Contradictions and Struggles in the Dialogues of Affection: Development and Validation of the Marital Dialectics Harmony Scale

Iboro F.A. Ottu1*, John O. Ekore2

1 Department of Psychology, University of Uyo, Uyo, Nigeria.

2 Deanship of Educational Services, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and Department of Psychology, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

*Corresponding Author

Iboro F.A. Ottu, PhD,

Department of Psychology, University of Uyo, Uyo, Nigeria.

E-mail: iboro.fa.ottu@uniuyo.edu.ng

Received: December 31, 2018; Accepted: February 05, 2019; Published: February 07, 2019

Citation: Iboro F.A. Ottu, John O. Ekore. Contradictions and Struggles in the Dialogues of Affection: Development and Validation of the Marital Dialectics Harmony Scale. Int J Behav Res Psychol. 2019;7(1):237-246. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.19070/2332-3000-1900042

Copyright: Iboro F.A. Ottu© 2019. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Uncertainties are an integral part of intimate relationships. They exist because people, at certain points, find it difficult to resolve the tension between their desires to simultaneously pursue self and relational goals. Relational contradictions have been found to vary, ranging from uncertainty to dialectics. The present study investigated the validity and reliability of a measure on relational dialectics harmony. The scale measures how relational partners may cognitively project and harmonize their personal-relational tensions to stay connected in healthy relationships. The procedure involved content and principal component analyses and the convergent/discriminant validity evaluation of the new scale with four existing and related measures: the relational maintenance strategies measure, infidelity proneness scale, attributional complexity scale and the marital performance ecology scale which was simultaneously developed. Pilot survey involving 70 married persons yielded a Cronbach alpha of .91. The scale was later administered to 664 couples (1328 respondents) at different stages of their marital relationships. A high internal consistency estimate for the Marital Dialectics Harmony Scale (MDHS) was obtained. An exploratory factor analysis produced a simple factor (eigen value = 3.674) accounting for 52.5% of variability based on seven of the 10 scale items that loaded between .70 and .75 factor pattern coefficient. A single scale was therefore created to represent the Marital Dialectics Harmony Scale with a Cronbach’s alpha of .85. Significant convergent relationships were also found between the Marital Dialectics Harmony scale and each of the four relational measures. The scale has therefore filled an important gap in couples’ empathic research that was hitherto open. It is therefore recommended that researchers adopt the measure for marital assessment and interventions.

2.Abbreviations

3.Introduction

4.Theoretical Foundation of Relational Dialectics in Social Interaction and Personality Development

5.Statement of the Problem

6.Qualitative Process of Instrument Development

6.1 Exploring Dialectical Harmony

7.Sample and Respondents’ Characteristics

8.Instruments

9.Data Analysis

10.Results

11.Discussion

12.Conclusion/Recommendation

11.References

Keywords

Contradictions and Struggles; Dialectical Harmony; Dialogues of Affection; Marriage; Measurement Scale; Relational Tension.

Abbreviations

MDHS: Marital Dialectics Harmony Scale; PES: Performance Ecology Scale; EA: Empathic Accuracy; IPS: Infidelity Proneness Scale; RMSM: Relational Maintenance Strategies Measure.

Introduction

Dialectics as a central word denotes differences. In the domain of relationships where the concept gains much relevance, relational dialectics is concerned with how people in relationships enact their differences, sometimes to the discomfort of their partners. There are constant pushes and pulls on individuals when trying to communicate and build a relationship with another [29]. Relational dialectics is known in communication studies as a theory about close personal ties and relationships that highlights tensions, struggles and interplay between contrary tendencies [21]. For example, Bakhtin (1981) [4] interfaced the relational dialectics theory with five interrelated conceptions that aligns with dialogue as follows: (a) dialogue as constitutive process (b) dialogue as dialectical flux, (c) dialogue as aesthetic moment (d) dialogue as utterance and (e) dialogue as critical sensibility. According to Bakhtin (1981) [4] every utterance enters a struggle between “two embattled tendencies in the life of language” (p. 272), which he referred to as centripetal or centrifugal forces. Centripetal discourses are systems of meaning that move towards the centre and are thus legitimated, while centrifugal discourse are de-centered and marginalized [8]. These dimensions were initially examined by Baxter (2004) [7] in her work: “Relationships as dialogues”. From another perspective, Suter and Norwood (2017) [35] had framed relational dialectics in terms of “critical family communication considerations of power”: “connection of private familial sphere to larger public discourse and structures” and “inherent openness to critique, resistance and transformation of the status quo” as examined earlier in a preliminary study by Suter (2016) [36]. Dialectical tensions are described in the research literature as either contradictions driven by needs or discursive struggles synthesized by competing systems [6].

As modestly observed, each level of reasoning is embedded in a system of thought channeled through communication, and described as follows:|

Communication as a Response to Contradiction: One approach of dialectical tension considers relational dialectics as a system of needs or goals that are independent of communication. This means that communication is merely perceived as an approach or channel to address and resolve or manage these differences. For example Petronio’s (2002) communication privacy management theory amplifies this approach if attention is directed as the tension between disclosure and privacy [6].

Contradictions as Discursive Struggle: Here, dialectical tensions are seen as competing systems of meaning or discourse that are constituted in and through communication [6]. This implies that individuals may present their feelings and thoughts as forms of dialectics which need resolution through constant probing, negotiation and mediation that manifest as latent struggles.

As popularly accepted, previous research was of the view that dialectical tensions could be associated with two incompatible elements. However, recent dialectical research considers more complex dialectical system in which more than two elements are at play [9]. Adler and Proctor (2017) [1] have shown the importance of dialectical elements in the preservation of relationships. They project marital partners as communicators who seek incompatible goals which in turn lead to the emergence of dialectical tensions: conflicts that arise when two opposing or incompatible forces exist simultaneously. They explain the operation of several dialectics including autonomy-connectedness, openness-closeness and novelty- predictability. In an interesting illustration, they depict people in a relationship as those who need autonomy and connectedness at different times, comparing them to people who present selfies and relfies in the social media. In their conception, “relfies are not selfies”. Whereas selfies may suggest a certain level of narcissism, self-absorption or cry for attention within a relationship, a relfie simply says that you value the relationship you share with others and in particular our partner.

From the evolving literature, there is enormous evidence that relationship tension exists in various forms. It may generate from a relational concept known as relational uncertainty (Knobloch & Solomon, 1999, 2002) [25, 26] which is the degree of confidence individuals have in their perceptions of involvement within a relationship. Relational uncertainty, which may stem from a person’s self, partner or relationship sources (Berger & Bradac, 1982) [11] emerged from the relational turbulence model [26, 27]. This model defines relational turbulence as peoples’ tendency to be cognitively, emotionally and behaviourally reactive to dyadic situations. The point of convergence between relational uncertainty and relational dialectics may be the push and pull alternating between the self and the partner. This push and pull are forces in opposite directions which cause tension that needs to be resolved favourably in either direction. When this tension cannot be resolved in a median position, the relationship is at risk. Relational uncertainty is just one explanation of the relational turbulence model. The complementary attribution is the interference from partners’ explanation which suggests that turbulence arises when individuals disrupt each other’s ability to accomplish everyday goals.

Generally, relational dialectics is a fundamental assumption of social and communication theorists that all relationships, romantic or platonic, contain tensions and contradictions. The basic elements in these relationships include totality, which suggests that people in a relationship are interdependent and their well being or otherwise impacts the other member(s) as well; contradiction, which refers to oppositions and uncertainties; motion, which depicts the processual nature of relationships and their change over time; as well as praxis which captures the choices which relationship partners make.

Having surveyed the complex nature of these contradictions, it becomes clear that the survival of marriages depend partly on the cognitive disposition of individuals (Ickes, 1993) [23] at different moments, especially at critical aesthetic moments. Very often, researchers assume that marriage creates stability within relationships (Kurdek, 1991) [28], but such stability depends greatly on the psychological disposition of the parties making up the union. For example, Sommer (2005) [33] suggests that most infidelities in relationships are pursued in order to gain emotional connectedness that may be lacking in existing but emotionally deficient relationships rather than the easily available explanations of the pursuit of sex needs.

Considering these, the primary objective of this study therefore was to develop and validate a scale on relational dialectics harmony using a sample of Ibibio respondents from Nigeria. The study also sought to establish the dimensional nature of the scale, whether it will be a unidimensional or multidimensional measure, in addition to assessing the relationship of the scale with comparable marital scales chosen for that purpose.

Theoretical Foundation of Relational Dialectics in Social Interaction and Personality Development

Dialectical theory examines how relationships develop from the interplay of perceived opposite forces or contradictions and how communicators negotiate these ever-changing processes [2]. It proposes by extension that marital relationships result from interplay of perceived opposite forces or contradictions, and from how relational partners negotiate these ever-changing processes (Baxter, 1988, Baxter & Montgomery, 1996; Cissna Cox & Bockner, 1990; Rawlins in Ross & Anderson, 2002) [2, 10, 31]. According to Baxter (2004) [7], “the core concept in dialectical perspective is after all, the contradiction which represents “a unity of opposites”. In an early work (Montgomery & Baxter, 1998) [31] dialectical theory represented the dialectics between unity and differences within relationships. This shows that the central argument in dialectical theory is the existence of opposing tensions in relationships and how people respond to them.

As Wood (1997) [38] has said: “the dialectical theory is an assertion that there are inherent tensions between contradictory impulses or dialectics and that these tensions and how we respond to them are what we can use to understand how relationships work and how people respond to them”. As measures of personality differences vary between individuals due to issues related to temperament and mental health, dialectical differences is also bound to exist between couples and marital stability will greatly depend on each partner’s level of empathic accuracy.

Statement of the Problem

Among contemporary issues affecting marriages is the prevalence of dialectical tensions or discussive struggles. According to the original relational dialectic model, there were many core tensions (opposing values) in any relationship. Such tensions include autonomy and connectedness, favouritism and impartiality, openness and closedness, novelty and predictability, instrumentality and affection and lastly, equality and inequality. These, according to Baxter and Scharp (2015) [6] are seen in one approach as conditions, needs or goals that are situated outside of relationship communication and are (or should be) managed through communication. In the second approach, dialectical tensions are seen as competing systems of meaning constituted in communication, which helps people to make meaning in their interactions. Since these tensions represent a system of oppositions that logically or functionally negate one another it has a lot of implications on partner decision making within a dyadic arrangement as may be found among couples. In order to harmonize these tensions, a measurement scale was adjudged as an important approach to address the fundamental needs of inclusion, control and affection (Anderson & Ross, 2002) [2] identified for relationship functioning, especially among an African population which has hitherto not been included in a study investigating opposing tensions and responses in relationships.

Based on these, the following question was evolved:

To what extent would the Marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale represent a valid and reliable measure of relational dialectics that will help resolve discussive struggles and other relational contradictions towards a harmonious relationship? In an attempt to answer this question, we hypothesize that the marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale will represent a valid and reliable measure of relational dialectics capable of harmonizing any contradictions and struggles that may be experienced by couples in their routine dyadic transacts.

Method: The study used both qualitative and quantitative methods. The qualitative method was a focus group discussion while the quantitative method was a cross-sectional survey. The focus group study was used to assess the meaningfulness and implications of comparably recognizable dialectical tensions (Baxter & Montgomery, 1996; Montgomery, 1993) [10, 13] in the context of the Ibibios, a homogeneous group living in the Southern belt of Nigeria.

Qualitative Process of Instrument Development

The researchers created an interview guide for the focus group study which include the following:

When people marry, they are expected to understand and know each other properly and be open to each other, but some people may be open or closed, connected or autonomous or someone you can reveal something to or not. Some people may be confused whether to do something for themselves alone or something that will benefit them and their partner. What kind of feeling do you have? Do you judge your partner accurately?”

Em…I have always done something as a married person. Anything I want to do, I will remember that there is someone I marry. Sometimes I can take a decision to do something but will not do it because I consider that it is not very good.

In the process of creating harmony, individuals engage themselves in cognitions of fairness and equity as a way of assuring themselves and trying to equalize or harmonize competing feelings.

Yes, sometimes when I want to do something, I get confused whether the thing is good for the two of us or not.

Some dialectical tensions get in the way of our conscience and help us to create harmony between our thoughts and actions. Some partners may be extremely connected to their spouses to the extent that they feel uncomfortable about personal decisions such as the urge to eat when unaccompanied by the partner. Here, there is a conflict between the proper and “autonomous” decisions to respond to hunger and the reminders of “connectedness” which should add value to the relationship if there was an opportunity to share love in the process of “eating together”. However, some spouses say they are sometimes confused about some information due to their embarrassing content.

Sometimes I can go to the market and after some hardwork I get hungry. I will buy something to eat but because of some feelings I keep that thing to eat it with my husband than just eating it in the market. It is not that my husband will get angry but I just feel guilty as if something is missing in me. When we share things, I fell happy.

I will always feel guilty if I do anything that I did not take my husband into it. Sometimes I will be confused if it is necessary to tell him a particular thing or not, especially if it is something in my family of origin that is not good. A good mind will always direct a person.

The dialectical tension between the need to reveal or conceal information has been seen to overlap with that of being either open or closed. Explorative interviews during the focus group sessions revealed the concerns of a husband on the propriety or otherwise of hoarding or revealing information. From a personal point of view, the respondent believes being open to one’s wife is an ideal option in a relationship but expresses the fear that the virtue in the level of openness depends on who you marry.

I like to reveal things to my wife but because some husbands don’t tell their wives their secrets, I am sometimes confused whether this will affect me negatively. Some people say it is good for a man to have some information to himself. I don’t like this, but it can work against you depending on who you marry.

There may be some partners who keep secrets and convince themselves that one is entitled to a certain space of personal information. Such people claim that certain things are too personal, important, trivial or unimportant to lay it bare to their spouses. No one should be surprised that such spouses may see nothing wrong in procuring secure passwords which they use to keep their partners away from their private phone “transactions”. But their mannerisms and non-verbal behaviour in explaining such situations easily give them away as liars and people internally contending with tensions and struggles about their insincere conduct. This kind of action stems from deep-seated selfishness which could be the foundation for all other forms of deceitful and unfaithful behaviours including infidelity, disrespect, betrayal, disobedience heart heartedness and financial defensiveness. Tensions associated with these transgressions continually put such people on the defensive side of life. During the focus group discussion, a wife commented as follows:

You cannot tell your husband everything. There are some things that are not important to tell your husband…ha…ha…it is not because you don’t love him. If you are doing contribution (etibe) it is not good to begin to tell him before it is time to collect it, because he can put his hope on the money when you have already planned to use it for something else.

Being frank and open in a relationship is an important component of marital satisfaction. During the focus group discussion, some participants spoke of how they work to reduce dialectics by showing sincerity in all dealings with their partner. A participant believes it is inevitable to judge a partner... and this implies the day-to-day exchanges which helps spouses to construct and reconstruct their relationship:

Nobody can say he does not judge his partner. I tell my wife what she has done wrong……I consider her in anything I want to do. You should not pretend…let her know you from the beginning.

There are also partners who believe that their spouses cannot fully integrate with them no matter the level of love they profess. They also believe that it is not possible for them to disclose everything to their partners. However a husband submitted that there is a snag for such behaviour which centeres on the need to spring surprises to the concerned spouse.

You cannot know everything about your wife no matter how she loves you. She will not tell you some things. Even myself, there are some things I do which are not necessary to tell a woman but you still love her. The day I bought a motor cycle I did not tell her, I just brought it home to surprise her.

Some opinions expressed during the focus group study laid emphasis on the cooperation expected from two people who make up the marriage and the need to work wholly for the marriage. Nevertheless there were expressions of the inevitability of experiencing certain dimensions of individuality when the need arises because it is natural to do so. There were arguments that it is impossible to ensure absolute equity in our conduct and behaviours.

Marriage is for two people. Everything I do is for the marriage. But sometimes there are things you just find yourself doing alone, it is natural. For example, if you buy udara (a variety of apply) on the road and eat, must you give the same udara to your husband? No, and that does not make you a selfish woman…otherwise you will have to breath air equally so no one will breath more than the other. You see…ha…it is not easy. I can eat when I am at work to give me strength.

Sample and Respondents’ Characteristics

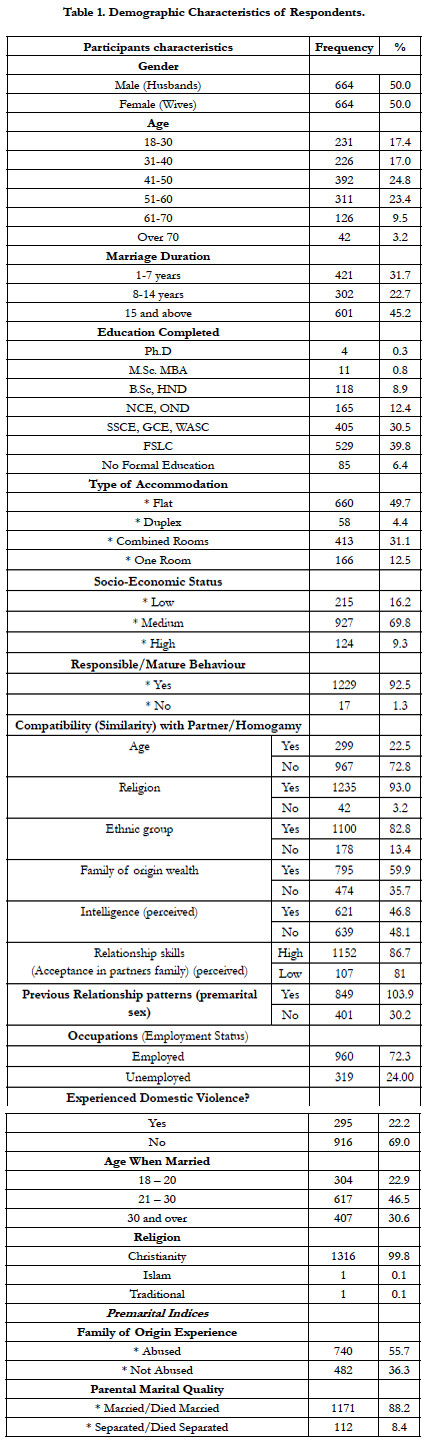

A total of 1672 copies of questionnaire (made up of Section A - Socio-demographic characteristics, the Marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale and four other measures) were administered to participants in nine (9) Local Government Areas of Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. The research setting is predominantly inhabited by the Ibibios who were the purposively targeted participants for the study. The additional scales were used to test the convergent and discriminant validity of the new MDHS. It was reasoned that their (participant’s) long standing marriage-friendly culture (long regulated by the female seclusion phenomenon called mbopo) may help them to easily weather the storms of dialectical contradictions in their marital relationships. A total of 1485 copies of the questionnaire were returned with 1328 copies (664 couples) being considered useable for the study. This represents 79.4 percent response rate. The difference of 157 represented the number of questionnaire copies discarded for inadequate information. The response rate was considered modestly high because the survey method principally involved the use of Investigator-Administered Questionnaire approach in which the questionnaires were filled out in the presence of the researchers or their assistants. The face-to-face administration of questionnaire by the researchers and their assistants principally helped in two ways: (1) The investigators’ presence encouraged participants to respond and (2) The investigator helped to clarify questions for the respondents [30]. We also believe that this has also enhanced the quality of data collected. Moreover, considering the multiplicity of factors capable of eliciting tensions and uncertainty among relational partners, a large number of demographic indices were also investigated. The table below (Table 1) shows the demographic characteristics of the participants who were exclusively couples in intact marriages.

Instruments

The Marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale (MDHS): This scale measures relational dialectics harmony on a 5-point Likert-type, semantic differential scale ranging from 1-5. The midpoint of the scale (3) represents a median point where participants feel equally for the two opposite dialectics. A choice from the midpoint towards the right indicates increasing tendency to locate dialectical harmony in favour of their relationships while choices toward the left indicates decreasing tendency to locate dialectical harmony in favour of their relationship. In other words, choices towards the right favours their relationship while choices towards the left favours partners self preservation.

Face value of the scale was established using a cross-section of academics at the Department of Psychology, University of Ibadan and the scale was pilot-tested to clean up ambiguity and related issues using a small group of Ibibio indigenes. The measure was administered in three versions: English, Nigeria Pidgin and Ibibio languages. For the present sample, Cronbach alpha was 0.85. The items for the scale are presented in Table 2.

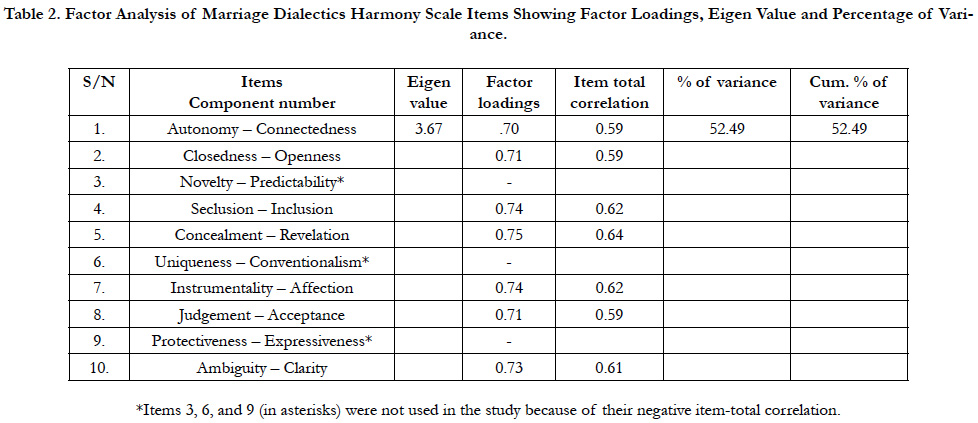

Table 2. Factor Analysis of Marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale Items Showing Factor Loadings, Eigen Value and Percentage of Variance.

• Attributional Complexity Scale: This scale which measures the empathic content and attributional complexity of participants was adapted to reflect interaction by marital partners. Thus, the construct “people” used in the original scale were changed to “my partner”. The scale was developed by Fletcher, Danilovics, Fernandez, Peterson, and Reeder (1986) [19]. It is a 28-item, 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. The Cronbach alpha obtained for this sample was .81 - based on 25 standardized items. Item examples are (1) “I don’t usually bother to analyse my partner’s behaviour” (2) “I think very little about the different ways that my partner and I influence one another”.

• Infidelity Proneness Scale: This scale, developed by Drigotas, Rusbult and Verette (1999) [17], originally had 11 items but was reviewed and 3 new items added while also excluding 2 other odd items making the final instrument into a 12-item scale on a 5-point Likert format. It was provided in the instructions that participants could omit the scale if the contents did not apply to them. However, most of the respondents were aversive to this scale, probably because of the sensitive and explosive nature of infidelity Participants’ aversion to the scale may well be understood because extra-marital involvements are cloaked in greater secrecy. In a classic study on sexual behaviour (Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin & Gebhard, 1953) [24] the question about extramarital sex, for example, was the single, largest cause of participants’ refusal to be interviewed and higher “refusal to answer” rate among those who consented to be interviewed [13]. Based on the data drawn from the study, the Cronbach alpha for this sample was 0.87. Sample items included: (1) How often do you think your husband/wife feels to be emotionally intimate with (an alternative partner)? (2) How physically intimate does your husband or wife feel with this person?

• Performance Ecology Scale: The need to measure the performance domains of marital partners informed the decision to develop the performance ecology scale. It is a 32-item scale on a 5-point Likert format with equal number of direct and reversed items. This scale was simultaneously developed with the Dialectical Harmony Scale and details of its development has also been published separately by the Authors. The scale has a Cronbach Alpha Coefficient of 0.85 in a pilot study. In this study the scale’s reliability coefficient is .79 – based on 23 standardized items. Sample items include: “I believe discussing marital problems with me is my partner’s area of importance and relevance in our marriage” “On the whole, it appears my partner dominates in transmitting genes to our kids than I do.”

• Relationship Maintenance Strategies Measure: This scale, developed by Stafford, Dainton and Haas (2000) [34], measures routine and strategic relationship maintenance behaviours. It is a 31-item Likert-type scale on a 5-point format (reduced from original 7-point format). It has 7 sub-categories: Assurance, openness, positivity, conflict management, shared tasks, advice and social networks. The authors’ alpha coefficients of the subscales range from 0.70 to 0.92. In this study the scale has an overall alpha coefficient of 0.91 for the entire scale. Items samples include: “I say I love you”, “I talk about where we stand”, “I encourage my partner to share his or her feelings with me”.

Data Analysis

Data for this study were analyzed using multiple approaches such as factor (principal component) analysis, divergent and convergent correlations of variables and descriptive statistics for quantitative data. In addition, qualitative data were probed using both inductive and deductive approaches, including transcription, coding and validation. Several procedures such as pattern codingfinding patterns and using them as basis of information organization, descriptive coding – summarizing central themes as well as some efforts at the use of the respondent’s language – which is known as in-vivo coding were employed.

Results

The scale items for measuring dialectical harmony in marriage were subjected to principal component analysis using SPSS 15. Before this, the suitability of data for factor analysis was assessed. The correlation matrix revealed negative coefficients in three items leaving the scale’s alpha coefficient at 0.29 and item mean at 0.7, thus making such items weak in measuring the construct. The items were therefore removed from subsequent analysis. The number of factors to be extracted was determined by an inspection of the scree plot of Eigen values. Using this criterion, the principal component analysis revealed the emergence of a single component with an Eigen value of 3.67 which accounts for 52.49% of the variance. The MDHS items and their factor loadings, Eigen value and percentage of variance are presented in Table 2.

Notably, the scale is a 10-item scale measuring marriage dialectics harmony. Extraction method was the Principal Component Analysis and only one component was extracted. The solution cannot be rotated. In this new scale, the more partners’ self constructions tend towards the right continuum, the more favourably their contradictions were resolved to benefit their relationships. On the other hand, the more they go towards the left, the more these contradictions are resolved in favour of self goals. Instructions for administering the scale are: Please tick (√) or circle any of 1 to 5, what you think applies to you right now in your marital relationship with your spouse after judging yourself with each of these items. If you find yourself towards the right, you are showing high relational or marital skills but if you find yourself towards the left, you are attending to high personal needs in your marital relationship.

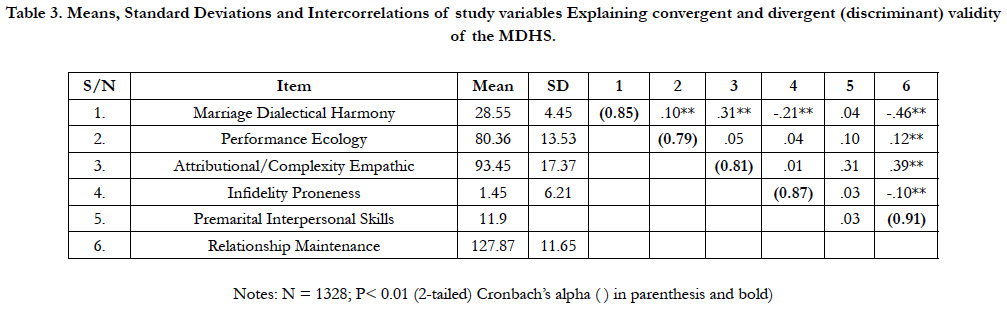

Table 3 shows the intercorrelations, means and standard deviations of the convergent variables to the Marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale. As indicated in the table, marriage dialectics harmony was significantly and positively correlated with Performance Ecology (r= .10, P<.01) and Attribution/Empathic Complexity (r= .31, P<.01). It however correlated negatively with Relationship Maintenance Strategies Measure (RMSM) (r = -.46, P<.01) and also significantly but negatively correlated with alternative partner Infidelity Proneness (r = -.21, P<.01).

Table 3. Means, Standard Deviations and Intercorrelations of study variables Explaining convergent and divergent (discriminant) validity of the MDHS.

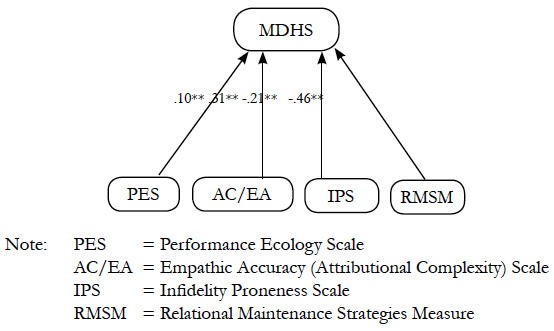

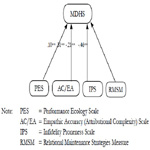

Convergent validity is a sub-type of construct validity. Construct validity conveys the idea that a test designed to measure a particular construct should actually measure that construct. Convergent validity compares two or more measures that are supposed to be measuring the same construct and shows that they are related. Conversely, discrminant validity is intended to show that two or more measures that are not supposed to be related are in fact, unrelated. Both types of validity are a requirement for excellent measurement of construct validity. However, there are many views relating to the best approaches in determining convergent and divergent or discriminant validity. In one view, Carlson and Herdman (2012) [15] recommends that convergent evidence be above .70 between measures in order to consider the instruments as proxies for one another. This is because correlations between theoretically similar measures should be “high” while correlations between theoretically dissimilar measures should be low [37]. But the results of a validity study can be statistically significant even if the validity correlation (coefficient) is quite small. In the same way, the results of a validity study can be non-significant even if the validity correlation (coefficient) is quite large. As a rule, convergent correlation should be statistically significant and discriminant validity should be non-significant [20]. However, Furr and Bacharach’s (2014) [20] findings are not without additional conditions. If a non-significant convergent validity is small then it is certainly evidence against convergent validity. On the other hand, if a significant discriminant validity is large, then it is certainly evidence against discriminant validity. Considering these views, none of our correlations in this study is above .70, hence we conclude that there is no convergence among the measures. The illustration below shows the scales correlational loadings on the Marriage Dialects harmony Scale (MDHS).

Using Cole’s(1987) [16] assumptions that significant correlations indicate that the scales are convergent to each other, we can establish that there is no discriminant validity among the scales. The RMSM is negatively correlated with MDHS. However, as this correlation is relatively small, it may point in the direction of weak divergent validity. Also, there is a weak convergent relationship between PES and MDHS since convergent validity is indicated by significant factor loadings.

These results are not unexpected since all five scales measure one relational index or the other, thus giving some construct validity to the Marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale. As observed, the Infidelity Proneness Scale is inversely correlated (divergent or discriminant) with Marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale and Relationship Maintenance Strategies Measure. This may indicate that the maintenance of an alternative partner in a marriage is unhealthy and therefore detrimental to the primary relationship.

Interestingly, the Marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale is convergently related to all other scales correlated with it. For example, the discriminant validity of performance ecology (r= .10, P < .05*), indicates that performance ecology and all other scales are different from MDHS in its entirety. This suggests that what the performance ecology scale and every other scale measures is quite different from what the MDHS measures. The discriminant validity of MDHS to all other scales is established by the fact that none of the scales loaded up to .50, which is the least level of measurement that can establish any idea of convergence. In reality, an acceptable level of convergent validity is always from .70 and above. These scales were translated into two other languages including Pidgin English and Ibibio languages.

Discussion

This study was conceived to accomplish three interrelated objectives which include (1) to examine various forms of relational tension and develop a suitable scale (MDHS) to see to what extent the marriage dialectics harmony scale could be a valid and reliable measure of marriage dialectics harmony and how it can locate the equilibrium level of commitment among couples. (2) to determine the dimensional components of the scale and (3) determine the relationship of the scale with similar measures of relational commitment. The result of the principal component analysis and the cross-validation with four similar constructs indicated that the scale has favourable psychometric properties. Results of factor analysis show evidence of construct validity for 7 of the ten scale items with overall reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.85. Consequently, we can say that despite the poor loading of 3 items, the 10 items which this study is based represent the Marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale with high reliability and validity indices. Moreover, the scale’s significantly positive correlation with Performance Ecology Scale, Attributional Complexity Scale and Relationship Maintenance Strategies Scale and also significant negative correlation with Infidelity Proneness scale is an indication of wide convergent validity and limited discriminant validity in respect of the variables of the study (Braa & Vidgen, 1999; Coolican’s 2004; Fields’, 2005; &Messick, 1989) [12, 18]. This also suggests that the scale serves as a useful clinical tool in social settings requiring assessment and treatment of marital problems. The result of this study has also revealed that the Marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale is a unidimensional measure of relational harmony.

Moreover, the outcome of this study appears encouraging, especially based on the convergent and discrminant nature of the variables to the Marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale. However, there are still some limitations to the findings of this study. First, the response format of the MDHS and RMSM were such that individual reports reflected participants’ self-perception while the other three scales were “self reports” in respect of one’s perception of his or her spouses’ relational behaviour. This may exert some discrepancy between the social desirability effect of self-reports and the mixed disposition that may manifest in other-related reports. Such lacuna may require further studies to verify or replicate the present findings. In the same way, the social desirability effect could also have been applied in other related reports since spouses were reporting about their marital partners whom they also include as part of their self concept [3].

Conclusion/Recommendation

This study has shown that the newly developed Marriage Dialectics Harmony Scale has filled an important gap in the realm of Psychometric development. It represents another intervention strategy which relational partners should employ in correcting their selfish and indecisive inclinations that may affect optimum interaction among couples. Based on these findings, there is need for researchers to explore social-clinical study of distressed spouses using this scale in a marital setting in order to understand the interventionist use of the instrument in a predictive study. The predictive study may be designed in such a way that the impact of the variables would be tested against each other in a regressional study. Moreover, further research is suggested to verify the discriminant validity of the scale. This may be possible by increasing the number of correlated scales in the study, especially scales expected to show inverse relationship with dialectical harmony. Overall, sustained research will go on to affirm that the more a relationship is characterized by involvement, dependency, commitment and secure attachment (Buun & Dijkstra, 2000) [14], the more it is likely to be free from all rational or irrational threats and tensions that may pull the union down. In addition, couple counselling should routinely be mounted in order to educate spouses on the nature of dialectics occasionally experienced by spouses in the course of navigating difficult marital terrains and landscapes.

References

- Adler RB, Rosenfeld LB, Proctor II RF. Interplay: The Process of Interpersonal Communication. 12th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010.

- Anderson R, Ross V. Questions of communication: A practical introduction to theory. New York: St. Martin's Press; 1998 Jan.

- Aron A, Aron EN, Smollan D. Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992 Oct;63(4):596-12.

- Bakhtin MM. Discourse in the Novel. In M. Holguist (Ed). The dialogic imagination: Four Essaysby M. M. Bakhtin. Austin TX; 1981. p. 259-422.

- Baxter LA, Norwood KM. Relational dialectics theory: Navigating meaning from competing discourses. Engaging theories in interpersonal communication: Multiple perspectives. 2015;2:279-92.

- Baxter LA, Scharp KM. Dialectical Tensions and Relationship. The International Encyclopedia of Communication: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2015.

- Baxter LA. Relationships as dialogues. Personal Relationships. 2004 Mar;11(1):1-22.

- Baxter LA. Voicing relationships: A dialogic perspective. Sage Publications; 2011 Jan 19.

- Baxter LA, Norwood KM, Asbury B, Scharp KM. Narrating adoption: Resisting adoption as “second best” in online stories of domestic adoption told by adoptive parents. Journal of Family Communication. 2014 Jul 3;14(3):253-69.

- Baxter LA, Montgomery BM. Relating: Dialogues and dialectics. Guilford Press; 1996 May 17.

- Berger CR, Bradac JJ. Language and social knowledge: Uncertainty in interpersonal relations. Hodder Education; 1982.

- Braa K, Vidgen R. Interpretation, intervention, and reduction in the organizational laboratory: a framework for in-context information system research. Account Manag Inform Tech. 1999 Jan 1;9(1):25-47.

- Buss DM, Schmitt DP. Sexual strategies theory: an evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychol Rev. 1993 Apr;100(2):204-32. PubMed PMID: 8483982.

- Buunk BP, Dijkstra P. Extradyadic relationships and jealousy. 2000.

- Carlson KD, Herdman AO. Understanding the impact of convergent validity on research results. Organ Res Methods. 2012 Jan;15(1):17-32.

- Cole DA. Utility of confirmatory factor analysis in test validation research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987 Aug;55(4):584-594. doi: 10.1037/0022- 006X.55.4.584. PubMed PMID: 3624616.

- Drigotas SM, Rusbult CE. Should I stay or should I go? A dependence model of breakups. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992 Jan;62(1):62-87.

- Field A. Discovering Statistics using SPSS. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2005.

- Fletcher GJ, Danilovics P, Fernandez G, Peterson D, Reeder GD. Attributional complexity: An individual differences measure. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986 Oct;51(4):875-84.

- Furr RM. Psychometrics: an introduction. Sage Publications; 2017 Dec 12.

- Griffin E. A first look at Communication Theory. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Hazel CE, Vazirabadi GE, Albanes J, Gallagher J. Evidence of convergent and discriminant validity of the Student School Engagement Measure. Psychol Assess. 2014 Sep;26(3):806-814. doi: 10.1037/a0036277. PubMed PMID: 24708075.

- Ickes W. Empathic Accuracy. J Pers. 1993;61:587-610.

- Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE, Gebhard PH. Sexual behavior in the human female. Indiana University Press; 1998 May 22.

- Knobloch LK, Solomon DH. Measuring the sources and content of relational uncertainty. Communication Studies. 1999 Dec 1;50(4):261-78.

- Knobloch LK, Solomon DH. Information seeking beyond initial interaction: Negotiating relational uncertainty within close relationships. Hum Commun Res. 2002 Apr 1;28(2):243-57.

- Knobloch LK. Perceptions of turmoil within courtship: Associations with intimacy, relational uncertainty, and interference from partners. J Soc Pers Relat. 2007 Jun;24(3):363-84.

- Kurdek LA. Predictors of increases in marital distress in newlywed couples: A 3-year prospective longitudinal study. Dev Psychol. 1991 Jul;27(4):627.

- Lusk HM. A study of dialectical theory and its relation to interpersonal relationships. A Study University of Tennessee Honours Thesis Projects. 2008.

- Mitchell ML, Jolley JM. Research design explained. Belmont: Thomson. Wattsworth; 2012.

- Montgomery BM, Baxter LA. Dialectical approaches to studying personal relationships. L. Erlbaum Associates; 1998.

- Solomon DH, Knobloch LK. Relationship uncertainty, partner interference, and intimacy within dating relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2001 Dec;18(6):804-20.

- Sommer, R. The Anatomy of An Affair – Understanding affairs or infidelity and The Real Reasons Why People Cheat. Manitoba: Reena Sommer & Associates; 2005.

- Stafford L, Dainton M, Haas S. Measuring routine and strategic relational maintenance: Scale revision, sex versus gender roles, and the prediction of relational characteristics. Communications Monographs. 2000 Sep 1;67(3):306-23.

- Suter EA, Norwood KM. Critical theorizing in family communication studies: (Re) reading relational dialectics theory 2.0. Commun Theory. 2017 Aug;27(3):290-308.

- Suter EA. Introduction: Critical approaches to family communication research: Representation, critique, and praxis. J Fam Commun. 2016 Jan 2;16(1):1-8.

- Trochim W, Donnelly JP, Arora K. Research methods: The essential knowledge base. Boston, MA: Cengage. 2015.

- Wood JT. Communication Theories in Action. California: Wadsworth Publishing Company; 1997.