Clients and Providers’ Perceptions on the Quality and Provision of Contraceptive Services to Youths at Community Level in Rural Uganda: A Qualitative Study

Babirye S1*, Akulume M2, Kisakye AN3, Kiwanuka SN2

1 MakSPH-CDC Fellowship Program/ Department of Health Policy Planning and Management, Makerere University School of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda.

2 Department of Health Policy Planning and Management, Makerere University School of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda.

3 African Field Epidemiology Network (AFENET), Department of Health Policy Planning and Management, Makerere University School of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda.

*Corresponding Author

Susan Babirye,

CDC Fellowship Program, Department of Health Policy Planning and Management,

Makerere University School of Public Health, P.O Box 7072 Kampala, Uganda.

E-mail: babiryes2004@gmail.com

Received: May 02, 2018; Accepted: May 29, 2018; Published: June 12, 2018

Citation: Babirye S, Akulume M, Kisakye AN, Kiwanuka SN. Clients and Providers’ Perceptions on the Quality and Provision of Contraceptive Services to Youths at Community Level in Rural Uganda: A Qualitative Study. Int J Reprod Fertil Sex Health. 2018;5(2):118-125. doi:dx.doi.org/10.19070/2377-1887-1800022

Copyright: Babirye S© 2018. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Contraceptive uptake among youths aged 15-24 years in Uganda remains low at 11%, despite a conducive policy environment and various contraceptive delivery models in the country. We explored the perceptions of youths on the quality of contraceptive services available and the providers’ perceptions towards delivering contraceptive services to young people at community level.

Methods: Qualitative data were drawn from open-ended questions in a survey of 323 sexually active youths aged 15-24 years old. In addition, we conducted four focus group discussions with 48 youths, and eight (8) in-depth interviews with community- level contraceptive providers. We used latent content analysis technique to analyse the data.

Results: A number of gaps in relation to the quality of available contraceptive services were cited by the youths. These included; inconsistencies in the supply of contraceptives, limited contraceptive options, absence of counselling from drug shop operators and perceived technical incompetency among some contraceptive providers. The youths also reported good client relations among Community Based Distributors of contraceptives (CBDs) and drug shop operators. In general, providers did not know that family planning policies existed, although the public healthcare providers and CBDs of contraceptives followed the family planning provision checklists. The providers also had misconceptions about contraceptive use among youths and negative attitudes towards the provision of contraceptives to the young ones and unmarried youths.

Conclusion: To improve on the quality of contraceptive services provided to youths at community level, the inconsistencies in the availability of contraceptives and the negative attitudes by service providers towards dispensing contraceptives especially to the unmarried youths should be addressed. The availability of contraceptive choices too should not be compromised and dispensing contraceptives should be accompanied by adequate information.

2.Abbreviations

3.Inrtoduction

4.Materials and Methods

4.1 Study Site

4.2 Study Design

4.3 Data Collection Methods

4.4 Data Analysis

4.5 Ethical Considerations

5.Results

5.1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Respondents, FGD and IDI Participants

5.2 Youth’s perspectives on quality of services of the different contraceptive providers at community level

4.3 Provider’s perspectives on distribution of contraceptives to youths

6.Discussion

7.Conclusion

8.Acknowledgement

9.References

Keywords

Contraceptive Distribution; Family Planning; Quality of Care; Provider Perspectives; Youths; Qualitative Study; Uganda.

Abbreviations

CBDs: Community Based Distributors; ICPD: International Conference on Population and Development; DSO: Drug Shop Operator; FGDs: Focus Group Discussions; IDI: In-Depth Interviews.

Inrtoduction

A number of statements and conventions have been ratified by different authorities worldwide to uphold the rights of youth to access and use contraception. Despite the supportive policy environment, the rate of unintended pregnancies, particularly among the youth, remains a public health concern. In Sub-Saharan Africa for example, an estimated 14 million unintended pregnancies occur every year and nearly half of these pregnancies occur among women aged 15–24 years [1]. The situation is not any different in Uganda where statistics show that four in every ten pregnancies are unintended, teenage pregnancy rate stands at 25%, and about 15 to 23% of female youths (15-24) have had an abortion [2-4]. The high levels of unintended pregnancy and abortions in Uganda can be attributed primarily to non-use of contraceptives by women who do not want a child soon. Specific to the youth (15-24 years), the stigma associated with premarital sex make many reluctant to openly seek contraceptive services [2] and as a result, several fall prey to teenage and unintended pregnancies as well as sexually transmitted infections [5-7]. Unintended pregnancies especially among the youth have been associated with poor outcomes such as miscarriages, stillbirths, unsafe abortion, and infant or maternal deaths [8, 9].

Research indicates that contraceptive use alone could reduce the consequences of unwanted pregnancies through its benefits that extend beyond the prevention of pregnancy alone to averted maternal morbidity and mortality, including deaths and morbidity from unsafe abortion; and diminished infant morbidity and mortality [1, 10, 11]. Increasing use of contraceptives has been a priority in Uganda since the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo. In fact as a strategy to ensure use of contraceptives, Uganda has several family planning related guidelines and strategic documents that allow access to contraceptive services by every sexually active individual irrespective of age [12, 13]. In addition, contraceptives are free in all public facilities in Uganda [14]. However, this has not translated into elevated use of contraceptives, as contraceptive use among youths aged 15-24 years has remained low (CPR is 11%) [15].

Quality of care has been highlighted to be particularly important for contraceptive uptake [10, 16]. In fact, evidence from various settings has shown a positive association between the quality of contraceptive services and contraceptive use [17-19]. An early study by Rutenberg and Watkins showed that satisfied clients are more likely to revisit the services, pass on positive messages by word of mouth to others, and continue use of a particular contraception method [16]. On the other hand, a study by William and others, found that dissatisfied clients were more likely to share their negative experiences with others and are less likely to return or continue use of family planning services [20]. It is also known that service provider perspectives on provision of contraceptives impact on contraceptive distribution [21]. In order to have effective contraceptive programs for youths, the opinions of youths on the quality of contraceptive services provided through the different delivery approaches have to be taken into consideration. In addition, understanding the limits to care imposed by the providers themselves can further illustrate why certain contraceptive methods are less utilized by youths compared to others and why youths continue to be underserved by the current contraceptive provision network. However, previous research in Uganda has mainly focused on broad contraceptive use among different populations [22-25]. Less research has focused on contraceptive provision from all the existing delivery approaches or even lesser on provision specifically to youths. Therefore, incorporating research on both youths’ perceptions of quality of contraceptive services from the different providers, and providers’ perceptions on provision specifically to the youths is important in gaining understanding of options for enhancing uptake of contraceptives among this sexually active and highly fertile sub-population. Our study explored the perceptions of youths between 15-24 years on the quality of contraceptive services provided by the different providers and the providers’ perceptions towards provision of contraceptive services to youths at community level in Busia district, Uganda.

\

The clients’ perceptions of quality of contraceptive services was assessed basing on a theoretical framework for assessing quality of family planning services proposed by Bruce and Jain [26]. The framework posits that there are six elements that constitute quality of family planning services. These elements reflect attributes of the services that clients consider as critical for contraceptive adoption and continued utilization and include; technical competences of providers, information given to users, choice of contraceptive methods provided, interpersonal relations, continuity mechanisms, and appropriate constellation of services also referred to as appropriateness and acceptability. Not so many qualitative studies have used this framework to assess the quality of services provided to youths in Uganda and elsewhere.

We conducted the study in Buhehe Sub County, Busia District in Eastern Uganda. Busia district has an annual population growth rate of 2.7 per annum. In 2011, the district’s contraceptive prevalence rate was at 37% [27]. We selected Busia as a study district because it had various modes of contraceptive delivery at community level.

In 2011, the population of Buhehe was projected to be 15,739 with 8,184 females and 755 males [27]. More than 40% of the population in Buhehe Sub County was estimated to be less than 18 years old. Buhehe Sub County has two government health centres at level III and II. It also has over 20 drug shops and 20 Village health team members who are trained in the provision of short-term contraceptives at community level. Buhehe Sub County was purposively selected as a study site to ensure representation of all modern contraception providers. Three types of providers existed in this sub county; government (public) health facilities; community based distributors who included VHT members trained to offer contraceptives in the communities and Drug Shop Operator (DSO).

This was a descriptive cross sectional study conducted between May and August, 2012 in Busia district, Uganda. We interviewed 323 youth between the ages of 15 to 24 who had had sexual intercourse within 12 months following the study. We also conducted four Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with sexually active youths including both users and non-users of contraceptives; and eight in-depth interviews (IDI) with Community Based Distributors (CBDs), healthcare providers and Drug Shop Operators (DSO). Throughout the study, we adhered to the RATS guidelines on qualitative research [28].

We included open-ended questions in the survey questionnaire in order to obtain an overview of the youth’s opinions on the use of contraceptives; availability of contraceptive providers, contraceptive options and supplies; quality of counselling, interpersonal relations, provider competence, existence of mechanisms of contraception continuity and assemblage of services. We worked with the local council authorities to generate a list of all the youth in the study area, which was used during sampling of the study participants. Having obtained an overview from the open-ended survey questions, we followed up with FGDs that offered an opportunity to delve into the lived experiences and perceptions of 48 male and female sexually active youths based on the themes that were explored in the open-ended survey questions. We purposively selected FGD participants and conducted a total of four FGDs with current users of modern contraceptives and non-users of modern contraceptives who were sexually active.

In addition we conducted in-depth interviews with eight contraceptive service providers including; four community-based distributors (CBDs), two healthcare providers and two drug shop operators (DSOs). The participants were purposively selected and encouraged to give detailed narratives of their experiences and feelings regarding contraceptive use by youth and distribution of contraceptives. The themes explored in the in-depth interviews included existence of demand for contraceptives among youths; perceived benefits and effects of contraceptive use to youths; accessibility of contraceptive services to youths; availability of supplies; guidelines and norms affecting distribution of contraceptives to youths as well as experiences with provision of contraceptives to the different categories of youths including the unmarried and those below 18 years.

Data were collected by trained research assistants who had completed at least advanced level of education and were conversant with the local language spoken in the study district. The FGDs were moderated by the principle investigator (female) with the help of a male research assistant who is experienced in conducting qualitative research while the IDIs were conducted by the later. The discussions were audio taped after obtaining consent from the participants. Notes were also taken by a research assistant. The FGDs lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. The discussions were held at a convenient venue identified by participants and there was flexibility to explore emerging themes.

Responses from the open-ended survey questions were directly written on to spaces provided on the questionnaire. The FGDs and the IDIs were translated and transcribed into English by a research assistant with experience in translation and transcription of qualitative data. The principle investigator read through all the transcripts several times while making notes on the transcripts to identify the merging themes. Coding of the data and the analysis was done manually. The unit of analysis was the focus group and IDI respectively. We used latent content analysis technique that involves in-depth interpretation of the underlying meanings of the text and condensing data without losing its quality to analyse the data [29]. The codes were grouped into sub categories and themes were identified as highlighted by Graneheim and Lundman [29]. The analysis was discussed among the research team members and discrepancies on coding and other issues that required clarity were settled by discussion. Quotes that best described the various categories and expressed what was aired frequently in several groups were chosen.

We obtained approval from the higher degrees, research and ethics committee of the School of Public Health, Makerere University and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. We obtained written consent from all participants after explaining the purpose of the study. For participants below 18 years and were not married, written consent was sought from their parents or guardians and thereafter they assented to participate. The respondents were informed about the voluntary nature of the study and confidentiality was assured throughout the interviews.

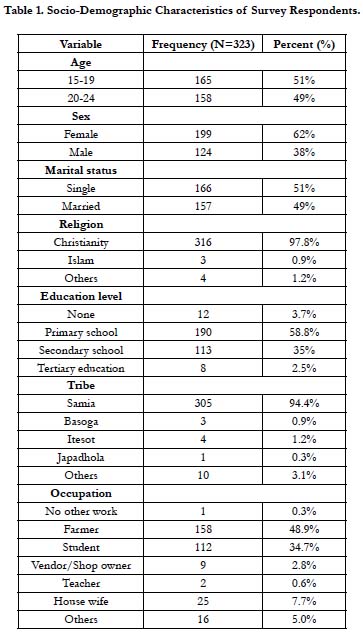

Three hundred twenty three (323) sexually active young people participated in this study. On average, the study participants were 19.5 years (SD=2.8) and the age range was 15-24 years. Most of the respondents 199 (62%) were females. Only 43 (13%) were married (Table 1).

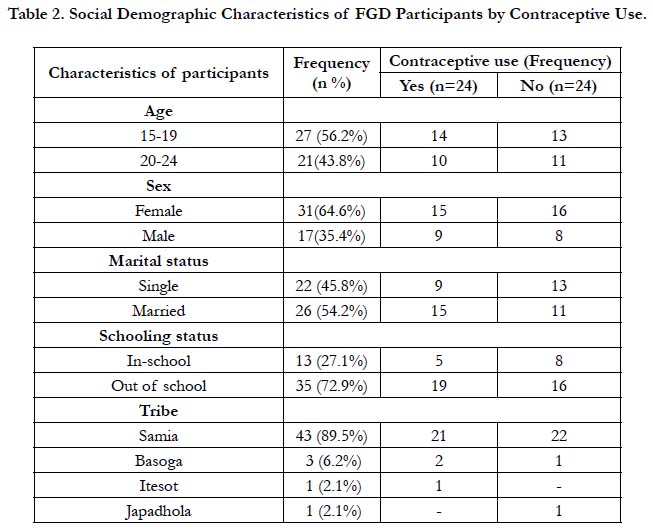

Similarly, 48 young people were engaged in four FGDs. Their age range was 15-24, and 56.2% of the FGD participants were between ages 15-19. Those aged 20-24 years were 43.8%. Fifty four percent of the participants were married. Majority of the FGD participants were female and from the Samia tribe (Table 2).

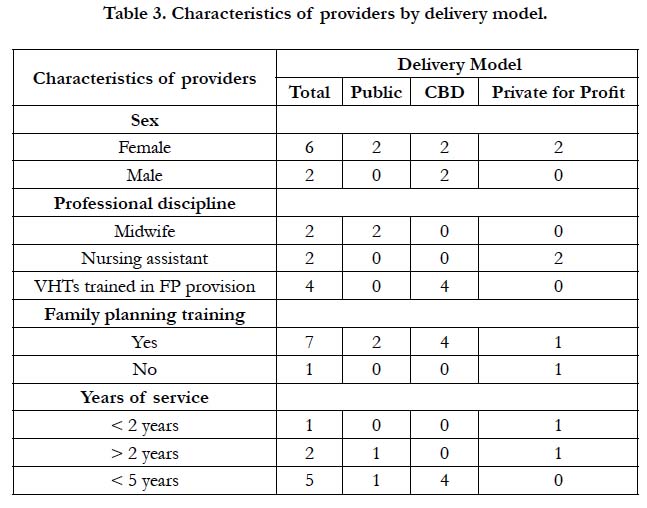

Among the IDI respondents, eight were contraceptive providers; four community-based distributors; two public healthcare providers and two were drug shop operators. The two public healthcare providers were midwives whereas the two drug shop operators were nursing assistants. The four community based distributors included in the study reported having undergone a two weeks training on the provision of injectable and oral contraceptives. The majority (7/8) of the providers reported having more than two years of experience in family planning service delivery (see Table 3).

All participants reported uneven availability of contraceptive choices and supplies from all providers. The youths reported that among all the contraceptive distribution alternatives at community level, the government health centres at least had a variety of methods and often available. Participants revealed that stock outs of contraceptives were common among the drug shop operators and community based distributors. The common methods dispensed by CBDs and drug shops operators were mainly Depo, pills and condoms.

It was noted that even when contraceptives were available, other factors at provider level hindered their access. The youths mentioned limiting factors such as; providers too busy, unwillingness of some providers to dispense contraceptives to youths, the cost imposed by providers on the would-be free contraceptives:

‘If you’re in a hurry, you rather go to a drug shop because at the Bunyadeti [government health centre] the client turn up is big and for CBDs you have to wait for them to finish their domestic chores before you’re served’. Male participant, FGD 3

Throughout all FGDs and open ended survey questions, waiting time at the health facilities was a major concern. On average, respondents mentioned that they spent about two to three hours waiting for services at the government facilities. Some participants reported that left the facility without receiving a service because of the client volumes at the facility.

In regards to the technical competences of providers, all FGDs participants trusted the technical competency of providers at public health facilities. They perceived them to be more qualified, skilled to conduct detailed counselling and managing of the side effects of contraceptives. Drug shop operators on the otherhand were the least trusted among the FGD participants in terms of their technical competences. FGD participants mentioned that drug shop operators were not qualified and inexperienced. There were also complaints that drug shop operators dispensed wrong or expired drugs and did not counsel their clients.

When asked about the quality of counselling received when they went to access contraceptives, FGD participants reported that they received detailed information from providers especially at public health facilities and CBDs unlike the drug shop operators. The CBDs were appreciated even more for the quality time and response to clients concerns. There were also some gaps noted by the participants in regards to counselling of clients for contraceptives. These included; lack of privacy during counselling, limited counselling tailored to the available contraceptive options and minimal counselling to the returning clients:

'The first time I went to a CBD for depo, I was counselled for over 30 minutes but the subsequent visits I just go for the injection and within five minutes, I am done'. Female participant, FGD 4

Participants reported that CBDs and DSOs had good customer care towards their clients. Majority mentioned that these two providers were welcoming and sociable compared to the health care workers at public health facilities, who are unkind and always attend to clients hurriedly. One participant noted:

'The client turn up at the public health facility is high...the health workers cannot get time to talk to each client alone but the CBDs work on few clients and take a lot of time with them discussing the available methods'. Female respondent, FGD 4

Participants mentioned mechanisms for contraception continuity such as provision of client cards to remind clients on return dates, follow up visits by CBDs and referrals linkages to each other (the providers). Participants explained that CBDs referred them to the government health centres for contraceptives in case they lacked commodities. Also in situations of severe side effects, the other providers all referred their clients to nearby public health facilities. In regards to client follow-up, CBDs were positioned highly by the current users of contraceptives:

‘Even if I forget to check my return date on the client card, my provider (CBD) reminds me because she is in the same neighbourhood’. Female participant, FGD 3

The issue of providing contraceptives in the context of other services came out boldly especially among the two FGDs of current users of contraceptives. Participants appreciated that government health centres had a collection of services under the same roof compared to the other providers. They mentioned going for services such as HIV counselling and testing, immunization and circumcision in addition to contraceptives. One participant remarked:

'I started using contraceptives when my baby was still very young because I was counselled for family planning when I had taken my baby for immunization at Masafu Hospital'. Female participant, FGD 2

Provider’s perspectives on the existence of family planning guidelines: Very few providers knew that family planning guidelines existed. They were also not certain on what the guidelines said on use of contraceptives by youths (15-24 years). There was also uncertainty across all providers interviewed on whether there were some methods prohibited from being used by the youths:

‘May be there guidelines somewhere but I am not familiar with what exactly they say about family planning use by youths’. Drug Shop Operator 2

Providers’ perspectives on availability and types contraceptives dispensed to young people: The main methods provided by all providers included; oral contraceptive pills, condoms, and Depo-Provera. All providers mentioned that they referred their clients to each other in-case of stock outs however referrals for public health providers were limited within their system. Provision of contraceptives was open throughout the opening hours. Public health facility providers and CBDs also reported frequent stock outs of contraceptives. By the time of this research, they reported a stock out of Depo-Provera that had lasted for three months (April, May and June). The providers except DSOs mentioned that they were supplied with very few commodities.

‘The family planning commodities we receive every quarter at this health facility are very few and yet we share them with all the CBDs attached to this facility.... they run out a few weeks after supply’. Midwife 2

Further probing showed that even where contraceptives were available, certain situations such as provider bias and the cost of the services limited youths to access contraceptives. Some providers reported dispensing only condoms to youths and denying the other methods especially the injectable contraceptive for the unmarried. This was justified on several grounds such as appropriateness for the youths or unmarried, and some providers believed that youths required medical examination from big health facilities. The cost of service also limited access to contraceptives by youths. Some public health providers and CBDs asked for money for the service yet contraceptives were meant to be for free.

Providers’ perspectives on demand for contraceptives among youths: When asked about the availability of demand for contraceptives among the youths 15-24 years in their communities, all providers believed the demand was there. Providers mentioned that the demand was growing because of the community mobilisation by CBDs. Other factors that influenced the demand were; burden of looking after a big family, perceived benefits of contraceptives, contraceptive knowledge, fear of consequences of unwanted pregnancies, and parental influence. Teenage pregnancy was also noted to be common in the study community, an indication of the need for contraceptives among youths. On the other hand, providers mentioned some factors that constrained the demand for contraceptives among the youths. These included; misconceptions and fears, lack of partner’s support and health service barriers:

‘In our community people still have a belief that if one started using family planning before child birth, they may fail to deliver in future’. CBD 1

Providers’ perspectives on contraceptive use by youths: Generally, almost all providers interviewed supported use of contraceptives by youths although when probed in-depth, sentiments of bias come out. The providers mentioned that contraceptives helped the youths to prevent sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancies and avoid dropping out from school. Some providers had reservations based on youth’s ability to properly use of contraceptives and the likelihood of youths living irresponsibly because they are protected against pregnancy.

‘My worry is that youths may start living carelessly because contraceptives give them protection against pregnancies, which is their biggest fear’. Drug Shop Operator 2

Majority of the providers believed youths in school or the unmarried shouldn’t be seeking contraceptives but first finish school, avoid sexual relationships or be very careful in their relationships. On the other hand some providers believed youths in school should use only condoms. Some providers felt that contraceptive use among youths should be restricted to certain emergency situations. For instance one provider said that youths should only be given emergency contraceptive pills and only in cases of rape or condom burst. In addition, side effects of contraceptives, inconsistent use and poor continuance were cited as reasons for not giving youths contraceptives (especially the unmarried and school going youths).

Refusal to provide contraceptives to youths: Half of the providers interviewed reported ever denying a youth contraceptive services during their service. And although the other half never reported having refused to deliver contraceptive services to youths, some mentioned that at least they had referred them to other providers:

‘I have once refused to sell condoms to a young boy. That boy was too young...I was not sure the condom would even fit him’. DSO 1

Norms affecting distribution of contraceptives to youths: The providers mentioned that some of their religious norms did not agree with use of modern contraceptives but instead supported use of natural contraception. This did not only apply to youths but to everybody and it was the Catholics who were affected. The providers also mentioned that youths in their communities still had strong socio reservations on use of contraceptives:

‘We do dispense contraceptives to even the youths but given the perceptions that our community still hold against use of contraceptives by youths, you see the youths coming for services in hiding’ . CBD 2

Discussion

Overall, our results show a number of gaps in relation to the quality of available contraceptive services to the youths. The gaps include; inconsistencies in the supply of contraceptives, limited contraceptive options, absence of counselling from some contraceptive providers and perceived technical incompetency among some contraceptive providers. We also found that, providers had misconceptions about contraceptive use among youths and negative attitudes towards provision of contraceptives to the young ones and unmarried youths.

Evidence from various settings suggests that receiving good quality contraceptive services encourages acceptance and continuation of contraceptive use [30]. However, this study showed perceived gaps in the quality of the existing contraceptive services received by youths. Youths reported limited contraceptive options, inconsistent supply of contraceptives, absence of counselling from drug shop operators, perceived technical incompetency among some contraceptive providers and limited mechanisms for continuity. These gaps are indicative of the difficulties youths experience in receiving modern contraceptives as well as reasons for the low uptake and inconsistent use of contraceptives among this age group despite a conducive policy environment [31].

It is evident that reproductive health services for young people are available in the maternity health facilities but the intimidating nature of the health facilities and negative attitudes of staff make these services practically unavailable to unmarried women [32]. Indeed, in this study, the participants reported that even when the contraceptives were available at the government health centres, youths often missed the services because the health workers were too busy to attend to them. The participants further noted that they preferred contraceptive services from CBDs and DSOs because unlike the government health workers who are unkind and always attend to clients hurriedly, the CBDs and DSOs have good customer care towards their clients. The poor attitude of government health workers towards clients could be explained by the fact that government health workers are often burdened with the heavy workloads at the facilities. This may therefore imply that in order to deliver youth friendly contraceptive services, these services should be provided outside a hospital setting.

The participants also aired out their concerns about receiving contraceptive services from drug shop operators who often not trained, lacked experience and sometimes administered wrong or expired methods to the clients. The lack of training and experience by service providers creates a perfect storm hindering quality of contraceptive service delivery among youth [33]. Therefore, in order to ensure quality of contraceptive services provided to the youth, adequate training, supervision and mentorship should be provided to all service providers.

It is significant to understand contraceptive providers’ perspectives toward distributing contraceptives to youths. This is because provider's perspective in family planning delivery has an important component in effective provision and usage of family planning [34, 35]. As such, this study also explored the perceptions of different family planning providers on the provision of contraceptives to youths. This study showed a few positive provider perceptions towards dispensing contraceptives to young people and substantial concealed biases driving service delivery practices. For example, providers in this study revealed exclusionary practices based on age or marital status, as has been documented elsewhere in Africa [36]. However as shown by Estelle et al, restrictions are more likely to be based on age compared to marital status [37, 38]. Previous research using mystery clients in Nigeria showed that adolescents experienced negative and judgmental attitudesand were sometimes counselled on moral matters rather than contraceptive methods when trying to access family planning services [36, 39]. Likewise in our study, providers universally reported counselling the youths and unmarried people on abstinence from sex rather than on contraceptive methods when they sought contraceptive services. Another study in Uganda revealed that providers believed that contraceptives would cause infertility, thereby influencing provider restrictions and behaviours [14]. In the same manner, some providers in this study believed that if contraception was started too early or before childbirth would lead to delayed fertility or to the worst, infertility. The provider's health and safety concerns, especially regarding unmarried youths and those without children, resulted in hesitation in providing contraceptives. This finding highlight gaps in provider knowledge on contraception and the influence of providers’ personal beliefs on service provision to young people.

This study highlights several program and policy implications. To begin with, gaps in providers' knowledge and competence need to be addressed immediately in order to improve on how providers serve youths so as to meet the individual needs of different groups of youths. In addition, youths should be well informed about and have access to a variety of contraceptives. There is also need for family planning programmers to harmonize the existing family planning training materials for knowledge uniformity across providers. Furthermore, as a standard practice, all family planning training materials should have a section on youths just as it is with other vulnerable groups like people living with HIV/ AIDS. Still on capacity building, this study has shown a wider gap in knowledge and skills between DSOs and the rest of the providers in spite of youths having a positive perspective of their client relations. Although in Uganda, drug shops are not accredited to provide injectable contraceptives, the reality is that drug shops particularly in rural communities play an important role in providing contraceptive services and their potential to reach youths should not be overlooked. Therefore capacity building interventions are needed to target drug shop operators for the safety of their clients. This should be followed by processes of revisiting Uganda's regulatory and policy environment on drug shop services, after all evidence shows that even Village Health Team members with limited training, can safely administer the injectable contraceptive [36]. Lastly, health systems need to disseminate policy guidelines beyond facility based providers such that both public and private sectors providers are familiar with service delivery policy guidelines and thus quality and uniformity in service delivery.

Our study was limited by the fact that we never conducted exit interview with clients and therefore the recall bias might have had an impact on the study results. However, the findings can provide insight into how contraceptive service delivery to young people can be improved in similar rural settings.

Conclusion

The study showed uneven availability of contraceptive supplies and limited information characterized the contraceptive services accessed by youths. In addition, the providers had negative attitudes towards dispensing contraceptives to the unmarried and in-school youths. Therefore, to improve contraceptive uptake among youths; availability of contraceptive choices should not be compromised; providers should be trained in how to serve youths; and dispensing contraceptives should be accompanied by adequate information.

Acknowledgement

The authors are indebted to all the study participants. We are also indebted to Dr. Rhoda Wanyenze, Dr. Joseph Matovu and Dr. Angela Akol who reviewed and provided comments on the manuscript before submission. The work described in this article was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 5U2GPS000971-05 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Hubacher D, Mavranezouli I, McGinn E. Unintended pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: magnitude of the problem and potential role of contraceptive implants to alleviate it. Contraception. 2008 Jul;78(1):73-8. PubMed PMID: 18555821.

- Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy and abortion in Uganda. Issues Brief (Alan Guttmacher Inst). 2013 Jan;(2):1-8. PubMed PMID: 23550324.

- Nsubuga H, Sekandi JN, Sempeera H, Makumbi FE. Contraceptive use, knowledge, attitude, perceptions and sexual behavior among female University students in Uganda: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health. 2016 Jan 27;16:6. PubMed PMID: 26818946.

- UBOS I. Uganda demographic and health survey 2011. Kampala and Claverton: Uganda Bureau of Statistics and ICF International Inc. 2012.

- Ma Q, Ono-Kihara M, Cong L, Xu G, Pan X, Zamani S, et al. Early initiation of sexual activity: a risk factor for sexually transmitted diseases, HIV infection, and unwanted pregnancy among university students in China. BMC Public Health. 2009 Apr 22;9:111. PubMed PMID: 19383171.

- Coker AL, Richter DL, Valois RF, McKeown RE, Garrison CZ, Vincent ML. Correlates and consequences of early initiation of sexual intercourse. J Sch Health. 1994 Nov;64(9):372-7. PubMed PMID: 7877279.

- Dixon-Mueller R. Starting young: Sexual initiation and HIV prevention in early adolescence. AIDS Behav. 2009 Feb;13(1):100-9. PubMed PMID: 18389362.

- Machel JZ. Unsafe sexual behaviour among schoolgirls in Mozambique: a matter of gender and class. Reprod Health Matters. 2001 May;9(17):82-90. PubMed PMID: 11468850.

- Magadi M. Poor pregnancy outcomes among adolecents in South Nyanza Region of Kenya. Afr J Reprod Health. 2006 Apr;10(1):26-38. PubMed PMID: 16999192.

- Hancock NL, Stuart GS, Tang JH, Chibwesha CJ, Stringer JS, Chi BH. Renewing focus on family planning service quality globally. Contracept Reprod Med. 2016 Jun 22;1:10. PubMed PMID: 29201399.

- Campbell OM, Graham WJ, Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 2006 Oct 7;368(9543):1284-99. PubMed PMID: 17027735.

- MOH: The National Policy Guidelines for Sexual and Reproductive Health Services. Ministry of Health (MOH), 2006:19-34.

- MOH M of HK Uganda. Uganda Family Planning Costed Implementation Plan, 2015–2020. 2014.

- Nalwadda G, Mirembe F, Tumwesigye NM, Byamugisha J, Faxelid E. Constraints and prospects for contraceptive service provision to young people in Uganda: providers' perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011 Sep 17;11:220. PubMed PMID: 21923927.

- SEDC. Process Evaluation of GOU Uganda Family Planning Programs and Policies to Design Robust Impact Evaluations: Increasing Demand through Male Involvement and Promotion among Young People. 2016.

- Rutenberg N, Watkins SC. The buzz outside the clinics: conversations and contraception in Nyanza Province, Kenya. Stud Fam Plann. 1997 Dec;28(4):290-307. PubMed PMID: 9431650.

- Mroz TA, Bollen KA, Speizer IS, Mancini DJ. Quality, accessibility, and contraceptive use in rural Tanzania. Demography. 1999 Feb;36(1):23-40. PubMed PMID: 10036591.

- Koenig MA, Hossain MB, Whittaker M. The influence of quality of care upon contraceptive use in rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plann. 1997 Dec;28(4):278-89. PubMed PMID: 9431649.

- RamaRao S, Lacuesta M, Costello M, Pangolibay B, Jones H. The link between quality of care and contraceptive use. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2003 Jun;29(2):76-83. PubMed PMID: 12783771.

- Williams T, Schutt-Aine J, Cuca Y. Measuring family planning service quality through client satisfaction exit interviews. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health.. 2000 Jun 1:63-71.

- Newmann SJ, Mishra K, Onono M, Bukusi EA, et al. Providers’ perspectives on provision of family planning to HIV-positive individuals in HIV care in Nyanza Province, Kenya. AIDS Res Treat. 2013;2013:915923. PubMed PMID: 23738058.

- UBOS UB of SK Uganda. Demographic and Health Survey. Key Indicators Report Uganda. 2016.

- Kakaire O, Kaye DK, Osinde MO. Contraception among persons living HIV with infection attending an HIV care and support centre in Kabale, Uganda. J. Public Health Epidemiol. 2010 Nov 30;2(8):180-8.

- Nalwadda G, Mirembe F, Byamugisha J, Faxelid E. Persistent high fertility in Uganda: young people recount obstacles and enabling factors to use of contraceptives. BMC Public Health. 2010 Sep 3;10:530. PubMed PMID: 20813069.

- Lutalo T, Kigozi G, Kimera E, Serwadda D, Wawer MJ, et al. A randomized community trial of enhanced family planning outreach in Rakai, Uganda. Stud Fam Plann. 2010 Mar;41(1):55-60. PubMed PMID: 21465722.

- Bruce J. Fundamental elements of the quality of care: a simple framework. Stud Fam Plann. 1990 Mar-Apr;21(2):61-91. PubMed PMID: 2191476.

- Busia District Annual Health Report. Busia district health department. 2011.

- Godlee F, Jefferson T, editors. Peer review in health sciences. London: BMJ Books; 2003 Jan.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004 Feb;24(2):105-12. PubMed PMID: 14769454.

- Polis CB, Gray RH, Lutalo T, Nalugoda F, Kagaayi J, et al. Trends and correlates of hormonal contraceptive use among HIV-infected women in Rakai, Uganda, 1994 2006. Contraception. 2011 Jun 1;83(6):549-55. PubMed PMID: 21570553.

- MOH M of HK Uganda. The National Policy Guidelines for Sexual and Reproductive Health Services. Ministry of Health (MOH); 2006.

- Amanda P. Strengthening PreService Education for Family Planning Services in sub-Saharan Africa. 2013.

- Paine K, Thorogood M, Wellings K. The impact of the quality of family planning services on safe and effective contraceptive use: a systematic literature review. Hum Fertil. 2000;3(3):186-193. PubMed PMID: 11844376.

- Shelton JD. The provider perspective: human after all. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2001 Sep 1;27(3):152-61.

- Adekunle AO, Arowojolu AO, Adedimeji AA, Roberts OA. Adolescent contraception: survey of attitudes and practice of health professionals. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2000;29(3-4):247-252.

- Stanback J, Mbonye AK, Bekiita M. Contraceptive injections by community health workers in Uganda: a nonrandomized community trial. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(10):768–773. PubMed PMID: 18038058.

- Sidze EM, Lardoux S, Speizer IS, Faye CM, Mutua MM, Badji F. Young women’s access to and use of contraceptives: the role of providers’ restrictions in Urban Senegal. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;40(4):176-183. PubMed PMID: 25565345.

- Sidze EM, Lardoux S, Speizer IS, Faye CM, Mutua MM, Badji F. Young women's access to and use of contraceptives: the role of providers' restrictions in Urban Senegal. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014 Dec;40(4):176-83. PubMed PMID: 25565345.

- Olowu F. Quality and costs of family planning as elicited by an adolescent mystery client trial in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 1998;2(1):49–60. PubMed PMID: 10214429.