Melanoma on Congenital Nevi: Case Report

Niema Aqil*, Ghita Senhaji, Sara Elloudi, Hanane Baybay, Fatima Zahra Mernissi

Dermatology, University Hospital Hassan II, Fès, Morocco.

*Corresponding Author

Niema Aqil,

Dermatology, University Hospital Hassan II, Fès, Morocco.

E-mail: niemaaqil90@gmail.com

Received: July 24, 2018; Accepted : August 13, 2018; Published: August 17, 2018

Citation: Senhaji G, Elloudi S, Baybay H, Mernissi FZ, Aqil N. Melanoma on Congenital Nevi: Case Report. Int J Clin Dermatol Res. 2018;6(5):180-183. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2332-2977-1800041

Copyright: Aqil N© 2018. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Introduction: Congenital nevi occur in about 1% of newborns. The most used classification is based on their size; small congenital naevus when the largest diameter is less than 1.5cm, intermediate naevi for those between 1.5 and 19.9cm, wide naevus when the diameter is greater than 20cm, and giant naevus when the size is greater than 40cm, with frequent satellite lesions. The risk of transformation into melanoma is estimated at 6.3% for giant nevi, it usually occurs before the age of 20, hence the indication of early excision. This risk is even lower as the size of the nevus is small, and the transformation is usually late. We report the case of a patient with melanoma occurring on a congenital melanocytic naevi of intermediate size.

Case Presentation: We report the case of a 54-year-old patient, with no pathological antecedents, who was born with a congenital nevus of the right shoulder with onset 7 months ago of a nodule within the old lesion, increasing rapidly of which the histological study had concluded to a melanoma.

Discussion: Melanoma can also occur in congenital nevi less than 10cm in size. They can be considered as precursors of melanoma. Because of their large number and frequency, prophylactic excision of all these nevi is not feasible. However, they should be removed as soon as possible when clinical or dermoscopic changes are observed.

2.Introduction

3.Case Presentation

4.Discussion

5.Authors’ Contribution

6.References

Abbreviations

CMN: Congenital Melanocytic Nevus; PN: Proliferative Nodule.

Introduction

Congenital melanocytic naevi (CMN) are found in 1-2% of newborns. They are due to a proliferation of typical melanocytes in the dermis, epidermis or both. They are usually located at the proximal parts of the limbs, trunk, scalp and neck, but may be on any other surface of the skin. Their pigmentation can range from light brown to dark brown and depends on the melanin subtype and its concentration. Histological features may be heterogeneous within the same nevus [1]. Their classification usually depends on their size. Several classifications exist and the most used is the classification proposed by Krengel et al., in which the CMNs are listed in four groups according to the size of the nevus [2-5]. The risk of developing melanoma on a congenital nevus is correlated with the size of the nevus. The risk for small single CMN is very low, whereas where the CMN is > 40 cm projected adult size, and accompanied by multiple smaller CMN, the lifetime risk has been estimated at 10-15% [1, 6, 7]. In this case, we will present a patient with nodular melanoma discovered at the center of a CMN of intermediate size.

Case Presentation

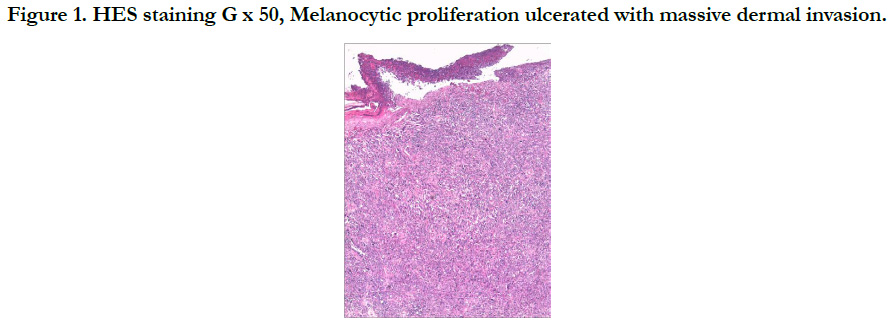

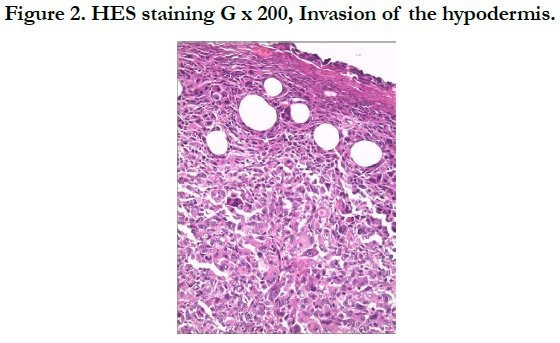

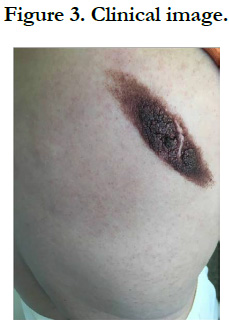

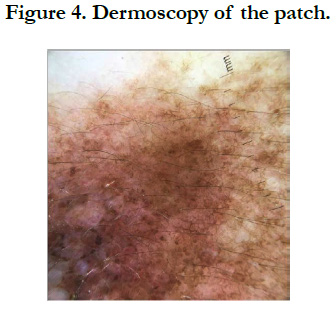

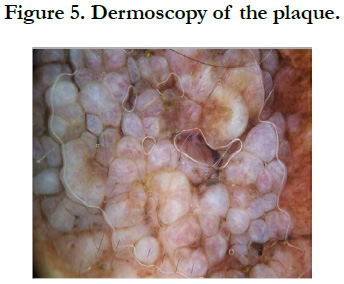

Our patient is a 54-year-old woman who has been hypertensive for one year on treatment. She was born with a medium-sized congenital nevus located at the posterior surface of the right shoulder. For which, she never consulted. Until 7 months ago there was the appearance of a painful, bleeding, rapidly growing nodule on the congenital nevus, which prompted her consultation where a biopsy was performed and final pathological examination verified that it was a nodular melanoma with ulceration, Clark V, Breslow with 3.5mm thickness. The mitotic rate was 7mitosis/field and the presence of vascular embolus (Figure 1, 2). Subsequently, the patient presented herself in our training. The dermatological examination found an homogeneous pigmented, non-infiltrated, oval, well-defined, regularly contoured patch, measuring 9cm/ 3cm, centered by an heterochromous pigmented plaque, with a nippled surface, painless, non-bleeding at contact, making 5 cm of long axis, with presence within the plaque of a slightly hypertrophic linear scar (Figure 3). The dermoscopy had objectified the presence of a peripheral network with points and globules within the patch and a perifollicular hyperpigmentation (Figure 4), and on the plaque, the presence of a papillomatous appearance, with an heterogeneous pigmentation, a polymorphic vascularization made of comma, linear, arborizing and hairpin vessels, the presence of pseudo-comedones and the presence of terminal hair (Figure 5). The rest of somatic examination was normal. During her hospitalization, an extension assessment was made of a cerebro-cervico-thoraco-abdominopelvic scan and an ultrasound of ganglion areas returning without abnormalities. Then she was referred to the department of plastic surgery where she received a resection of the entire nevus with margins of 2cm, and was put under guided healing. Final pathological evaluation confirmed free margins; no other melanoma sites were confirmed.

During the follow-up, ultrasonography of the axillary lymph node area showed the appearance of suspected lymphadenopathy, resulting in lymph node dissection that confirmed the metastatic nature of the lymph nodes. The patient was subsequently referred to oncology and radiotherapy department for further treatment.

Discussion

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are found in 1% to 6% of newborns [1].

They are presumed to result from errors in migration and proliferation of melanocytic progenitor cells during embryogenesis [1]. Although most CMN are present at birth, a subset termed “tardive nevi” may appear after birth [8]. Clinically, CMN are characterized by a smooth to mammillated surface, light- to dark-brown color, and well-demarcated borders. Over time, they may darken or lighten and acquire coarse hairs. Thus some CMN may show variations in color, borders, and surface [9]. CMN are usually classified according to size into small (<1.5cm), medium (1.5-19.9 cm), and large (>20cm) [10]. The estimated prevalence of CMN ranges from 0.5% to 31.7% 8. Small CMN have an estimated incidence of 1 in 100 live births, whereas large CMN is 1 in 20,000 live births [11-13]. Recent data suggest that patients with very large CMN and many satellite nevi are at greatest risk of developing cutaneous and extracutaneous melanoma and neurocutaneous melanocytosis [13, 14]. Knowledge of the dermoscopic structures and patterns found in CMN can assist in the diagnosis and follow-up of these lesions. Dermoscopic evaluation of a CMN begins with the assessment of specific dermoscopic structures, in particular the pigment network and aggregated globules [15]. The presence of one or more of these structures will confirm that the lesion is a melanocytic lesion [16]. In CMN, the pigment network can be fine, thick, or both. It can be homogeneously distributed throughout the lesion, focal (patchy), or present only at the periphery [16]. Globules can be distributed diffusely throughout the lesion, distributed sparsely or densely, or clustered centrally and surrounded by reticulation. The globules can form a cobblestone-like arrangement or target-like structures in which a halo or a network appears to surround the globules [16]. Other dermoscopic structures frequently observed in CMN include milia-like cysts, perifollicular pigment changes, and hypertrichosis. In addition, almost 70% of CMN will reveal vascular structures under dermoscopy, in particular comma vessels, dotted vessels, serpentine vessels, and target network with vessels [17, 18]. If the dermoscopic of the lesion reveals any of the melanoma-specific structures that are atypical pigment network, streaks, negative pigment network, crystalline structures, atypical dots and globules, off-center blotch, blue-white structures over raised areas, regression structures, peripheral brown structureless areas or atypical vascular structures as it was seen in our case, then a biopsy should be contemplated [15]. It is important to acknowledge that most small and medium CMN are fairly homogeneous clinically and dermoscopically, and melanomas developing in such lesions tend to develop at the dermoepidermal junction. Thus dermoscopy can be relied upon to help in the detection of these melanomas [15]. In contrast, large CMN are often heterogeneous, displaying multiple islands of color and irregular topography, although each “island” within the large CMN tends to be fairly organized and homogeneous in its dermoscopic appearance [17]. That being said, melanom as developing in large CMN often develop below the dermoepidermal junction, and thus dermoscopy cannot be relied upon to help identify these melanomas [15].

The most difficult differential diagnosis of a melanoma arising in a CMN would be a proliferative nodule (PN) developing from the CMN, which is a more frequent occurrence than melanoma [19]. Several studies suggest that the incidence of PNs arising from CMNs ranges from 2.9% to 19% [20-22]. PNs have a stronger tendency to develop from giant CMNs than do melanomas, but they rarely develop from small and medium CMNs [19]. PNs usually develop from CMNs during childhood, and only a few cases have ever been described in adults [23]. Another feature than can help distinguish between PNs and melanomas is the location of the lesion. PNs occur in the dermis of the CMNs. Melanomas tend to arise in the more superficial part of the CMN, such as the epidermis and dermis, in small and medium-sized CMNs. However, in giant CMNs, it is found in deeper tissues [19]. Therefore, the appearance of a nodule in the superficial part of a giant CMN in a child, first suggests a PN. In contrast, the appearance of a nodule in the superficial part of a small or intermediate size CMN in an adult, as in our case, should first rule out the diagnosis of melanoma.

Congenital melanocytic nevi are considered giant or large when greater than 20cm in diameter in an adult or when they cover 2-5% of total body surface. Their malignant potential is well established; they have a high risk of developing melanoma [24]. Moreover, nearly 60% of melanomas in this group occur within the first decade of life [25]. Therefore, early preventive excision of giant nevi is recommended, though this may be surgically difficult depending on size and location [25-33]. On the other hand, only little attention has been given to malignant melanoma on congenital melanocytic nevi less than 10cm in diameter [34]. Rhodes and his collaborators have for the first time systematically investigated the development of melanomas on small CMNs in a large population [35, 36]. In two groups of 234 and 134 patients, respectively, tumor associated CMN less than 4.5cm in diameter were ascertained in 8.1% by histology study and in 14.9% by history. These authors estimated a cumulative melanoma risk of 2.6% to 4.9% for persons with small CMN who live to age 60 years. In view of the fact that small CMN less than 10cm are much more frequent than giant nevi as it was said before [11-13], the malignant potential of the small CMN might be of greater practical importance than that of the large ones [37]. As none of the CMN-associated melanomas in the Rhodes and associates studies occurred before puberty and because such an event was only rarely reported in the literature, these authors suggest that preventive excision may be delayed until the beginning of puberty. Considering that even CMNs less than 10cm in diameter are potential precursors of melanoma, their risk apparently does not depend on the size of the nevus. Since the risk of developing melanoma will continue throughout life, however, we believe that excision could be the prophylactic method of choice for CMNs less than 10cm, too; but this can be postponed until the beginning of puberty. If not, the patient should be fully aware of the risk and typical aspects of melanoma associated with CMN and clinical and dermoscopic monitoring will be considered.

Authors’ Contribution

All the authors contributed for the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data for the work; and drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and the final approval of the version to be published; and the agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- Price HN, Schaffer JV. Congenital melanocytic nevi-when to worry and how to treat: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010 May-Jun;28(3):293-302. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.04.004. PubMed PMID: 20541682.

- Krengel S, Scope A, Dusza SW, Vonthein R, Marghoob AA. New recommendations for the categorization of cutaneous features of congenital melanocytic nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Mar;68(3):441-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.05.043. PubMed PMID: 22982004.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, Odom RB. Andrews' diseases of the skin: Clinical dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0. 2006.

- Rhodes AR, Wood WC, Sober AJ, Mihm JM. Nonepidermal origin of malignant melanoma associated with a giant congenital nevocellular nevus. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981 Jun;67(6):782-90. PubMed PMID: 7243980.

- Bett BJ. Large or multiple congenital melanocytic nevi: occurrence of cutaneous melanoma in 1008 persons. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 May;52(5):793-7. PubMed PMID: 15858468.

- Krengel S, Hauschild A, Schäfer T. Melanoma risk in congenital melanocytic naevi: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2006 Jul;155(1):1-8. PubMed PMID: 16792745.

- Kinsler VA, Chong WK, Aylett SE, Atherton DJ. Complications of congenital melanocytic naevi in children: analysis of 16 years’ experience and clinical practice. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Sep;159(4):907-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08775.x. PubMed PMID: 18671780.

- Rhodes AR, Albert LS, Weinstock MA. Congenital nevomelanocytic nevi: proportionate area expansion during infancy and early childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996 Jan;34(1):51-62. PubMed PMID: 8543695.

- Tannous ZS, Mihm Jr MC, Sober AJ, Duncan LM. Congenital melanocytic nevi: clinical and histopathologic features, risk of melanoma, and clinical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Feb;52(2):197-203. PubMed PMID: 15692463.

- Consensus conference: Precursors to malignant melanoma. JAMA. 1984 Apr 13;251(14):1864-6. PubMed PMID: 6700089.

- Viana AC, Gontijo B, Bittencourt FV. Giant congenital melanocytic nevus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013 Nov-Dec;88(6):863-78. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132233. PubMed PMID: 24474093.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, London: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. p. 1871-1876.

- Kovalyshyn I, Braun R, Marghoob A. Congenital melanocytic naevi. Australas J Dermatol. 2009 Nov;50(4):231-40; quiz 241-2. doi: 10.1111/j.1440- 0960.2009.00553_1.x. PubMed PMID: 19916964.

- Slutsky JB, Barr JM, Femia AN, Marghoob AA. Large congenital melanocytic nevi: associated risks and management considerations. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010 Jun;29(2):79-84. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2010.04.007. PubMed PMID: 20579596.

- Haliasos EC, Kerner M, Jaimes N, Zalaudek I, Malvehy J, Hofmann‐ Wellenhof R, et al. Dermoscopy for the pediatric dermatologist part III: dermoscopy of melanocytic lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013 May-Jun;30(3):281-93. doi: 10.1111/pde.12041. PubMed PMID: 23252411.

- Argenziano G, Soyer HP, Chimenti S, Talamini R, Corona R, Sera F, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: results of a consensus meeting via the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003 May;48(5):679-93. PubMed PMID: 12734496.

- Marghoob AA, Braun RP, Kopf AW. An Atlas of dermoscopy. Abingdon, UK: Taylor and Francis; 2005.

- Changchien L, Dusza SW, Agero AL, Korzenko AJ, Braun RP, Sachs D, et al. Age-and site-specific variation in the dermoscopic patterns of congenital melanocytic nevi: an aid to accurate classification and assessment of melanocytic nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2007 Aug;143(8):1007-14. PubMed PMID: 17709659.

- Yélamos O, Arva NC, Obregon R, Yazdan P, Wagner A, Guitart J, et al. A comparative study of proliferative nodules and lethal melanomas in congenital nevi from children. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015 Mar;39(3):405-15. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000351. PubMed PMID: 25517953.

- Yun SJ, Kwon OS, Han JH, Kweon SS, Lee MW, Lee DY, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk of melanoma development from giant congenital melanocytic naevi in Korea: a nationwide retrospective study. Br J Dermatol. 2012 Jan;166(1):115-23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10636.x. PubMed PMID: 21923752.

- Chen AC, McRae MY, Wargon O. Clinical characteristics and risks of large congenital melanocytic naevi: a review of 31 patients at the Sydney Children's Hospital. Australas J Dermatol. 2012 Aug;53(3):219-23. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2012.00897.x. PubMed PMID: 22671135.

- Ruiz-Maldonado R, Tamayo L, Laterza AM, Durán C. Giant pigmented nevi: clinical, histopathologic, and therapeutic considerations. J Pediatr. 1992 Jun;120(6):906-11. PubMed PMID: 1593350.

- McGowan JW, Smith MK, Ryan M, Hood AF. Proliferative nodules with balloon‐cell change in a large congenital melanocytic nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 2006 Mar;33(3):253-5. PubMed PMID: 16466515.

- Swerdlow AJ, English JS, Qiao Z. The risk of melanoma in patients with congenital nevi: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995 Apr;32(4):595- 9. PubMed PMID: 7896948.

- Kaplan EN, Kaplan EN. The risk of malignancy in large congenital nevi. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974 Apr;53(4):421-8. PubMed PMID: 4815697.

- Reed WB, Becker SW, Nickel WR. Giant pigmented nevi, melanoma, and leptomeningeal melanocytosis: a clinical and histopathological study. Arch Dermatol. 1965 Feb;91:100-19. PubMed PMID: 14237589.

- Lanier JV, Pickrell KL, Georgiade NG. Congenital giant nevi: clinical and pathological considerations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976 Jul;58(1):48-54. PubMed PMID: 935278.

- Pack GT, Davis J. The pigmented mole. Postgrad Med. 1960 Mar;27:370-82. PubMed PMID: 14429678.

- Shaw MH. Malignant melanoma arising from a giant hairy n˦ vus. British journal of plastic surgery. 1962 Jan 1;15:426-31. PubMed PMID: 13976963.

- Pers A. Indikationer for operative behandling. Ugeskr Laeger. 1963;125:613-9.

- Smith Jr JL. Problems related to pigmented nevi and melanoma in children. Cancer Bull. 1972;24:22-6.

- Konz B. Congenital giant Nevi (`giant nevi'). Klin Ther Fortschr Med. 1982;100:669-716.

- Jahr O, Friederich HC. For the operative treatment of large naevi. In negotiations of the German Dermatological Society. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg; 1983. p. 354-354.

- Kirschenbaum MB. The small congenital nevocytic nevus and malignant melanoma. JAMA. 1979 Jul 6;242(1):26. PubMed PMID: 448857.

- Rhodes AR, Melski JW. Small congenital nevocellular nevi and the risk of cutaneous melanoma. J Pediatr. 1982 Feb;100(2):219-24. PubMed PMID: 7057329.

- Rhodes AR, Sober AJ, Day CL, Melski JW, Harrist TJ, Mihm Jr MC, et al. The malignant potential of small congenital nevocellular nevi: an estimate of association based on a histologic study of 234 primary cutaneous melanomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982 Feb;6(2):230-41. PubMed PMID: 7061746.

- Castilla EE, Dutra MD, Orioli-Parreiras IM. Epidemiology of congenital pigmented naevi: I. Incidence rates and relative frequencies. Br J Dermatol. 1981 Mar;104(3):307-15. PubMed PMID: 7213564.

- Kuhn H, Mennella C, Magid M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Kroumpouzos G. Psychocutaneous disease: Clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 May;76(5):779-791. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.013. PubMed PMID: 28411771.