Body Dysmorphic Disorder Secondary to Maxillofacial Traumatic Injuries: An Evaluative Analysis

Dr. Vaishali. V*, Dr. Alagappan M, Dr. P. Rajesh

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Chettinad Dental College and Research Institute, Tamil Nadu, India.

*Corresponding Author

Dr.Vaishali. V, MDS,

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Chettinad Dental College and Research Institute, Kelambakkam, Chennai- 603103, Tamil Nadu, India.

Email: vaish712.venkat@gmail.com

Received: November 08, 2022; Accepted: March 10, 2023; Published: March 18, 2023

Citation: Dr. Vaishali. V, Dr. Alagappan M, Dr. P. Rajesh. Body Dysmorphic Disorder Secondary to Maxillofacial Traumatic Injuries: An Evaluative Analysis. Int J Surg Res. 2023;9(1):167-

170.

Copyright: Dr. Vaishali. V© 2023. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

While the management of traumatic maxillofacial injuries is focused in restoring physical form and function to normalcy, the

psychological morbidity that progresses silently during the recovery period remains undealt. BDD is one such disorder that

has never been studied in maxillofacial trauma survivors but highly impacting and thus needs to be taken seriously. This study

aims to evaluate the prevalence of Body Dysmorphic Disorder in patients surgically treated for traumatic maxillofacial injuries

during their postoperative recovery period.

Materials and Methods: A cross sectional analysis of patients surgically managed for the traumatic facial injuries were enrolled

between their sixth week and six months of recovery period. Age, gender, type of injury sustained (disfiguring or non-disfiguring)

were recorded. BDD-YBOCS scale was applied on them and responses were recorded and subjected to statistical analysis.

Results: The population was predominantly male. . 65.6% (n= 42) of them sustained disfiguring injuries. Prevalence of BDD

was observed in 23.4% (n=15). More than 93% of those found with BDD were with mean age of 24.8 and the association was

highly significant with p<0.000.

Discussion: BDD is commonly existent in post-traumatic patients and with simple tools can be diagnosed with ease. Psychological

well-being forms an integral part of a successful management of maxillofacial injuries.

2.Case Report

3.Discussion

4.References

Keywords

Psychological; Dysmorphophobia; Maxillofacial Trauma.

Introduction

Maxillofacial trauma has seen a surge in the 21st century and

considered the silent epidemic of the era. Though remarkable

progress in the surgical restoration of craniofacial fractures has

occurred, little attention has been paid to the emotional and psychological

distress that such trauma may cause [1]. Documentation

of psychological consequences like anxiety, depression, negative

socialization, Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been

done from the late 20th century. Assessment of quality of health

post trauma has been done by the psychologists but the role of

maxillofacial surgeons who share first line relation in the management

of the patient is negligible. Since face is crucial for establishing

a social relation, injury sustained in a trauma that hampers this

harmony impacts the individual’s life significantly. Body dysmorphic

disorder acquired post –trauma is a serious condition that has

to be noticed and addressed at the earliest. In dysmorphophobia

or body dysmorphic disorder, the patient has a subjective feeling

of ugliness or physical defect that he or she believes is noticeable

to others, although appearance is within normal limits [2]. This

study intends to evaluate the prevalence of BDD in post-surgical

patients treated for traumatic maxillofacial injuries and uncover

the latent psychological morbidity that proceeds chronically undermining

the patients’ quality of life.

Materials and Methods

An evaluative analysis of 64 patients who sustained maxillofacial

injuries due to trauma and were treated by the Department of

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery during April 2019 to April 2020

was enrolled in the study. Patients, who were 16 years of age and

above, with surgical treatment (from suturing of lacerated wound

to surgical fixation of complex maxillofacial fractures) at least six

weeks to six months prior to their enrolment, were included in the

study. After obtaining ethical clearance, demographic details were

recorded. The injuries were recorded as disfiguring injuries in case

of significant post-traumatic change of facial orthopaedics or evident scarring and non- disfiguring injuries (no facial asymmetry or

scarring). Those with known psychological or neurologic conditions

were excluded in the study. After obtaining consent from the

subjects, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, Modified for

BDD (BDD-YBOCS) was applied on them and their responses

were recorded. The BDD- YBOCS is a 12-item semi-structured

clinician-rated instrument to measure the severity of BDD in individuals

showing excessive pre-occupation and subjective distress

with physical appearance. They are rated on a 0-4 scale where

0 indicates no symptoms and 4 indicate extreme symptoms. It

measures the severity of BDD-related obsessions, compulsions,

and avoidance and hence was selected to assess the post-traumatic

incidence of BDD in maxillofacial trauma patients. Total score

varies from 0 to 48 and a score higher than 20 denotes the presence

of BDD in the subject. All the data was recorded and subjected

to statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The collected data were analysed with IBM.SPSS statistics software

23.0 Version. To describe about the data, descriptive statistics,

frequency analysis, percentage analysis were used for categorical

variables and the mean & S.D were used for continuous

variables. To find the significant difference between the bivariate

samples in Independent groups the Unpaired sample t-test was

used. For the multivariate analysis the one way ANOVA was used.

To find the significance in categorical data Chi-Square test was

used. Similarly if the expected cell frequency is less than 5 in 2×2

tables, the Fisher's exact test was used. In all the above statistical

tools the probability value .05 is considered as significant level.

Result

Out of the 64 subjects, 71.9% (n= 46) were males and 28.1%

(n=18) were females. 65.6% (n= 42) of them sustained disfiguring

injuries of the face while 34.4% (n= 22) sustained non disfiguring

injuries. Prevalence of BDD was observed in 23.4% (n=15)

of the study population with total score greater than 20 and absent

in 76.6% (n= 49). Highest total score recorded was 31 and

the lowest 0. Mean BDD score of the population was 16.30. No

significant association of BDD with gender was observed in our

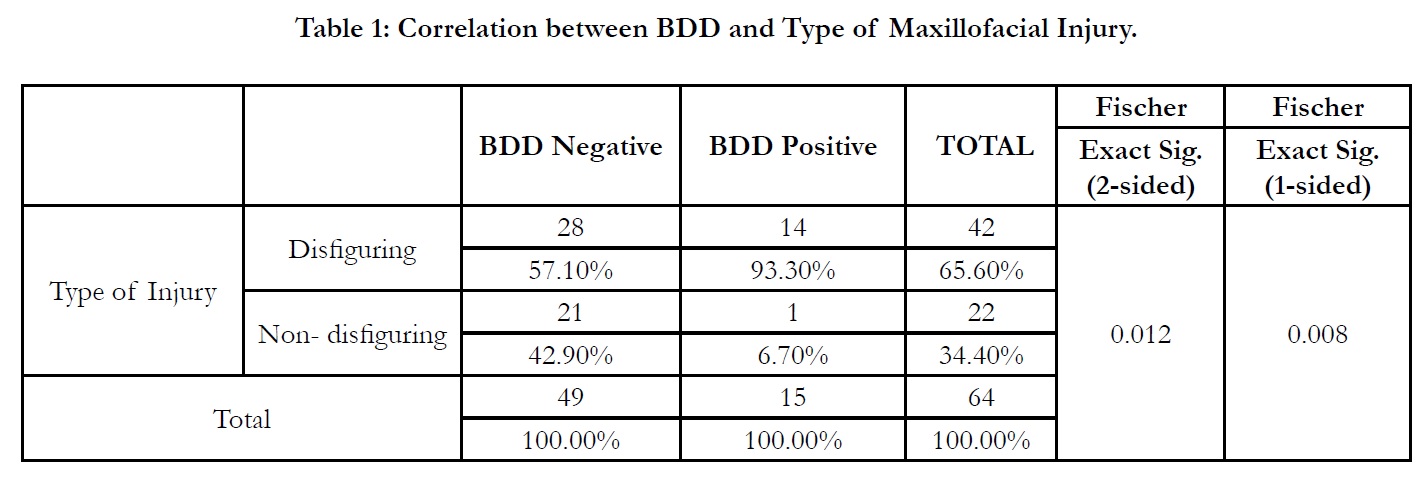

study. Table 1 presents the correlation of BDD with the type of

sustained maxillofacial injuries. 93.3% (n=14) of those with BDD

had sustained disfiguring injuries to the face while 6.7% (n=1) had

no disfiguring injury to the face but was found to have BDD. The

association between the type of maxillofacial injury and incidence

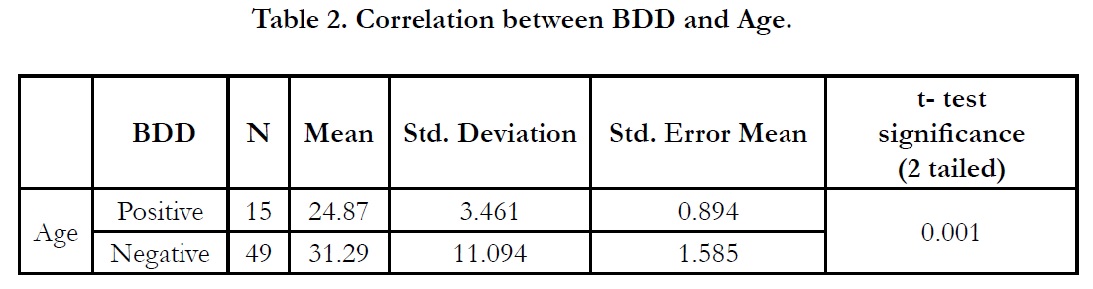

of BDD was statistically significant with p<0.05. Table 2 depicts

the correlation of age and the incidence of BDD. The mean age

of the population positive for BDD was 24.8 ± 3.4 and the association

of BDD bore a high statistical significance with p<0.000.

Discussion

Maxillofacial trauma comprises the major concern of modern day

medicine and public services due to increasing global urbanization.

Due to the complexity and fragility of the anatomical architecture,

the vulnerability of sustaining high impact forces by facial

skeleton is not so uncommon. Road traffic accidents, interpersonal

violence, fall, sport injuries are the most common reasons

of maxillofacial trauma and, significant morbidity and mortality

is associated with the same. The severity of maxillofacial injuries

varies from mild soft tissue injuries like contusion, lacerations or

abrasions to complex fractures of the craniofacial skeleton which

requires respective management protocols. Prompt diagnosis of

the severity of the sustained injury in the emergency department

and early surgical management of the complex injuries reduces

morbidity to a significant extent. Generally, the stability of the facial

construct and reinstating the functional abilities are the prime

objectives of treatment planning, restoration of facial esthetics

is the third pillar of a successful management of maxillofacial

injuries. While the stability and functional aspects of management

greatly influences the restoration of physical form, esthetic restoration

has significant effect on psychological well-being of the

individual in addition to the physical form. Examination of the

mental health of a patient post-trauma is rarely ever recorded and

failure to do so affects the quality of life of the individual thereafter

[3]. Face is vital in recognizing oneself socially and unfamiliar

change in their face as a result of trauma causes grave psychological morbidity [4]. Bisson JI et al reported that 26-41% of those

sustaining maxillofacial injuries suffer from psychological illness

post-treatment ranging from anxiety, depression to Post-traumatic

stress disorder (PTSD)[5]. The importance of identifying and

addressing these consequences are being studied upon by various

researchers recently. In addition to these conditions, there is another

unidentified mental morbidity that is commonly prevalent

in the victims of facial traumatic injuries is the Body Dysmorphic

Disorder (BDD). Maxillofacial injury causes both objective and

subjective changes in facial appearance. Individuals with facial

disfigurement tend to have a negative social imaging and a lower

self-esteem in view of the acquired facial defect [6]. This study intended

to identify such an unexplored yet important psychological

concern uniquely associated with maxillofacial trauma.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder, according to Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of mental disorders-V (DSM-V)[7] criteria is characterized

to be “preoccupation with one or more perceived defects

or flaws in physical appearance that are not observable or appear

slight to others,” and by “repetitive behaviors (e.g., mirror checking,

excessive grooming, skin picking, reassurance seeking) or

mental acts (e.g., comparing his or her appearance with that of

others) in response to the appearance concerns.” In addition, it

causes “clinically significant distress or impairment in important

areas of functioning” and its “symptoms are not better explained

by normal concerns with physical appearance or by concerns with

body fat or weight in individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for eating

disorders.” Generally patients seek medical treatment and they

still remain dissatisfied after treatment. In maxillofacial patient

population, BDD is most commonly observed in patients with

developmental jaw deformities requiring orthognathic surgeries

or perceived defect of the soft tissues requiring aesthetic plastic

surgeries [8]. Prevalence of BDD in post-traumatic acquired deformities

of face when traced had little literature evidence and

has not been studied previously. Most of it goes unrecognized by

the surgeon and also the patient who is unaware of developing

dissatisfaction of the facial defect with time. The more the BDD

is unaddressed, the more impact it has on the social and personal

life of the individual. It also repels the individual from the common

activities due to increasing severity of preconceived notion

regarding their post-traumatic disfigurement chronically affecting

their lives. The diagnosis of BDD can be done with simple tools

like questionnaires during the post-surgical period. Tools that are

commonly employed for diagnosing BDD [9] are Yale-Brown

Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder

(BDD-YBOCS), Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

Axis I Disorders, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP), CGI-I Scale,

Body Dysmorphic Disorder Examination (BDDE), Modified

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Brown Assessment

of Beliefs Scale (BABS), The Cosmetic Procedure Screening Scale

(COPS), The Appearance Anxiety Inventory (AAI), and the BDD

Dimensional Scale.

BDD- YBOCS is semi-structured 12 item clinician rated scale

that assess the severity of BDD in the past week. Since BDD

share similar symptoms with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder,

this scale was re-adapted in diagnosing BDD. The first five items

assess obsessional preoccupations of the perceived appearance

defects (time preoccupied, interference in functioning and distress

due to perceived appearance defects, resistance against preoccupations,

and control over preoccupations). Items 6–10 assess

BDD-related repetitive behaviours (e.g., excessive grooming, mirror

checking) and are similar to items 1–5 (time spent performing

the behaviours, interference in functioning due to the behaviours,

distress experienced if the behaviours are prevented, and resistance

of and control over the behaviours). Item 11 assesses insight

into appearance beliefs (e.g., “I am ugly”), and item 12 assesses

avoidance (e.g., of work/school or social activities) because of

BDD symptoms. Scores for each item range from 0 (no symptoms)

to 4 (extreme symptoms); the total score ranges from 0

to 48, with higher scores reflecting more severe symptoms [10].

Minimum score of 20 is required to confirm the patient to be

positive for BDD [11].

This study results revealed that a considerable proportion of the

patients were found to have developed BDD during their postoperative

recovery period. Out of 64 patients enrolled, BDD was

incident in 23.4% of the patients. BDD in general population has

a prevalence rate of 0.7 to 4%. While in patients seeking cosmetic

surgery and dermatology it is around 6 to 16%. About 10% of

those seeking esthetic jaw correction surgeries were reported to

have BDD. Avinash De Souza [12] reported that prevalence of

psychological comorbidity in patients undergoing reconstructive

surgeries post-tumor resection is comparatively lower than patients

sustained traumatic facial injuries. Trauma induced defects

are often considered to be unnecessary, random and unacceptable

that escalates anger and hatred towards oneself and the situation

that could have been avoided by chance as well as idealizing

one’s pre-injury physical appearance making the adjustment process

more difficult. This supports the results of our study. Also,

the rate of incidence of BDD was higher in patients sustaining

disfiguring injuries of the face comprising about 93.3% of the

total positive BDD patients which was statistically significant.

Also another important finding in our study was, those who were

diagnosed with presence of BDD were young adults with mean

age of 24.8 years and the result was highly significant statistically.

This depicts the dire need to address the psychological impact

of trauma during the recovery period. Failing to do so proves to

be detrimental to the rest of the productive years of these young

adults. 20- 30 years being the formative years of an individual

is loaded with vision and responsibility, self-esteem, confidence

and prime importance to the esthetic outlook of the individual.

When a traumatic event causes facial defect, it impacts social image

of the patient. Patients feel inferior due to the stigma around

the facial appearance and tend to exhibit social withdrawal and

isolation. The prolonged recovery, multiple hospital visits, rehabilitation

methods adds up to the mental exhaustion [12]. When

prompt diagnosis is not made, this can progress chronically stagnating

the progress of the individual and coping with the distress

becomes an uphill task. The psychological needs of a individuals

with post- traumatic facial injuries are unique and are more likely

to report symptoms of depression, anxiety, and hostility when

compared to a matched normal control group for a period of up

to 1 year post trauma [13]. In many cases due to the sub-threshold

prevalence of BDD, a diagnostic dilemma prevails and prevents

from being spot. Thus it is imperative to watch out for the psychological

well-being of the patients during the post-surgical recovery

period. A comprehensive approach has to be made by the

surgeon in managing the patient physically and psychologically.

Lack of understanding of the psychological aspect of the patients

can be attributed to no exposure to psychology as a subject resulting

in low awareness [14]. With simple tools that are enormously

available and easy to apply, could identify the prevalence and severity

of the condition, it should be adapted as a part of the post operative protocol and follow an interdisciplinary management of

the patient for a complete success.

This study has few shortcomings. A larger sample size would have

substantiated the importance of the prevalence of BDD. This

study was done cross-sectionally due to the reduced compliance

of the patients of the region and multiple visits and follow up of

the same could validate the course of the disorder over time. The

sample population was predominantly male and a higher size of

sample would alleviate the doubts entailing the same.

Conclusion

This study exposes that BDD is commonly prevalent in patients

with acquired facial defects due to traumatic injuries and has to

be checked for in every patient during follow up. Adequate psychological

support should be provided to the patients to recover

mentally that will hasten up the process of physical well-being.

Young adults are more prone to develop BDD and are often unaware

of it progressing chronically. Hence a multidisciplinary approach

should be formulated during the treatment of maxillofacial

trauma patients and adequate follow up of the patient should

be done to improve the overall recovery of the patient.

References

- Roccia F, Dell'Acqua A, Angelini G, Berrone S. Maxillofacial trauma and psychiatric sequelae: post-traumatic stress disorder. J Craniofac Surg. 2005 May;16(3):355-60. PubMed PMID: 15915097.

- Thomas CS, Goldberg DP. Appearance, body image and distress in facial dysmorphophobia.ActaPsychiatr Scand. 1995 Sep;92(3):231-6. PubMed PMID: 7484204.

- De Sousa A. Psychological issues in acquired facial trauma. Indian J Plast Surg. 2010 Jul;43(2):200-5. PubMed PMID: 21217982.

- Cunningham SJ. The psychology of facial appearance. Dent Update. 1999 Dec;26(10):438-43. PubMed PMID: 10765787.

- Prashanth NT, Raghuveer HP, Kumar RD, Shobha ES, Rangan V, Hullale B. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Facial Injuries: A Comparative Study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2015 Feb 1;16(2):118-25. PubMed PMID: 25906802.

- Sahni V. Psychological Impact of Facial Trauma.Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2018 Mar;11(1):15-20. PubMed PMID: 29387299.

- de Brito MJ, SabinoNeto M, de Oliveira MF, Cordás TA, Duarte LS, Rosella MF, et al. Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD-YBOCS): Brazilian Portuguese translation, cultural adaptation and validation. Braz J Psychiatry. 2015 Oct-Dec;37(4):310-6. PubMed PMID: 26692429.

- Collins B, Gonzalez D, Gaudilliere DK, Shrestha P, Girod S. Body dysmorphic disorder and psychological distress in orthognathic surgery patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014 Aug;72(8):1553-8. PubMed PMID: 24582136.

- Thanveer F, Khunger N. Screening for Body Dysmorphic Disorder in a Dermatology Outpatient Setting at a Tertiary Care Centre. J CutanAesthet Surg. 2016 Jul-Sep;9(3):188-191. PubMed PMID: 27761090.

- Phillips KA, McElroy SL, Dwight MM, Eisen JL, Rasmussen SA. Delusionality and response to open-label fluvoxamine in body dysmorphic disorder.J Clin Psychiatry. 2001 Feb;62(2):87-91. PubMed PMID: 11247107.

- Brito MJ, Nahas FX, Cordás TA, Gama MG, Sucupira ER, Ramos TD, et al. Prevalence of Body Dysmorphic Disorder Symptoms and Body Weight Concerns in Patients Seeking Abdominoplasty. AesthetSurg J. 2016 Mar;36(3):324-32. PubMed PMID: 26851144.

- Phillips KA. An open-label study of escitalopram in body dysmorphic disorder.IntClinPsychopharmacol. 2006 May;21(3):177-9. PubMed PMID: 16528140.

- Wilson N, Heke S, Holmes S, Dain V, Priebe S, Bridle C, et al. Prevalence and predictive factors of psychological morbidity following facial injury: a prospective study of patients attending a maxillofacial outpatient clinic within a major UK city. Dialogues ClinNeurosci. 2018 Dec;20(4):327-339. PubMed PMID: 30936771.

- Krishnan B, Rajkumar RP. Psychological Consequences of Maxillofacial Trauma in the Indian Population: A Preliminary Study. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2018 Sep;11(3):199-204. PubMed PMID: 30087749.