Evaluation of Fever Management Practices in Rural India

Jalpa B Manjariya1, Rima Shah2*, Ankita M Miruliya3

1 Medical Officer at primary health centre, Botad, Gujarat, India.

2 Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacology, GMERS Medical College and General Hospital, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India.

3 Junior Resident, GMERS Medical College and General Hospital, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India.

*Corresponding Author

Dr. Rima Shah,

Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacology, GMERS Medical College and General Hospital, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India.

Tel: +919913175808

E-mail: rimashah142@gmail.com

Received: May 15, 2020; Accepted: July 29, 2020; Published: July 31, 2020

Citation: Jalpa B Manjariya, Rima Shah, Ankita M Miruliya. Evaluation of Fever Management Practices in Rural India. Int J Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2020;9(1):323-330. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2167-910X-2000051

Copyright: Rima Shah© 2020. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Precision regarding treatment of fever is reportedly low among the rural regions of India, leading to its irrational

management. This study evaluates fever management practices followed by physicians at primary health centre and

correlate this with standard fever management guidelines.

Methods: One hundred and forty patients admitted to hospital with fever were enrolled in the study. Patient’s demographic

profile and presenting symptoms were precisely studied along with their vital parameters. Patients were divided into two

groups (A&B), with and without treated as per standard guidelines. Duration of illness, treatment with various drugs and

clinical investigation of patients with fever were analysed statistically as outcome analysis.

Results: Majority of patients (47.86 %) belonged to age of 18-30 years. Symptoms related to Upper respiratory tract infection

(URTI), such as cough and rhinorrhoea, were the most common symptoms (104 patients, 74.28%). Most common clinical

diagnosis was viral URTI in both the groups followed by enteric fever, acute gastroenteritis etc. No statistical significance

observed in duration of illness in both groups. All the patients of group A were advised laboratory investigations to confirm

the diagnosis as per the standard management protocol. Most frequently ordered investigations were complete blood count

and peripheral smear for malarial parasite. Average number of drugs prescribed was 2.94 and 4.03 in group A and B (p value

0.001). 8.33% and 18.75% were belonged to category of more than 5 drugs per prescription (polypharmacy) in group A and

B respectively. Amoxicillin and Azithromycin were the most preferentially prescribed antibiotics. 90% and 20% of antibiotics

were prescribed appropriately (P=0.01) as per guidelines in group A and B respectively. Co-prescription of famotidine, pantoprazole

etc was significantly high in group B (p<0.05).

Conclusion: A large number of patients were prescribed with antibiotics without accurate confirmation of bacterial infections

which was contradictory to standard guidelines of fever management practice. Hence increased awareness for rational

fever management is desirable among clinical practitioners in rural India.

2.Introduction

3.Methodology

4.Results

5.Discussion

6.Conclusion

7.References

Keywords

Fever; Management Principles; Symptomatology; Clinical Examination; Laboratory Investigations for Fever; Antibiotics Usage.

Introduction

Fever is considered as one of the most common clinical reasons

for physicians, accounting for about one-third of all presenting

conditions in adult population [1, 2]. Fever, an elevation in core

body temperature above the daily range (98.6ºf) for an individual,

is a characteristic feature of most infections but is also found in a

number of non-infectious diseases such as autoimmune and carcinoma.

Fever is a physiological mechanism with beneficial effects in fighting

infection and it is usually not associated with long-term neurologic

complications. The only purpose for treating fever must be

to relieve the discomfort [3]. Concerns of patients about serious

causes of fever (ie, severe bacterial infections) and misconceptions

about fever as a sufficient trigger of brain damage have led

to the spreading of ‘fever-phobia’. Several studies have reported a

high percentage of adult population consuming antipyretics and

antibiotics even when there is minimal or no fever, with wrong

dosages or with insufficient intervals between the doses [3, 4].

The inappropriate management of fever with irrational use of

antipyretics or antibiotics may delay the diagnosis and increase the

risk of overdose or significantly contributing to antibiotic resistance.

Moreover, other factors may increase drug toxicity such as

the alternate/combined use of two antipyretics or combination

of antibiotics, the use of other formulations with other medicaments,

and the administration of these drugs in the presence of

contraindicated underlying diseases. Finally, overtreatment may

have a significant economic impact in low-middle income and

high income countries. Antipyretics and antibiotics are most preferred

self-method of managing fever and there has been an increase

in this preference over the past two decades from 67% to

more than 90% (91% to 95%) [4].

Fever can pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to the health

workers, particularly in limited resource settings. A number of

viruses, bacteria, protozoa and rickettsia can cause fever [5, 6].

The non-specificity of symptoms and signs and lack of availability

of accurate diagnostics not only test the clinical mettle of even

astute physicians but often leads to irrational use of antibiotics

and antimalarials. Some fever syndromes have a more clear localization

to skin and soft tissue (abscess or cellulitis), meninges or

neural tissue (headache, neck-stiffness, altered sensorium with or

without focal neurological signs), respiratory tract (cough, breathlessness),

or urinary tract (dysuria, haematuria). These syndromes

have better developed guidelines for their management. On the

other hand, acute unidentified fever syndromes (suchas feverrash,

fever-myalgia, fever-arthralgia, fever-hemorrhageand fever

jaundice) haveoverlapping etiologies, which makes their diagnosis

and management even more challenging [7, 8].

In order to rationalise and standardise the symptomatic management

of fever in adult population, national health agencies,

WHO and scientific societies have produced and disseminated

clinical guidelines. It has been demonstrated that patients do not

fully comply with these recommendations of use of prescription

drugs, as they used to employ traditional physical means and

administer antipyretics and antibiotics with inappropriate indications

and posology. Moreover, important discrepancies have been

reported between the practices of healthcare professionals and

the recommendations of guidelines [4]. Considering the abovementioned

parameters in treatment of fever, this study has been

designed with aim of evaluating management practices for fever

in rural India.

Methodology

This was a cross sectional observational study conducted in two

primary health care centres of the western India to know the

management principles of fever being followed at rural level. The

study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee

and written informed consent was obtained from all patients

before enrolling them for the study.

All the patients presented to the primary health care centre of ≥

18 years and of any gender, having chief compliant of fever for

at least one day with any other associated symptoms were enrolled

for the study. Patients with delirium, serious patients requiring referral

to higher centrefacility immediately and those requiring intensive care unit admissions were excluded from the study.

Considering the prevalence of fever of unidentified origin in Indian

populations around 80% [9, 10], sample size is 126 at 7%

precision and 95% confidence interval for this study. Few patients

may drop out or lost to follow up (10%) in the entire duration of

the study, so 140 patients were enrolled for the study. Considering

the dropout total 140 patients were enrolled for the defined time

duration of 6 months (November-April 2019).

All the patients fulfilling inclusion-exclusion criteria were interviewed

by the principle investigator. Demographic details, clinical

examination, history of past and family illnesses, drug therapy

and any complications were recorded in a structured case record

form using case papers of the patients and interview. All the

laboratory investigations carried out for the patients and change

in drug therapy after investigations was also recorded. Disease

related details like temperature measurement method and physical

treatment, patient characteristics (age, gender and main symptoms,

including maximal temperature), medication taken with or

without prescription, antibiotics consumed or not and medication

advice followed or not. Physicians were also asked to give information

about temperature measurement during the consultation

and the final diagnosis (like upper/lower respiratory infection, enteric

fever, malaria, sore throat, isolated fever, gastroenteritis, rash,

influenza or other).

All the patients’ treatment protocol was compared with the standard

treatment guidelines issued by the WHO for fever management

and local standard treatment guidelines of the state.

As per all the guidelines for management of fever following steps

are important:

o Take detail history of fever (temp. reading, type of fever, shivering/

perspiration present or not) and associated symptoms.

o With help of symptoms of the system involved each to clinical

diagnosis like respiratory tract illness, GI infection, Urinary tract

infection, malaria etc (provision/clinical diagnosis).

o Confirm the diagnosis with relevant laboratory tests (like CBC,

S. widal test, blood smear examination, stool or urine examination

etc) – confirmed diagnosis.

o Give treatment both definitive and symptomatic as per the confirmed

diagnosis.

o If started with the empirical treatment, before laboratory investigations,

change to definitive treatment.

All case sheets were reviewed for following of these steps and

divided in to two groups (A & B). Group A included the patients

who were treated as per the guidelines and group B included the

patients who were not treated as per the standard guidelines. For

ease of data analysis, those patients advised any laboratory investigations

for confirmation of diagnosis and treatment were

grouped as A and those who were not advised laboratory investigations

were grouped as B.

Use of antipyretics, antibiotics and other supportive medicines

as well as outcome of fever was compared of the patients given

treatment as per standard guidelines with those not treated as per

guidelines.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee

and written informed consent was obtained from all patients

before enrolling them for the study. Participants did not

receive compensation for their participation in this study. All the

patients were given assurance about protecting data confidentiality

and anonymity. Copies of the consent forms were given to

participants and they had the right to refuse participation or withdraw

from the study at any stage without hampering their medical

treatment.

Data analysis was done using Microsoft excel 2010. All the data

are presented as actual frequencies, percentages, mean and standard

deviation. Chi square test was used for comparison of qualitative

data and students’t test was used for quantitative data. P value

less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

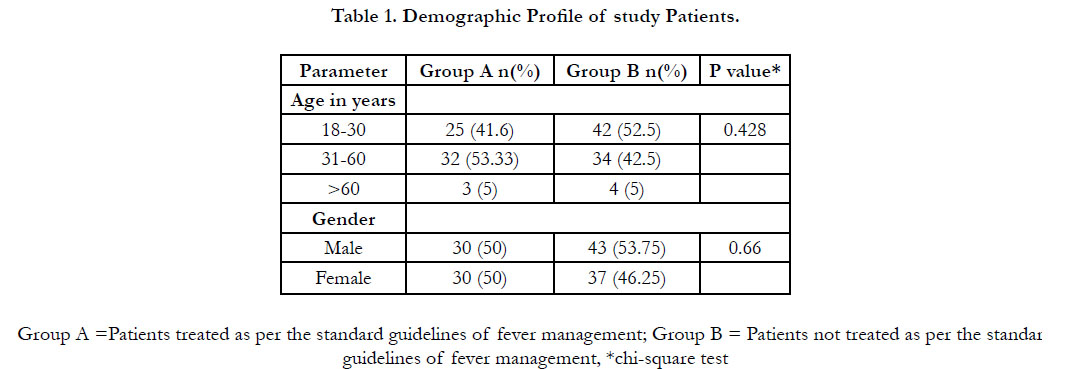

Total 140 patients having fever were enrolled for the study and

their fever management protocol were evaluated. Out of these

140 patients, 60 patients were managed as per standard treatment

guidelines (group A) and 80 patients were not managed as per the

guidelines (group B). Age and gender wise distribution of patients

of both groups is shown in table 1. Majority of patients (47.86 %)

belonged to age of 18-30 years and 30-60 years (47.14 %) while

only 5% patients belonged to > 60 years of age. 52.14 % patient

were male and 47.86 % were females. No statistically significant

difference was found among demographic parameters (p>0.05)

in both groups.

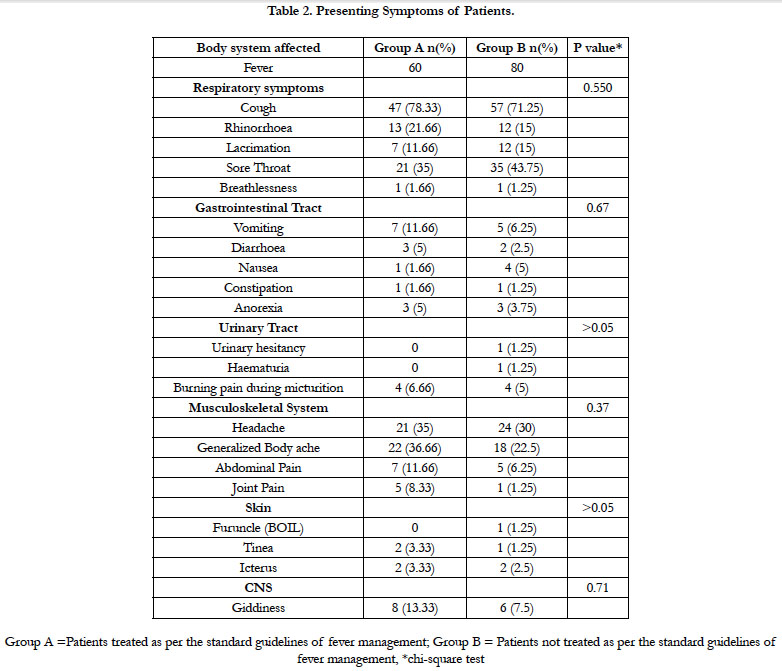

Presenting symptoms of the patients and their body system wise distribution is shown in table 2. Symptoms related to Upper respiratory tract infection (URTS), such as cough and rhinorrhoea, were the most common symptoms (104 patients, 74.28%) as per body system wise distribution. Symptoms related to gastrointestinal system and urinary system were less frequently observed. There was no significant difference between presenting symptoms among both the groups (p>0.05).

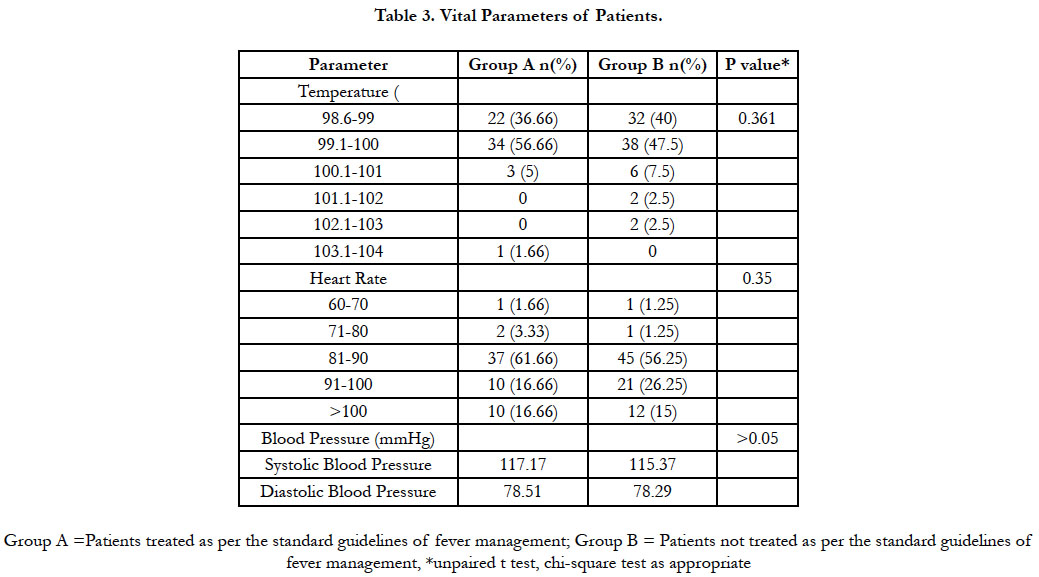

All the patients were subjected to detailed history and clinical examination. Patient’s vital parameters are shown in table 3. Mean temperature of patients was 99.45 and 99.42 in group A and group B respectively. Mean heart rate was 87.39 and 87.45 in group A and B respectively. The mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure in group Apatients was found to be 115.37 mmHg and 78.29 mmHg respectively and in group B it was found to be 115.37 mmHg and 78.29 mmHg respectively, with no statistically significant difference among the groups.

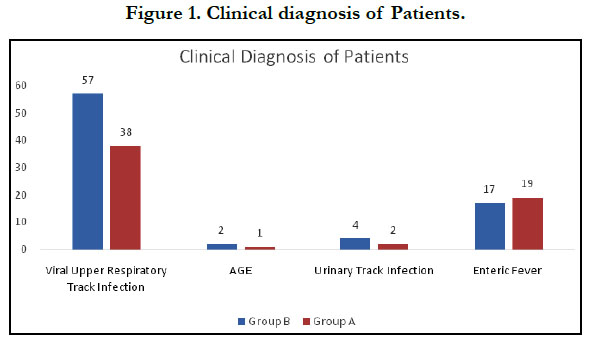

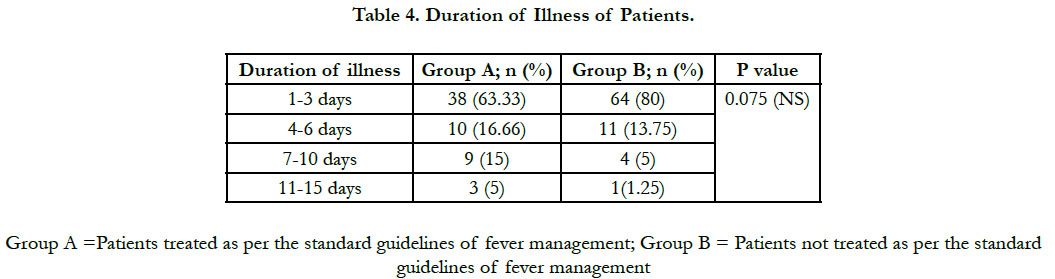

Clinical diagnosis was arrived in all the patients and most common disease was URTI in both the groups followed by enteric fever, acute gastroenteritis and urinary tract infection as shown in figure 1. There was no statistically significant difference was found among provisional diagnosis of the patients (p>0.05). Even there was no statistical significance observed in duration of illness of patients enrolled in both the groups for treatment purpose (table 4).

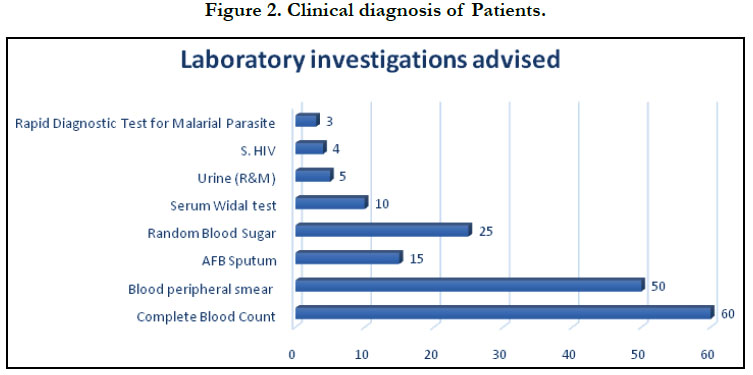

All the patients of group A were advised some or other laboratory investigations to confirm the diagnosis as per the standard management protocol. Most frequently ordered investigations were complete blood count and peripheral smear for malarial parasite. Other laboratory parameters evaluated were liver function test, urine examination, stool examination, blood and sputum culture etc as shown in figure 2. Due to lack of confirmatory tests in group B patients, no definitive diagnosis was reached and thy were treated based on clinical judgement only.

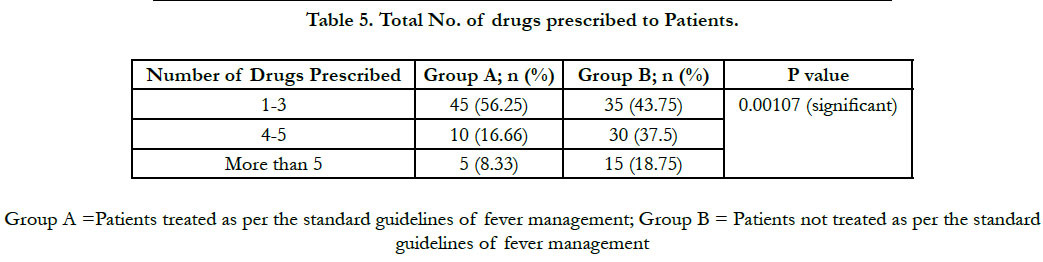

Drug treatment given for the fever patients was compared among both groups. Average number of drugs prescribed was 2.94 and 4.03 in group A and B (p value 0.001). Out of total 140 patients, 56.25% and 43.75% belonged to category of 1-3 drugs prescribed in group Aand Brespectively while 16.66% and 37.5% were belonged to category of 4-5 drugs per prescription and 8.33% and 18.75% were belonged to category of more than 5 drugs per prescription in group A and B respectively (Table 5). There was significantly higher number of drugs prescribed per prescription in group B. (p=0.001).

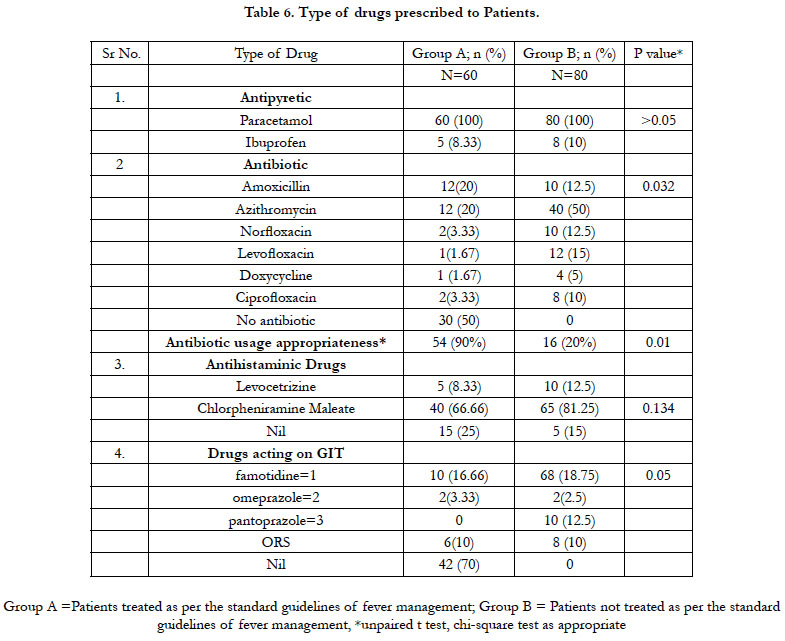

Analysis of drug therapy among both the group patients is shown in table 6. All the patients were prescribed antipyretic, i.e. paracetamol with few patients requiring additional ibuprofen for control of fever. Antibiotics were prescribed to 50% and 100% of patients in group A and B respectively with statistically significant difference (p=0.03). It was found that Amoxicillin and Azithromycin were the most preferentially prescribed antibiotics by the physicians to patients with symptoms of fever.On comparing the use of antimicrobials with the standard treatment guidelines, it was found that 90% and 20% of antibiotics were prescribed appropriately (P=0.01). Prescribing antihistaminic drugs by physicians as an adjuvant therapy to patients suffering from symptoms of fever were reportedly found to be non-significant in both the groups respectively (p>0.05) while drugs acting on GIT like famotidine, pantoprazole etc were prescribed significantly high in group B (p<0.05).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study is the first of its kind investigating the

clinical profile of diverse group of patients suffering from a common

clinical symptom of fever and its management in rural areas

of western India. Our sample was drawn from patients of different

ages came for treatment of fever to primary health care

centres in Gujarat and analysed for its management comparison

with standard treatment guidelines issued by WHO or state government.

Evidences pertaining to Upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs)

are the most commonly encountered diseases for visiting the

doctor, in all groups of patients. URTIs are the major causes of

morbidity and mortality with a worldwide disease burden estimated

at 112 900 000 and 3.5 million deaths, respectively which was

also coinciding with the results of this study that reveals URTIs

as most prevalent cause of fever in majority of patients followed

by Acute gastric enteritis, UTI and enteric fever [11].

Our study found that 28.5% of patients reported using antibiotics

without undergoing laboratory tests to confirm the diagnosis for

bacterial aetiology. Comparatively, a similar study was conducted

by Y. Lui et al., 1999, found a slightly lower prevalence of use

of antibiotics (25.1%) amongst 203 out-patients in Taiwan without

undergoing laboratory examination [1]. Another study conducted in Northern Uganda showed a much higher prevalence

of reported antibiotic use of 62.2% without performing lab tests

contributing a prevalence of 30.4%. This considerable difference

in reported use could likely be as a result of the high prevalence

of non-prescription use of antimicrobials in Northern Uganda

(75.7%) [2]. Again, another study at two hospitals in Ghana found

a higher prevalence of antibiotics in urine (64%) [3].

The significant pervasiveness of prior antibiotic use found in

this study could be attributed to the proliferation of antibiotic

sources, lax drug regulatory legislation and insidious exposure to

antibiotics used in clinical practice and this kind of increased and

inappropriate use of antibiotics has serious implications since it

contributes to selective pressure, favouring the development antibiotic

resistance [4, 12, 13]. Earlier studies reveals that, ceftriaxone

and cefixime seemed to be the first line of antibiotic treatment

for enteric fever however despite of susceptibility, clinical non-response

was seen in around 10 per cent of the patients who needed

combinations of antibiotics with penicillin’s and macrolides as

choice of agents in treatment of fever [14, 15].

Interestingly, more than 25% of patients among the ‘fever symptom

group with no pathological’ were prescribed antibiotics at

primary health care centres. In accordance with treatment guidelines

and recommendations, only patients who have a confirmed

infectious diagnosis are expected to be given an antibiotic prescription [13, 16, 17]. Nonetheless, empirical or presumptive antibiotic

therapy is also accepted when the clinical diagnosis, based

on the presence of a strong clinical suspicion of bacterial infection,

is substantiated by relevant medical history and clinical findings

[13].

According to the WHO and the Indian National Treatment

Guidelines for Antimicrobial Use, presumptive therapy is typically

a one-time treatment given for clinically presumed infection

while waiting for the laboratoryinvestigations [16, 17]. According

to the WHO and the Indian National Treatment Guidelines

for Antimicrobial Use, presumptive therapy is typically a one-time

treatment given for clinically presumed infection while waiting for

the pathological report [18]. It was distinctly observed that the

average duration of treatment was lower in group of patients undergone

pathological examination resulting in lower number of

drugs prescribed which needs to be encouraged. There may be

an increase in compliance, lower cost of therapy and decreased

risk of drug interactions with reduced duration of treatment supported

by earlier studies investigating fever of unknown origin

justified that duration of illness and treatment extends in case of

lack of pathological examination [19, 20].

The practice of prescribing antibiotics to patient groups with no

registered bacterial infection in the absence of laboratory confirmation

could not be considered to be rational. Among the patients

with COPD and RHD, the aetiology of the current episode of

hospitalisation could potentially be expected to be non-bacterial

(e.g, viral infection). However, this could not be confirmed owing

to the absence of laboratory investigations. It is worth mentioning

here that prolonged empirical antibiotic treatment without a

clear evidence of infection is one of the causes of the development

of antibiotic resistance. A higher incidence of prescribing

macrolides, cephalosporinsand fluoroquinolone classes is further

supported by Van Boeckel et al., who observed a significant increase

in the consumption of fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins

globally over the past decade. This increase was mainly attributed

to the increased rates in India and China [21].

In this study both the duration of treatment and the duration

of antibiotic treatment were longer in patients without undergoing

laboratory examination, possibly because of random use of

drug combination without proper justified etiological examination.

This association of longer duration of illness and antibiotic

treatment in patients without laboratory investigations has also

been found in previous studies as well [22, 23].

Irrational use of antibiotics contributes towards difficulties faced

in trying to diagnose specific diseases without the access to diagnostic

tools at health facilities. Various other barriers substantiating

reason for irrational use of antibiotics are the lack of funds

for further diagnostic tests, the shortage of specialists at referral

facilities, deficiencies of the laboratory services (unreliable and

poorly equipped), the limited access to communications and lack

of institutional support and opportunities for training.

A large number of patients were screened over a year period; this

obviates seasonal variations in infectious aetiology, which would

affect antibiotic prescribing strategy with collaboration of pathological

analysis. The same form was used for the data collection

and the process was supervised and monitored by same person at

all hospitals to improve the reliability of the data. The method of collection of data used in the study is robust and reliable. In accordance

with one of the WHO goals of the ‘Global Action Plan’

and in view of limited knowledge of antibiotic use and resistance

patterns, our study suggests that there is a need to conduct similar

long-term surveillance studies globally.

Conclusion

A larger number of patients suffering from fever with their prescribing

occasions were recorded for the study. It was evidently

observed that fever was a factor leading to antibiotic prescription

at health care facility. Large number of patients without any

laboratory investigations and without confirmation of bacterial

infections were prescribed with antibiotics, which could not be

justified. Broad-spectrum antibiotics with irrational combinations

of antibiotics with other adjuvant therapeutics agents were commonly

prescribed in the study for non-indicated conditions may

contribute to elevated duration of treatment. If microbiology reports

could have confirmed the aetiology, some of these might

have been categorised in the non-bacterial group and antibiotic

misuse can be minimised. However, this was not possible to study

in depth owing to the absence of confirmed aetiology and the

nature of the study design (observational). Educational interventions

and continuous learning programs can be implemented for

all practitioners for rational use of drugs specially antimicrobials.

References

- Schmitt BD. Fever phobia: misconceptions of parents about fevers. Am J Dis Child. 1980; 134: 176–181. PMID: 7352443.

- Rkain M, Rkain I, Safi M, Kabiri M, Ahid S, Benjelloun BDS. Knowledge and management of fever among Moroccan parents. East Mediterr Health J. 2014; 20(6): 397–402. PMID: 24960517.

- Thota S, Ladiwala N, Sharma PK, Ganguly E. Fever awareness, management practices and their correlates among parents of under five children in urban India. Int J ContempPediatr. 2018; 5: 1368-1376. PMID: 30035204.

- A Sahib Mehdi El-Radhi. Fever management: Evidence vs current practice. World J Clin Pediatr. 2012 Dec 8; 1(4): 29–33. PMID: 25254165.

- Crump JA. Time for a comprehensive approach to the syndrome of fever in the tropics. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2014; 108(2): 61-2. PMID: 24463580.

- Joshi R, Colford JM, Reingold AL, Kalantri S. Nonmalarial acute undifferentiated fever in a rural hospital in central India: diagnostic uncertainty and overtreatment with antimalarial agents. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2008; 78(3): 393-9. PMID: 18337332.

- Phuong HL, de Vries PJ, Nagelkerke N, Giao PT, Hung le Q, Binh TQ, et al. Acute undifferentiated fever in BinhThuan province, Vietnam: imprecise clinical diagnosis and irrational pharmaco-therapy. Tropical medicine & international health. 2006; 11(6): 869-79. PMID: 16772009.

- Susilawati TN, McBride WJ. Acute undifferentiated fever in Asia: a review of the literature. The Southeast Asian journal of tropical medicine and public health. 2014; 45(3):719-26. PMID: 24974656.

- Singhi S, Chaudhary D, George M Varghese, Ashish Bhalla, N Karthi, S Kalantri, et al., Tropical fevers: Management guidelines. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014; 18(2): 62–69. PMID: 24678147.

- JoshiR, Kalantri SP. Acute Undifferentiated Fever: Management Algorithm. in Update on Tropical Fever. 2015; 1–14.

- Murray C, Lopez A. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997; 349:1436–1442. PMID: 9164317.

- Bertille N, Pons G, Khoshnood B, Fournier-Charrière E, Chalumeau M. Symptomatic Management of Fever in Children: A National Surveyof Healthcare Professionals’ Practices in France. 2015; 10(11):e0143230. PMID: 26599740.

- Liu YC, Huang WK, Huang TS, Kunin CM. Extent of antibiotic use in Taiwan shown by antimicrobial activity in urine. Lancet. 1999; 354(9187): 1360. PMID: 10533872.

- Patil KR, Mali RS, Dhangar BK, Bafna PS, Gagarani MB, Bari SB. Assessment of prescribing trends and quality of handwritten prescriptions from rural India. J PharmaSciTech. 2015; 5: 54– 60.

- Uma B, Prabhakar K, Rajendran S, Lakshmi Sarayu Y. Prevalence of extended spectrum beta lactamases in Salmonella species isolated from patients with acute gastroenteritis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2010: 29: 201– 204. PMID: 20859716.

- Ocan M, Bwanga F, Bbosa GS, Bagenda D, Waako P, Ogwal-Okeng J, et al. Patterns and predictors of self-medication in northern Uganda. PLoS One. 2014; 9(3):1.

- Lerbech AM, Opintan JA, Bekoe SO, Ahiabu MA, Tersbøl BP, Hansen M, et al. Antibiotic exposure in a low-income country: Screening urine samples for presence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in coagulase negative staphylococcal contaminants. PLoS One. 2014; 9(12):1–18. PMID: 25462162.

- Vila J. Update on Antibacterial Resistance in Low-Income Countries: Factors Favoring the Emergence of Resistance. Open Infect Dis J. 2010; 4(2):38–54.

- Murray C, Lopez A. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997; 349:1436–1442. PMID: 9164317.

- Petersdorf RG, Beeson PB. Fever of unexplained origin: report on 100 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1961; 40:1–30. PMID: 13734791.

- Dougherty TJ, Pucci MJ. Antibiotic discovery and development. Antibiotic Discovery and Development. 2014; 1–1127.

- Opintan JA, Newman MJ, Arhin RE, Donkor ES, Gyansa-Lutterodt M, Mills-Pappoe W. Laboratory-based nationwide surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Ghana. Infect Drug Resist. 2015; 8: 379– 89. PMID: 26604806.

- National Centre for Disease Control India. India national treatment guidelines for antimicrobial use in infectious diseases. Version 1.0. New Dehli, 2016: 1–64.

- Bennet JE, Blaser MJ, Dolin R. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- Davey P, Wilcox M, Irwing W. Antimicrobial chemotherapy. 7th edn. Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Van Boeckel TP, Gandra S, Ashok A, Quentin Caudron, Bryan T Grenfell, Simon A Levin, et al. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014; 14: 742–50. PMID: 25022435.

- World Health Organization. The evolving threat of antimicrobial resistance: options for action. WHO Publications. Geneva, 2014.

- WHO. Promoting rational use of medicines: core components. WHO Policy Perspect Med. 2002.