Impact Of Oral Health Related Quality Of Life And Possible Role Of Self- Esteem In Orthodontic Patients: A Prospective Clinical Study

Prasad Mandava1*, Surendra Gangavarapu2, GowriSankar Singaraju3, Venkatesh Nettam4, Sindhu Chandrika P5, Aparna Palla6

1 Professor and Head, Orthodontics, Narayana Dental College and Hospital, Nellore, AP, India.

2 Postgraduate Student, Orthodontics, Narayana Dental College and Hospital, Nellore, AP, India.

3 Professor, Orthodontics, Narayana Dental College and Hospital, Nellore, AP, India.

4 Senior Lecturer, Orthodontics, Narayana Dental College and Hospital, Nellore, AP, India.

5 Assistant professor, Government Dental College and Hospital, Kadapa, Nellore, AP, India.

6 Professor, Orthodontics, college of dental sciences, Davangere, India.

*Corresponding Author

Dr. Mandava Prasad MDS, FPFA, FICD (U.S.A.),

Sr. Professor & Head, Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Narayana Dental College and Hospital, Chinthareddypalem, Nellore – 524002, Andhra Pradesh, India.

Tel: 09440976666

E-mail: mandavabruno9@gmail.com

Received: September 07, 2021; Accepted: November 28, 2021; Published: December 07, 2021

Citation: Prasad Mandava, Surendra Gangavarapu, GowriSankar Singaraju, Venkatesh Nettam, Sindhu Chandrika P, Aparna Palla. Impact Of Oral Health Related Quality Of Life And Possible Role Of Self- Esteem In Orthodontic Patients: A Prospective Clinical Study. Int J Dentistry Oral Sci. 2021;8(12):5185-5190. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2377-8075-210001040

Copyright: Dr. Mandava Prasad MDS, FPFA, FICD©2021. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

The study aimed to evaluate the relationship between oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) concerning Self- esteem reports in children before, during and after orthodontic treatment. This prospective clinical study included 139 patients between 11-16 years old (66 boys and 73 girls) and requested to complete the questionnaires before the start of treatment (T0), one year after the start of treatment(T1), and at two months retention follow up(T2). One –way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparisons between the pre, mid and post-treatment means of the study group and to study the significance of changes in parameters over time (for both OHRQoL and SE measures). Pairwise comparison between the individual groups was made'Post – hoc Scheffe test.' Spearman's rank-order correlation coefficient (?) was used to evaluate the association between the two ordinal variables. The level of significance was set at a p-value of 0.05 for all tests.The mean value for overall OHRQoL was increased at mid-treatment and decreased at post-treatment, which is significant (p<0.001). The mean value for overall Self- esteem was decreased at mid-treatment and post-treatment, which is also significant (p<0.001). Oral health-related quality of life increased after orthodontic treatment compared to mid-treatment but comparatively less than at pre-treatment, which is statistically significant. The impact on OHRQoL increases during and after orthodontic treatment, and the self-esteem was decreased during and after orthodontic treatment.

2.Introduction

3.Materials and Methods

3.Results

4.Discussion

5.Conclusion

5.References

Keywords

Child Perception Questionnaire; Oral Health-Related Quality Of Life; Orthodontic Treatment; Self-Esteem.

Introduction

The goal of orthodontic treatment is to improve the life of patients

by enhancing dental, jaw function and dentofacial aesthetics.

The modern health care paradigm has shifted towards the

quality of life in the last decade. The impact of oral health on the

quality of life is measured by endogenous, functional, social or

psychological determinants and is usually known in the literature

as OHRQoL – the oral health-related quality of life.

Quality of life can be determined as ‘a person’s sense of well-being,

which stems from satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the areas

of life that are important to him or her.[1] Oral health-related

quality of life (OHRQoL) is defined as the absence of negative

impacts of oral conditions on social life and a positive sense of

dentofacial self-confidence.[2] The concept of oral health-related

quality-of-life (OHRQoL) has become increasingly more important

in oral health practice and research. In orthodontics, with a

shift from a more traditional biomedical model towards a more

biopsychosocial model, the interest in oral health-related quality

of life (OHRQoL) also has increased considerably.[3]

Oral health-related quality of life is a multidimensional concept

that includes subjective evaluation of perceived physical, psychological

and social aspects of oral health and no single measure

has been developed that captures the concept completely. Both generic and disease-specific measures had been used to measure

health and oral health-related quality of life.[4, 5]

Self-esteem (S.E.) can be defined as ‘the perception of one’s own

ability to master or deal effectively with the environment and

is affected by the reactions of others towards an individual [6].

Self-concept is broad-ranging and relates to personal self-concept

(facts or one's own opinions about oneself), social self-concept

(one's perceptions about how one is regarded by others), and selfideals

(what or how one would like to be).[3]

A malocclusion does affect physical, social and psychological

functioning, which can be defined as ‘quality of life’.[6] OHRQoL

can help us understand the demand for orthodontic treatment

beyond clinical parameters and sheds stumble across the effects

of malocclusion on people's lives.[7] The literature proposes that

studies on OHRQoL concerning malocclusion have reported

higher levels of oral impact in patients with severe malocclusion

compared with a normal population and the treatment of severe

malocclusion reduced the reported oral impacts to the level of the

general population and significantly improved oral health-related

quality of life. [8, 9] Hassan and co-workers [7] also found an

impact of malocclusion on oral health-related quality of life of

young adults. Furthermore, the subjects with more severe malocclusion

and dentofacial deformities are more likely to report oral

impacts than those with milder malocclusion.[10]

The impact of malocclusion differs between genders and age

groups. Studies have indicated that females experience poorer

OHRQoL than males. This gender difference in malocclusion

perception could be because females pay more attention to their

appearance and refer to orthodontic clinics more often than

males [11]. In a study of Brazilian school children, those with low

S.E. were found to be more sensitive to the aesthetic effects of

malocclusion.[12] The relationship between normative measures

of malocclusion, S.E., and OHRQoL was investigated by Agou et

al [3] using OHRQoL outcomes in children seeking orthodontic

treatment and hypothesized that children with high S.E. would

have better OHRQoL than those with low S.E. Likewise, a study

of potential orthodontic patients in Nigeria found that children

with high S.E. most frequently did notexpress orthodontic concerns.[

13]

Various studies investigated the effect of psychological aspects

during orthodontic treatment between treated patients and untreated

control group.[14, 15] Seeing that an unattractive dentition

has been associated with teasing, bullyingand negative OHRQoL

impacts. Differences between treated and untreated subjects are

anticipated in light of studies emphasizing the importance of

dentofacial esthetics in daily social interactions. [16-18] Thusimproving

dental esthetics and, subsequently, psychological well-being

is frequently stated reasons for seeking orthodontic treatment

during childhood and adolescence. [1, 19]

A recent cross-sectional study at the baseline by De Baets et

al.[20] was performed to investigate whether a relationship exists

between orthodontic treatment need and OHRQoL and whether

this relationship is influenced by Self-esteem (S.E.).On the continuation

of a baseline study, Brosen et al. [6] conducted a follow-up

study to investigate the changes of OHRQoL and the influence

of Self-esteem during the mid-treatment phase, one year after the

start of orthodontic treatment and hypothesized that OHRQoL

deteriorates during orthodontic treatment: Further they stated

that self-esteem can be a protective factor in OHRQoL during

orthodontic treatment.

Although there has been extensive research concerning the topic

of OHRQoL, the focus of most research projects was children.

[6, 9, 20] Only a few prospective studies have been published concerning

the effect of a change in occlusion on the OHRQoL. To

our knowledge, there is no published research using C.P.Q and

SPPA on Indian patients. This has encouraged us to carry out this

study to obtain the baseline information for the Indian population.

Therefore the present study was made to explore the changes

of OHRQoL and the possible role of self-esteem in children

before, during and after the completion of orthodontic treatment.

The study was conducted to assess (a) the OHRQoL reports in

children before, during and after orthodontic treatment, (b) to

estimate the Self- esteem reports in children before, during and

after orthodontic treatment and (c) to compare and correlate the

association between OHRQoL and Self- esteem in children before,

during and after orthodontic treatment.

Materials And Methods

Study Design

The present prospective study wasapproved by the institutional

ethics committee, Narayana Dental College and Hospital, Nellore

(NDC/IECC/2014-15/070 dt.31/12/2014). Informed consent

was obtained from all participants or where appropriate one of

their parents or caretakers after explaining the procedure in English

or their native language.

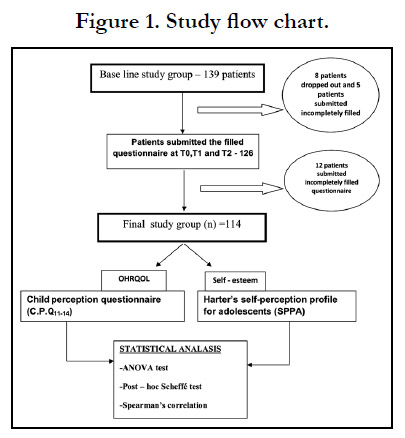

A total of 139 patients between 12-16 years old (66 boys and 73

girls) and requested to complete the questionnaire before the start

of treatment (T0). This study group was monitored throughout

the orthodontic treatment are requested to complete the same

questionnaire 3 months after the start of treatment (T1) and at

two months retention follow up (T2). Eight discontinued in between

treatment due to various reasons and five patients did not

turn up after two months retention follow up. So only 126 patients

were evaluated for the questionnaire given at three points

of time. Twelve patients submitted incompletely filled questionnaires

at one or the other point of time. This resulted in a final

study group of 114 patients (52 boys and 62 girls), who filled the

questionnaire at all three time periods required in this study. The

study flow chart describes the design of the study (Figure 1). Thus

the statistical analysis is done for this final study group (n=114).

The response rate is 82% which is sufficient for analyzing the

data.

Patients who had no history of previous orthodontic treatment,

with good physical and mental health and with fixed appliance

therapy were selected for this study. Subjects who exhibited severe

medical problems like mental and physical problems, children

with severe malocclusions like cleft lip andpalate, orthopedic

appliances, myofunctional and other removable appliances were

excluded from the study.

Every healthy child registered for first orthodontic treatment at

the Department of Orthodontics was requested to complete the same questionnaire format at three phases: pre-treatment, midtreatment

and post-treatment phases. The questionnaire at each

phase includes two sets of questions formulated to assess the

oral health-related quality of life reports and self-esteem of children

respectively. The pre-treatment score was considered as the

baseline of the present study. mid treatment questionnaire was

implemented three months after the start of the treatment and a

post-treatment questionnaire was implemented after treatment at

two months retention follow up.

The oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) of the child was

scored by using the original English or Telugu translation of the

child perception questionnaire (C.P.Q11-14) [21] has already been

validated in orthodontic research. It contains 37 questions about

the frequency of events at 4 domains.

Self-esteem of the child will be assessed by using the original English

or Telugu translation of the Harter’s self-perception profile

for adolescents (SPPA) [22], which consists of 35 questions designed

to discover the adolescent perception of themselves in 7

different domains. In line with our baseline study, ‘sense of dignity’

was considered as a measure of global Self- esteem.[23]

A detailed scoring key for this format was also provided in the

manual by S Harter [22]. Each of the seven subscales contains

five items, constituting a total of 35 items.

Statistical Analysis was performed using SPSS (Statistical Package

for the Social Sciences, version 21, Armonk, NY: I.B.M. Corp.).

Basic demographic data were expressed in means ± standard deviations.

The categorical data were converted to numerical scoring

and the Statistical test, ANOVA was used for comparisons between

the pre, mid and post-treatment means of the study group

and to study the significance of changes in parameters over time

(for both OHRQoL and S.E. measures). A pairwise comparison

between the individual groups was done ‘Post – hoc Scheffe test’.

Spearman's rank-order correlation coefficient (?) was used to

evaluate the association between the two ordinal variables. The

level of significance was set at p < 0.05 for all tests.

Results

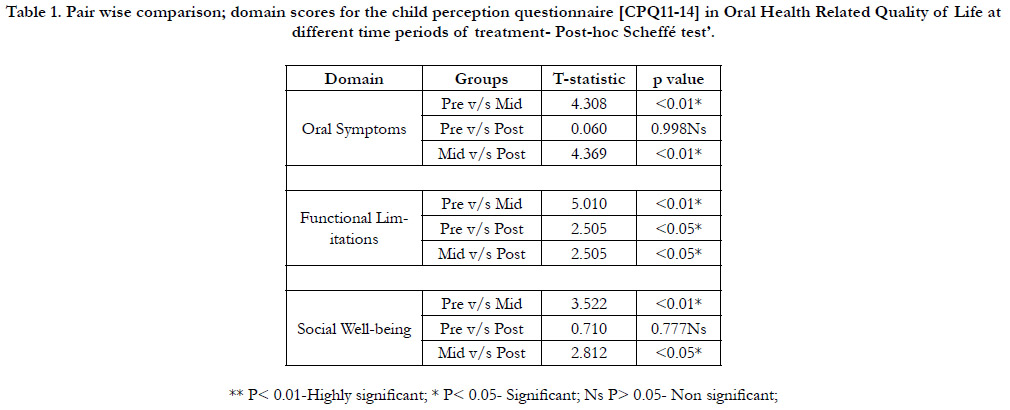

Table 1 shows the mean C.P.Q. scores for each domain were increased

at one year after starting treatment (T1) whereas scores

are decreased after treatment (T2). Post – hoc scheffe's test was

done for pairwise comparisons between pre (T0), mid (T1) and

post-treatment (T2) of significant domains of the "C.P.Q." questionnaire.

Table 2 shows the total 'C.P.Q.' and 'SPPA' scores for overall

OHRQoL and overall Self- esteem. The mean value for overall

OHRQoL was increased at mid-treatment and decreased at

post-treatment which is significant (p<0.001). The mean value

for overall Self- esteem was decreased at mid-treatment and posttreatment

which is also significant (p<0.001). Post-Hoc Scheffe's

test was done for multiple comparisons between pre (T0), mid

(T1) and post-treatment (T2) of overall "C.P.Q." and "SPPA"

scores (Table-3).

The correlation between the quality of life and Self- esteem at

pre (T0), mid (T1) and post-treatment time (T2) using spearman's

rank-order correlation coefficient (Table-4). The results showed

a weak negative correlation between total OHRQoL (C.P.Q.) and

S.E. at T0 (?=-0.167, p=0.075), T1 (?=-0.204, p=0.03) and positive

correlation at T2 (?=0.193, p=0.04).

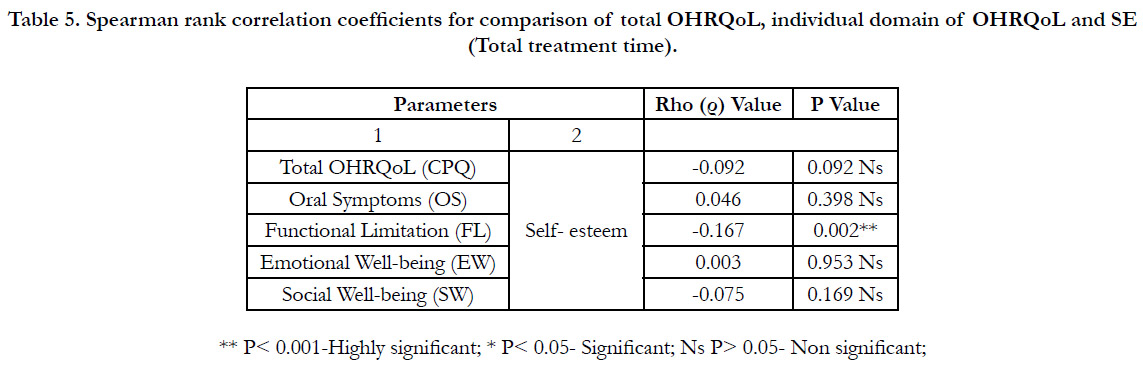

The correlation between the quality of life and Self- esteem was

assessed for total treatment time using spearman's rank-order

correlation coefficient. The results showed a weak negative correlation

between total OHRQOL (C.P.Q.) and S.E. (? = -0.092)

which is non-significant (p>0.05) (Table-5).

Table 1. Pair wise comparison; domain scores for the child perception questionnaire [CPQ11-14] in Oral Health Related Quality of Life at different time periods of treatment- Post-hoc Scheffé test’.

Table 2. Total scores for overall changes in oral health related quality (OHRQOL) of life and Self- esteem (SE) - “ANOVA” test.

Table 3. Pair wise comparison; overall OHRQOL and overall Self- Esteem measures at different time periods- ‘Post-hoc Scheffe test’.

Table 4. Spearman rank correlation coefficients for comparison of total OHRQoL, individual domain of OHRQoL and SE (At T0, T1, T2):

Table 5. Spearman rank correlation coefficients for comparison of total OHRQoL, individual domain of OHRQoL and SE (Total treatment time).

Discussion

The OHRQoL measure used in this study is the CPQ11-14. Because

of its definite psychometric properties, the CPQ11-14 is a

useful measure for orthodontic trials and has become a popular

tool in orthodontic outcome research [4, 24, 25]. The use of this

instrument is validated for the agegroup 11–14 years, but in our

study, we also included 15- to16-year-old subjects. Furthermore,

some authors question whether C.P.Q. is a good measure of

OHRQoL in children with malocclusions. Anyway, some criticism

of subjective measures suchas OHRQoL has to be taken into account:

people may adaptor habituate to their (health) conditions

over time and theymay respond with lower impact scores when

a questionnaireis re-administered at a later time[4,26]Bernabéet

al. [27] found a different pattern of sociodental impact by type

of appliance. Subjects wearing fixed appliances had a higher frequency

of impact than those wearing removable or both types of

appliances.

Finally, it is important to reconsider the current biomedical and

restricted paradigm on OHRQoL and to begin to think about

the series of processes by which social and psychological factors

influence OHRQoL reports [28]. According to the model of

Wilson – Clearly, also biological variables, health perception biological

variables, symptom status, healthy functioning, and other

(psychosocial) factors need to be taken into consideration [29].

In recent times, Baker and co-workers [30] demonstrated that

sense of coherence was the most important psychosocial predictor

for OHRQoL. For instance, the direct contribution of factors

such as other oral health problems was not assessed in this investigation.

A recent study by M.clijmans and co-workers [31] suggests

that orthodontic treatment need, S.E., and some personality traits

influence OHRQoL. Like the present study, a moderating role

cannot be confirmed.

Some limitations regarding this study also needed to be considered.

The results of the present study demonstrated the comparison

and correlation of OHRQoL and S.E. in the patients who had

come to the clinic and taken orthodontic treatment. The question

leftovers whether these correlations are still present in the general

population, and this aspect needs to be evaluated.

According to the literature, we expect that the OHRQoL will

change during treatment, but the association between OHRQoL

and S.E. depicts a weak correlation in the present study. The question

remains what the influence is of psychological factors such as

S.E. and personality traits, other psychosocial factors.

This study has not differentiated gender-wise comparisons; the

socioeconomic status of the subjects at baseline level was not

considered, and patients with only fixed appliances were found in

the present study.

Hence, further work should be attempted with larger samples,

different age groups, different gender, and longer follow-ups to

sort out the role of these factors on the outcome of orthodontic

treatment and the use of OHRQoL measures as validation for

orthodontic treatment. OHRQoL can provide evidence that costs

associated with treatment are worth the expense and can help the

patient in their decision making.Besides, professionals can weigh

the risks and benefits associated with treatment more accurately

[32].

Conclusion

• OHRQoL for total, oral symptoms, functional limitations, and

social well-being domains deteriorate during and after orthodontic

treatment.

• Total OHRQoL (for oral symptoms, functional limitations, and

social well-being domains) decreased during the mid-orthodontic

treatment compared to pre-treatment and then increased after

orthodontic treatment compared to mid-treatment but comparatively

less than at pre-treatment which is statistically significant.

• OHRQoL changes for oral symptoms, social well-being domains

were not evident when compared that at pre and post-treatment.

• Total S.E. also decreased during and after orthodontic treatment

when compared to that at pre-treatment.

• The correlation between OHRQoL and S.E. measured was

weak. However, as the impact on OHRQoL increases (high

C.P.Q. score) during and after orthodontic treatment, the S.E. was

decreased during and after orthodontic treatment.

Authors Contribution

Concept- Dr Prasad Mandava, Dr. SurendraGangavarapu, Design

– Dr. Prasad Mandava, DrGowriSankarSingaraju, Data Collection

and Processing- DrSurendraGanagavarapu, DrVenkateshNettam,

Analysis and Interpretation- Dr P. Sinduchandrika, DrSurendra-

Gangavarapu, Literature Search- Dr Aparna Palla, DrP.SinduChandrika,

Writing manuscript-Dr Mandava Prasad, DrGowriSankarSingaraju,

Critical Review- Dr Mandava Prasad, Dr Aparna

Palla

References

-

[1]. Cunningham SJ, Hunt NP. Quality of life and its importance in orthodontics.

J Orthod. 2001 Jun;28(2):152-8. PubMed PMID: 11395531.

[2]. Inglehart M, Bagramian R. Oral health-related quality of life. Chicago: Quintessence; 2002.1-6.

[3]. Agou S, Locker D, Streiner DL, Tompson B. Impact of self-esteem on the oral-health-related quality of life of children with malocclusion. Am J OrthodDentofacialOrthop. 2008 Oct;134(4):484-9. PubMed PMID: 18929265.

[4]. Locker D, Allen F. What do measures of 'oral health-related quality of life' measure? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007 Dec;35(6):401-11. Pub- Med PMID: 18039281.

[5]. Allen PF, McMillan AS, Walshaw D, Locker D. A comparison of the validity of generic- and disease-specific measures in the assessment of oral health-related quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1999 Oct;27(5):344-52. PubMed PMID: 10503795.

[6]. Brosens V, Ghijselings I, Jurgenlemiere, Steffenfieuws, Maiteclijmans, Willems G. Changes in oral health-related quality of life in children during orthodontics treatment and the influence of SE. Eur J Orthod. 2014; 36:186-91.

[7]. Hassan AH, Amin Hel-S. Association of orthodontic treatment needs and oral health-related quality of life in young adults. Am J OrthodDentofacial- Orthop. 2010 Jan;137(1):42-7. PubMed PMID: 20122429.

[8]. Rusanen J, Lahti S, Tolvanen M, Pirttiniemi P. Quality of life in patients with severe malocclusion before treatment. Eur J Orthod. 2010 Feb;32(1):43-8. PubMed PMID: 19726489.

[9]. Silvola AS, Rusanen J, Tolvanen M, Pirttiniemi P, Lahti S. Occlusal characteristics and quality of life before and after treatment of severe malocclusion. Eur J Orthod. 2012 Dec;34(6):704-9. PubMed PMID: 21750239.

[10]. Tajima M, Kohzuki M, Azuma S, Saeki S, Meguro M, Sugawara J. Difference in quality of life according to the severity of malocclusion in Japanese orthodontic patients. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2007 May;212(1):71-80. Pub- Med PMID: 17464106.

[11]. Olkun HK, Sayar G. Impact of Orthodontic Treatment Complexity on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Turkish Patients: A Prospective Clinical Study. Turk J Orthod. 2019 Sep;32(3):125-131. PubMed PMID: 31565686.

[12]. Marques LS, Barbosa CC, Ramos-Jorge ML, Pordeus IA, Paiva SM. [Malocclusion prevalence and orthodontic treatment need in 10-14-year-old schoolchildren in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais State, Brazil: a psychosocial focus]. Cad SaudePublica. 2005 Jul-Aug;21(4):1099-106. PubMed PMID: 16021247.

[13]. Onyeaso CO. An assessment of relationship between self-esteem, orthodontic concern, and Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI) scores among secondary school students in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int Dent J. 2003 Apr;53(2):79-84. PubMed PMID: 12731694.

[14]. Agou S, Locker D, Muirhead V, Tompson B, Streiner DL. Does psychological well-being influence oral-health-related quality of life reports in children receiving orthodontic treatment? Am J OrthodDentofacialOrthop. 2011 Mar;139(3):369-77. PubMed PMID: 21392693.

[15]. Birkeland K, Bøe OE, Wisth PJ. Relationship between occlusion and satisfaction with dental appearance in orthodontically treated and untreated groups. A longitudinal study. Eur J Orthod. 2000 Oct;22(5):509-18. Pub- Med PMID: 11105407.

[16]. de Oliveira CM, Sheiham A. Orthodontic treatment and its impact on oral health-related quality of life in Brazilian adolescents. J Orthod. 2004 Mar;31(1):20-7. PubMed PMID: 15071148.

[17]. Shaw WC, Addy M, Ray C. Dental and social effects of malocclusion and effectivenessof orthodontic treatment: a review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1980 Feb;8(1):36-45. PubMed PMID: 6989548.

[18]. Johal A, Cheung MY, Marcene W. The impact of two different malocclusion traits on quality of life. Br Dent J. 2007 Jan 27;202(2):E2. PubMed PMID: 17260428.

[19]. Albino JE, Cunat JJ, Fox RN, Lewis EA, Slakter MJ, Tedesco LA. Variables discriminating individuals who seek orthodontic treatment. J Dent Res. 1981 Sep;60(9):1661-7. PubMed PMID: 6943159.

[20]. De Baets E, Lambrechts H, Lemiere J, Diya L, Willems G. Impact of selfesteem on the relationship between orthodontic treatment need and oral health-related quality of life in 11- to 16-year-old children. Eur J Orthod. 2012 Dec;34(6):731-7. PubMed PMID: 21750244.

[21]. Jokovic A, Locker D, Stephens M, Kenny D, Tompson B, Guyatt G. Validity and reliability of a questionnaire for measuring child oral-health-related quality of life. J Dent Res. 2002 Jul;81(7):459-63. PubMed PMID: 12161456.

[22]. Harter S. Manual for the self-perception profile for adolescents. University of Denver, Denver. 1988.

[23]. Hagborg WJ. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and Harter’s Self- Perception Profile for Adolescents: a Concurrent Validity Study. Psychol Sch. 1993;30(2):132–6.

[24]. O'Brien K, Wright JL, Conboy F, Macfarlane T, Mandall N. The child perception questionnaire is valid for malocclusions in the United Kingdom. Am J OrthodDentofacialOrthop. 2006 Apr;129(4):536-40. PubMed PMID: 16627180.

[25]. Foster Page LA, Thomson WM, Jokovic A, Locker D. Validation of the Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ 11-14). J Dent Res. 2005 Jul;84(7):649- 52. PubMed PMID: 15972595.

[26]. Marshman Z, Gibson BJ, Benson PE. Is the short-form Child Perceptions Questionnaire meaningful and relevant to children with malocclusion in the UK? J Orthod. 2010 Mar;37(1):29-36. PubMed Erratum in: J Orthod. 2010 Jun;37(2):140. PMID: 20439924.

[27]. Bernabé E, Sheiham A, de Oliveira CM. Impacts on daily performances related to wearing orthodontic appliances. Angle Orthod. 2008 May;78(3):482-6. doi: 10.2319/050207-212.1. PMID: 18416624. [28]. Lerner DJ, Levine S. Health-related quality of life: origins, gaps and directions. Adv Med Sociol.1994;5:43-65.

[29]. Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995 Jan 4;273(1):59-65. PubMed PMID: 7996652.

[30]. Baker SR, Mat A, Robinson PG. What psychosocial factors influence adolescents' oral health? J Dent Res. 2010 Nov;89(11):1230-5. PubMed PMID: 20739689.

[31]. Clijmans M, Lemiere J, Fieuws S, Willems G. Impact of self-esteem and personality traits on the association between orthodontic treatment need and oral health-related quality of life in adults seeking orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod. 2015 Dec;37(6):643-50. PubMed PMID: 25700991.

[32]. Sischo L, Broder HL. Oral health-related quality of life: what, why, how, and future implications. J Dent Res. 2011 Nov;90(11):1264-70. PubMed PMID: 21422477.