaire was completed by

parents. ANOVA test and Pearson chi-square test were used to determine the prevalence of ECC and its associated risk factors.

Results: The prevalence of ECC was 49.9% and the mean dmft index was 1.42+- 0.1. A statistically significant relationship

was found between the prevalence of ECC, the frequency of sweat consumption (p=0.05), the frequency of tooth brushing

(p=0.05),the mother’s level of education (p=0.05) and black stain (p=0.05).

Conclusion: The prevalence of ECC among preschool children was important. Prevention seems to be the best way to

reduce the prevalence of ECC. This involves educating parents about the importance of temporary dentition for an optimal

child development.

2.Case Report

3.Discussion

4.Conclusion

5.References

Keywords

Dental caries; Child; Preschool; Prevalence; Risk Factors.

Introduction

Early childhood caries is a serious internationally- recognized

public health problem because of its high prevalence, its early

appearance, its rapid progress, and its repercussions on teeth. It

greatly affects young children's well-being and it is difficult to be

treated.

It was thoroughly described for the first time in 1962 by Dr Fass.

He called it “Nursing bottle mouth” as he noticed a significant

prevalence of caries among children who were fed by nocturnal

milk bottles.[1]

This disease was initially associated with an inappropriate use of

the nursing bottle. Later, others terminologies were introduced,

such as “rampant caries” referring to a specific particularity of

this disease with regard to its more preferential progression on

smooth surfaces than on pits and cracks.[2]

In 2004, it was defined by the American Academy of Pediatric

Dentistry (AAPD) as the presence of one or more cavitated or

non-cavitated lesions, missing teeth (due to caries) or filled tooth

surfaces in any primary tooth in a child aged 71 months or younger.

[3]

The aetiology of ECC has been proved to be multifactorial, involving

cariogenic microorganisms, exposure to fermentable carbohydrates

through in appropriate feeding practices, and environmental

factors such as the socioeconomic status as well as the

parents’ education. [4]

The consequences of this pathology have an incidence on the child’s quality of life on both short-term and long-term basis in

the advanced cases. It can even have considerable economic and

social consequences for the child’s family.

Therefore, in order to identify the high-risk population at the earliest

stage, it is necessary to identify the risk factors of ECC.

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of ECC

among children under the age of six in the region of Monastir

and to analyze its risk factors.

Materials And Methods

It was a cross sectional study carried out in preschool establishments

in the region of Monastir, Tunisia. It included children

aged from 2 to 5 years with primary teeth.

Sample size

The required sample size was calculated according to the following

formula n= Z² x (P) (1-P)/d². [5]

where Z=1.96 is the confidence level for an accuracy of 0.05, p=

60.9% is the prevalence of early childhood caries according to

a similar epidemiological survey conducted in Morocco in 2013,

and d=0.05 corresponds to the chosen accuracy.

After this calculation, the sample size included at least 393 individuals.

The cluster sampling method was used for the selection of the

subjects.

A first draw was made to select 21 kindergartens in the various

places of the region holding children from all socioeconomic levels.

At the level of each cluster, a second draw was made to select

the eligible cluster units (small section, medium section, large section).

Inclusion Criteria

The children included in this study were:

- Those under 6 years of age who were present in the kindergarten

at the time of the study.

- Those with primary dentition.

- Those whose parents completed the questionnaire.

Non-inclusion criteria:

The children non-included in this study were:

- Those who were absent during our visit.

- Those with mixed dentition.

- Those whose parents did not consent to their children’s participation

or who did not complete the questionnaire.

The non-included children equally participated in the interactive

session to increase awareness of the oral health and dental hygiene

services.

Conduct of the study

First, an approval from the Regional delegation of the Ministry of

Family and Child Welfare was obtained. Then, the heads of the

kindergartens were informed about the study. Finally, consents of

the parents were obtained.

During the first visit, the questionnaires were given to the teachers

at these institutions who were asked to distribute them to the

children’s parents. They were given an average of one week to fill

in the required information. During the second visit, the questionnaires

were collected and an oral examination was performed.

Data collection

Data were collected using a questionnaire filled out by the parents

and an oral examination conducted by a single examiner.

The questionnaire included information regarding the parent’s

demographic data, educational level, origin, marital status, medical

coverage, and the duration as well as the type of breastfeeding.

Information about the child included the, general health state,

visits to the dentist, feeding habits during the day and night, duration

and content of the baby bottle and finally the oral hygiene.

Oral examinations were performed at kindergartens by a trained

dentist and were based on the WHO guidelines (WHO 1997, oral

health surveys: basic methods 4th edition). The Children were

seated on a chair facing a window and the examiner respected all

hygienic cautions, including wearing disposable gloves and tongue

droppers to prevent cross-infection between children. No radiographs

were taken.

The oral examinations recorded dmft indexes, including the number

of decayed, extracted, and filled primary teeth. The presence

of black stain was also recorded according to Koch method

which consists in visual inspection of dark dots (less than 0.5 mm

in diameter), forming linear discoloration parallel to the gingival

margin at the dental smooth surfaces of at least two different

teeth without cavitation of the enamel surface. [5]

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0 and Microsoft

Excel 2010 software.

Significance was considered for p\0.05.

Analysis of data distribution was carried out using the Kolomognou-

smirnov test.

When distributions were normal and variances were equal, the

results were expressed as their mean +/- the standard error of

the mean. ANOVA test and Pearson chi-square test were used to

compare the different variables.

Results

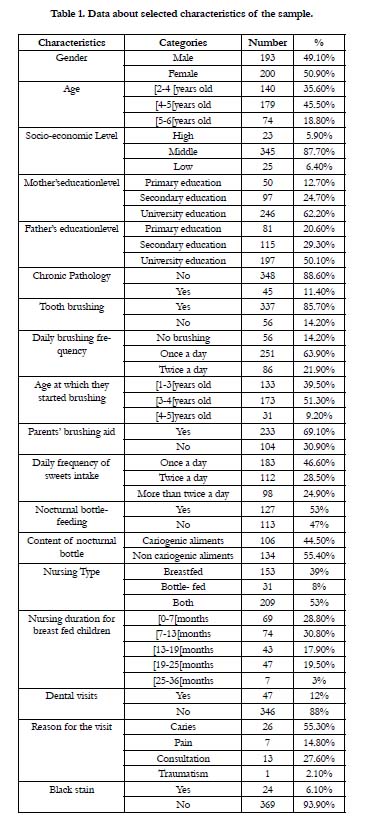

Table 1 shows the data of 393 included subjects (193 boys and

200 girls), according to the selected characteristics.

Of all the children, 45.5% were aged between 4 and 5 years and

87.7% came from a middle socioeconomic level.

A further examination of the parents’ academic statuses showed

that 62.2% of the mothers and 50.1% of the fathers reported

having a university level education.

Of all the children, 11.4% suffered from chronic pathology.

Concerning tooth brushing, 14.2% of the children did not

brush their teeth, 63.9% brushed their teeth once a day and

21.9%brushed their teeth twice a day.

Of all the children who brushed their teeth, only 39.5% started

brushing between the age of one and three, 69.1%were assisted

by their parents, and only 12% of them consulted a dentist with

dental caries as the main reason for the visit (55.5%).

Moreover, 39% of the children were breastfed for a long duration

(>-12 months),53% took nocturnal bottle, and 44.5% used cariogenic

aliments in the nocturnal bottle.

Almost 50% of the children took at least one sweet per day.Only

6.1% of the children presented black stain.

The prevalence of ECC was 49.9% (196/393) and the mean dmft

index was 1.42±0.1.

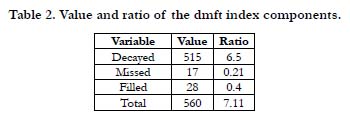

The different components of the dmft index are detailed in the

following table (table2).

With regard to the dmft index components, component “d” (decayed)

represented 90% of the dmft index. Actually, in this study,

515 decayed teeth were noticed while only 28 filled teeth and 17

missed teeth were present.

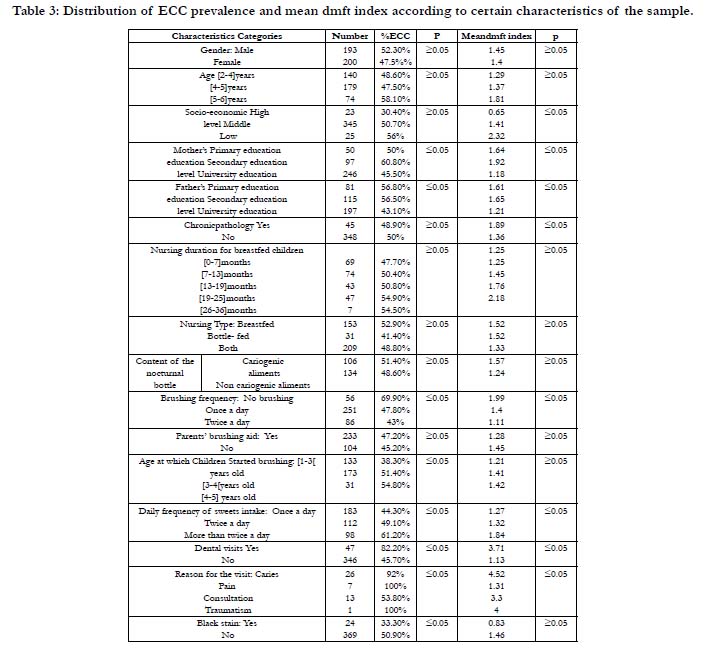

The distribution of caries prevalence and mean dmft index according

to certain characteristic of the sample are shown in table

3.

The highest prevalence of ECC was noticed in children belonging

to a low socio-economic level(56%), those who were breastfed

for prolonged duration(54.9%), those who did not brush their

teeth(69.9%), those who started brushing their teeth at the age

of three years(51.4%), and those who took sweets more than

twice per day (61.2%) .An increase in the dmft index with age was

found. It was 1.29 for children aged between 2 and 3 years, 1.37

for 4- year-old children and 1.81 for 5- year-old children.

No difference was noticed in the mean dmft indexes based on

gender. It gradually increased with age, though.

The mean dmft index was more important in children who suffered

from chronic pathology (1.89) than in those without chronic

pathology (1.36).

An incredible increase was noticed in the children who already visited a dentist with a value of 3.71. Those who consulted for

caries had the highest mean dmft index (4.52).The Subjects with

black stain(24) presented the lowest prevalence of ECC(33.3%)

and the lowest mean dmft index(0.83).

An association was found between ECC and the frequency of

tooth brushing, the daily frequency of sweets intake, the age at

which the children started brushing, the dental visits, the black

stain, and them others’ education level (p=0.05). Yet, no association

with the content of the baby bottle an the type of nursing

was found (p=0.05

With regard to the mean dmft index, a statistically significant correlation

was found with chronic pathologies, dental visits, reason

for visits, brushing frequency, sweets intake frequency, socio-economic

level and mothers’ education level (p=0.05).

Discussion

The results of this study revealed that caries prevalence in children’s

primary teeth was 49.9% and the mean dmft index was

1.42±0.1, which underlines a relatively important carious affection.

The prevalence of this disease varies from one country to another

and remains generally important in the developing countries.

Two studies in Saddar in Pakistan [7] and in Istanbul in Turkey [8]

showed similar prevalence to the one found in our study, being

close to 51%.

Some countries emerging as major world powers show inferior

prevalence than the one found in our study. For instance, in 2012

[9] the prevalence of caries in India was 27.5% with a mean dmft

index of 0.854 and in Brazil it was 20%. [10]

The most developed countries in the world show an inferior

prevalence compared to the one found in our study. We cite the

example of Brisbane in Australia, Singapore and the United States

with percentages of caries affection, respectively of 33.7%, 40%

and 28%. [11-13]

The observed differences with regard to ECC prevalence can be

explained by the economic conditions as well as the inequality

between the different countries and regions.

The lack of financial and human aptitude to promote oral health

among preschoolers in the emerging countries compared to the

developed countries, and the difficulty to access dental care in

some countries is the main reason for this difference.

The sample consisted of 393 children, including 193 boys. Similar

carious lesions were detected in both genders. No statistically

significant relationship was identified (p=0.05). This was substantiated

by many studies [7, 14] even though some other surveys

proved the opposite. [15]

The absence of correlation between these two parameters can be

due to the fact that kids at that age, regardless of their gender,

are not conscious of the importance of their oral hygiene habits

as they depend on their parents concerning brushing habits and

alimentation.

The results revealed an increase in carious affection with age. In

fact, the mean dmft index was 1.29 for children between 2 and 3

years, 1.37 for 4-year-old children and 1.81 for 5-year-old children.

Even though the statistical relationship in this study was not significant

(p=0.05), most of other studies confirmed this correlation.

[13, 7, 9]

To explain this association, time(being a major component of

Keyes modified scheme) becomes more considerable and teeth

become more and more exposed to oral environment.

Another plausible explanation is related to the alimentation habits.

These habits become uncontrolled with time, especially among

preschoolers.

There is also a lack of monitoring with respect to tooth brushing

that may affect the brushing quality and eventually the overall oral

hygiene quality.

It has been demonstrated in several studies [16] that an adequate

oral hygiene contributes to a decrease in caries. The current

study revealed a statistically significant relationship between daily

brushing frequency and ECC (p=0.05). In fact, children brushing

their teeth once a day presented an ECC prevalence of 47.8%

and a mean dmft index of 1.4 which is remarkably lower than

those found in children without brushing habits, who presented a

prevalence of 69.9% and a mean dmft index of 1.99.

Some urgent procedures should be taken in order to include systematic

correct teeth brushing techniques in preschool establishments.

[17]. Serious preventive approaches, such as awareness

campaigns and intervention programs, should also be introduced

to inform parents and raise public awareness regarding simple

practices to prevent early caries in children.

The statistical relationship between the age at which children

started brushing and ECC prevalence was significant (p=0.05).

The results showed an ECC prevalence of 38.3% for children

who started brushing between 1 and 2 years. However, children

who started after the age of 3 presented a higher prevalence of

ECC. The mean dmft index confirmed this main point as we

found a mean dmft index of 1.21 for the kids who started brushing

between 1 and 3 years and 1.4 for the others.

In view of what was previously mentioned, the time of the oral

cavity exposure to bacteria because of the lack or absence of oral

hygiene may increase the risk of ECC. Hence tooth brushing

should be performed for children twice daily and started as soon

as the first primary tooth erupted as recommended by the American

Association of Pediatric Dentistry [18].

Parents’ assistance in the brushing process helps to improve its efficiency.

This has been found in previous studies even though no

significant statistical relationship was retained in our study. In fact,

children supervised during brushing presented a mean dmft index

of 1.28 against an index of 1.45 for non-monitored children. This

association was evoked by some authors [19, 9] who explained it

by the lack of manual dexterity in children, which is essential for

an efficient elimination of bacterial plaque.

The American Association of Pediatric Dentistry recommended

a dental visit at the age of one year, then bi-annual visits to the

dentist for children. [3]

Nevertheless, 88% of the children in our sample never visited the

dentist. This highlights the lack of interest on the part of parents

towards their children’s oral health, especially with regard to primary

dentition.

In fact, for children having previous dental visits, ECC prevalence

was 82.2%, twice as much as the rest of the sample presenting a

prevalence of 45.7%.

The mean dmft index confirmed this association with a value of

3.71 for the kids with dental care visits and 1.13 for the others. In

this study, this relationship was statistically significant both for the

dmft index (p=0.05) and the ECC prevalence (p=0.05).These results

proved that chief complaints were essentially caries-related.

A more important mean dmft index of 1.89 was noticed in children

with chronic pathologies compared to healthy children

whose dmft index was 1.36. This relationship was statistically significant

(p=0.05).This could be explained by the frequent intake

of drugs rich of saccharine.

Beyond the existing disparities throughout the world, ECC prevalence

remains high due to the accessibility and the increasing consumption

of refined sugars because of the modern life style and

nutritional changes caused by globalization. [20, 21]

More than three quarters of the children included in the sample

consumed cariogenic snacks or sweets between meals. In our

study, a statistically significant relationship was found between

the frequency of sweet consumption and both ECC prevalence

(p=0.05) and the mean dmft index (p=0.05).

The results of this study revealed that the higher the frequency of

sweets consumption between meals was, the more important the

carious affection was.

As a matter of fact, children who consumed sweets once a day

presented an ECC prevalence of 44.3% and a mean dmft index

of 1.27. However, children who consumed sweets more than

twice a day presented a prevalence of 61.2% and a mean dmft

index of 1.84.

The latter finding could be explained by the fact that sweets contain

rich amounts of fermentable carbohydrates, required for the

constitution of acids that maintain oral PH at low levels, which

will initiate the demineralization of teeth surfaces and consequently

the cariogenic process.

Concerning the use of nocturnal bottle, our study did not show

any statistically significant relationship between this variable and

ECC prevalence (p=0.05).

Indeed, ECC prevalence in children fed with nocturnal bottle and

in others was similar. The same was found with the mean dmft

indexes.

Our results are inconsistent with those found in many international

studies [22, 7-9] confirming that bottle feeding, especially at

night, is a major risk factor for developing ECC.

These results could be explained by the fact that this pathology

is not related to only nocturnal bottle nursing. For this reason, its

appellation was revised and it is now called early childhood caries,

instead of baby bottle caries.

In this study, the parents were asked about the nursing type offered

to their children as well as the duration.No statistically

significant relationshipwas foundfor ECC prevalence and mean

dmft index.

This was confirmed by a study conducted in India that compared

ECC prevalence according to the nursing type during early childhood.

[9]

However, an increase in ECC prevalence and mean dmft index

was observed with the increase of the nursing period.

In fact, the kids who were nursed over a period of time not exceeding

6 months presented an ECC prevalence of 47.7% and a

mean dmft index of 1.25. These values increased gradually until

reaching a maximum value for the kids who were nursed more

than two years with an ECC prevalence of 54.5% and a mean

dmft index of 2.18.Hence,it remains mandatory to limit the number

of meals to 5 at most.

The socio-economic level is considered as a risk factor for ECC

according to many studies. [23, 24, 9]

An association was found between the socioeconomic level and

the mean dmft index (p=0.05) This index was weaker for the kids

belonging to a high socio-economic level with an index 0.65 and

it increased considerably for the kids from a modest background

with a value of 2.32.s

Children with a modest background presented an ECC prevalence

of 56%, twice more important than the ECC prevalence

recorded in children belonging to a high background with an ECC

prevalence of 30.4%.

A modest socioeconomic background was correlated with nonaccessibility

to health care systems for dental treatments, bad nutritional

habits, and the parents’ perception towards the importance

of oral health in children at the early age. [25]

The parents ‘education level, particularly the mothers’, is defined

in several studies as a confirme d risk factor for ECC. [26, 13, 21]

Our study confirmed this finding. In fact, a decrease in ECC prevalence

was identified in the children whose mothers had received

a university education, with a value of 45.5% compared to the

children whose mothers had only had a secondary education, with

a value estimated at 60.8%. This relation was statistically significant

for both ECC prevalence (p=0.05) and dmft index (p=0.05).

In fact, the higher the educational level of the mother is, the more

conscious she is of the oral hygiene importance and the more

careful she is about her kid’s diet, especially sweets intake.

The relationship was statistically significant concerning the fathers’

education level for both ECC prevalence and mean dmft index values. Our results showed that children whose fathers’ received

a university education had an ECC prevalence of 43.1%;

however, children whose fathers received a primary education had

an ECC prevalence of 56.8%.Yet, some other studies have not

proved this association [27].

A statistically significant relationship was found between ECC and

black stain (p=0.05). Children with black stain had lower prevalence

of ECC (33.3%) than those without black stain (50.9%).

A lower mean dmft index was also noted in children with black

stain (0.83) than in those without black stain (1.46). These results

are consistent with many studies suggesting that black stain has a

protective effect against early childhood caries [28, 29].

Conclusion

This study demonstrated significant statistical relationships between

ECC prevalence and different parameters, such as the

frequency of sweets intake, the brushing frequency, the parents’

education level and black stain.

Deciduous teeth are always neglected by parents because of their

temporary aspect.

It is at this level that supplementary efforts should be made by

health care authorities and dentists to raise parents’ awareness regarding

the importance the lacteal dentition, having a primordial

role in an optimal biological and behavioral development of the

child.

In preschool establishments, teaching children an adequate brushing

technique is the best way to prevent EEC. Moreover, further

studies are needed to elucidate the causal relationship between

black stain and ECC.

Data Availability

The data of the assessed parameters used to support the finding

of the present study are available from the corresponding author

upon request.

References

-

[1]. Fass EN. Is bottle feedi

ng of milk a factor in dental caries. J Dent Child. 1962 Mar;29(7):245-51. [2]. Curzon ME, Drummond BK. Case report–Rampant caries in an infant related to prolonged on-demand breast-feeding and a lacto-vegetarian diet. J Paediatr Dent. 1987;3:25-8.

[3]. AAPD. Perinatal and Infant Oral Health Care. Pediatr Dent. 2017; 39: 208- 212.

[4]. Tinanoff N, Baez RJ, Diaz Guillory C, Donly KJ, Feldens CA, McGrath C, et al. Early childhood caries epidemiology, aetiology, risk assessment, societal burden, management, education, and policy: Global perspective. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019 May;29(3):238-248. PubMed PMID: 31099128.

[5]. Kang M, Ragan BG, Park JH. Issues in outcomes research: an overview of randomization techniques for clinical trials. J Athl Train. 2008 Apr-Jun;43 (2):215-21. PubMed PMID: 18345348.

[6]. Koch MJ, Bove M, Schroff J, Perlea P, Garcia-Godoy F, Staehle HJ. Black stain and dental caries in schoolchildren in Potenza, Italy. ASDC journal of dentistry for children. 2001 Sep 1;68(5-6):353-5.

[7]. Narendar D , Nighat N, Nazeer K, Shahbano S, Navara T. Prevalence and factors related to dental caries among pre-school children of Saddar town, Karachi, Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2012; 12:59- 67.

[8]. MÜNEVVEROGLU AP, Koruyucu M, Seymen F. Risk factors for early childhood caries (ECC) in 2-5 years old children. Journal of Istanbul University Faculty of Dentistry. 2014;48(1):19-30.

[9]. Subramaniam P, Prashanth P. Prevalence of early childhood caries in 8-48 month old preschool children of Bangalore city, South India. Contemporary Clinical Dentistry. 2012 Jan 1;3(1):15-21.

[10]. dos Santos Junior VE, de Sousa RM, Oliveira MC, de Caldas Junior AF, Rosenblatt A. Early childhood caries and its relationship with perinatal, socioeconomic and nutritional risks: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2014 May 6;14:47 PubMed PMID: 24885697.

[11]. Hallett KB, O'Rourke PK. Dental caries experience of preschool children from the North Brisbane region. Aust Dent J. 2002 Dec;47(4):331-8. Pub- Med PMID: 12587770.

[12]. Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, Lewis BG, Barker LK, Thornton-Evans G, et al. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Vital Health Stat 11. 2007 Apr;(248):1-92. PubMed PMID: 17633507.

[13]. Gao XL, Hsu CY, Loh T, Koh D, Hwamg HB, Xu Y. Dental caries prevalence and distribution among preschoolers in Singapore. Community Dent Health. 2009 Mar;26(1):12-7. PubMed PMID: 19385434.

[14]. Mahejabeen R, Sudha P, Kulkarni SS, Anegundi R. Dental caries prevalence among preschool children of Hubli: Dharwad city. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2006 Mar;24(1):19-22. PubMed PMID: 16582526.

[15]. Sufia S, Chaudhry S, Izhar F, Syed A, Mirza BA, Khan AA. Dental caries experience in preschool children: is it related to a child's place of residence and family income? Oral Health Prev Dent. 2011;9(4):375-9. PubMed PMID: 22238736.

[16]. Declerck D, Leroy R, Martens L, Lesaffre E, Garcia-Zattera MJ, Vanden Broucke S, Debyser M, et al. Factors associated with prevalence and severity of caries experience in preschool children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008 Apr;36(2):168-78. PubMed PMID: 18333881.

[17]. Tang JM, Altman DS, Robertson DC, O'Sullivan DM, Douglass JM, Tinanoff N. Dental caries prevalence and treatment levels in Arizona preschool children. Public Health Rep. 1997 Jul-Aug;112(4):319-29; 330-1. PubMed PMID: 9258297.

[18]. Dentistry AAOP, Pediatrics AAO. Policy on Early Childhood Caries (ECC): classifications, consequences, and preventive strategies. Pediatric Dentistry. 2011;30(7 Suppl):31–33.

[19]. Ibrahim S, Nishimura M, Matsumura S, Rodis OM, Nishida A, Yamanaka K, Shimono T. A longitudinal study of early childhood caries risk, dental caries, and life style. Pediatric Dental Journal. 2009 Jan 1;19(2):174-80.

[20]. Paul TR. Dental health status and caries pattern of preschool children in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2003 Dec;24(12):1347-51. PubMed PMID: 14710282.

[21]. erera PJ, Abeyweera NT, Fernando MP, Warnakulasuriya TD, Ranathunga N. Prevalence of dental caries among a cohort of preschool children living in Gampaha district, Sri Lanka: a descriptive cross sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2012 Nov 13;12:49. PubMed PMID: 23148740.

[22]. Weinstein P, Smith WF, Fraser-Lee N, Shimono T, Tsubouchi J. Epidemiologic study of 19-month-old Edmonton, Alberta children: caries rates and risk factors. ASDC J Dent Child. 1996 Nov-Dec;63(6):426-33. PubMed PMID: 9017177.

[23]. Gillcrist JA, Brumley DE, Blackford JU. Community socioeconomic status and children's dental health. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001 Feb;132(2):216-22. PubMed PMID: 11217596.

[24]. Filstrup SL, Briskie D, da Fonseca M, Lawrence L, Wandera A, Inglehart MR. Early childhood caries and quality of life: child and parent perspectives. Pediatr Dent. 2003 Sep-Oct;25(5):431-40. PubMed PMID: 14649606. [25]. Reisine S, Douglass JM. Psychosocial and behavioral issues in early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26(1):32-44. PubMed PMID: 9671198.

[26]. Schroth RJ, Moffatt ME. Determinants of early childhood caries (ECC) in a rural Manitoba community: a pilot study. Pediatr Dent. 2005 Mar- Apr;27(2):114-20. PubMed PMID: 15926288.

[27]. Masumo R, Bardsen A, Mashoto K, Åstrøm AN. Prevalence and socio-behavioral influence of early childhood caries, ECC, and feeding habits among 6-36 months old children in Uganda and Tanzania. BMC Oral Health. 2012 Jul 26;12:24. PubMed PMID: 22834770.

[28]. Saba C, Solidani M, Berlutti F, Vestri A, Ottolenghi L, Polimeni A. Black stains in the mixed dentition: a PCR microbiological study of the etiopathogenic bacteria. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2006 Spring;30(3):219-24.PubMed PMID: 16683670.

[29]. Theilade J, Slots J, Fejerskov O. The ultrastructure of black stain on human primary teeth. Scand J Dent Res. 1973;81(7):528-32. PubMed PMID: 4129441.