Trichotillomania of Eyelashes: An Uncommon Disorder

El Jouari O1*, Zaougui AA2, Gallouj S1, Senhaji G1, Farih MH2, Mernissi FZ1

1 Department of Dermatology University Hospital Hassan II, Fez, Morocco.

2 Department of Urology University Hospital Hassan II, Fez, Morocco.

*Corresponding Author

Ouiame EL Jouari,

Department of Dermatologym,

University Hospital Hassan II, Fez, Morocco.

Tel: 212645768798

Fax: 212535617687

E-mail: eljouariouiame@gmail.com

Received: June 12, 2018; Accepted: July 19, 2018; Published: July 23, 2018

Citation: El Jouari O, Zaougui AA, Gallouj S, Senhaji G, Farih MH, Mernissi FZ. Trichotillomania of Eyelashes: An Uncommon Disorder. Int J Pediat Health Care Adv. 2018;5(3):81-83. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2572-7354-1800022

Copyright: El Jouari O© 2018. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Trichotillomania is a disorder characterized by the noncosmetic, repetitive pulling of hair from any part of one's body, resulting in noticeable hair loss or alopecia. It is included under anxiety disorders because it shares some obsessive-compulsive features. We report a particular case of a 12-year-old girl with one-year history of secondary enuresis, referred by his urologist for the management of an isolated alopecia of the eyelashes.

2.Introduction

3.Case Presentation

4.Discussion

5.Conclusion

6.References

Keywords

Trichotillomania; Eyelashes; Dermoscopy; Behavior Therapy.

Introduction

Trichotillomania is an impulse control disorder characterized by chronic hair-pulling, distress, and impairment [1]. It is a neglected psychiatric disorder with dermatologic expression that has only recently received research attention. We report the case of an isolated alopecia of the eyelashes in a 12-year-old girl.

Case Presentation

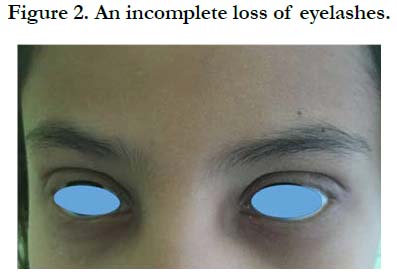

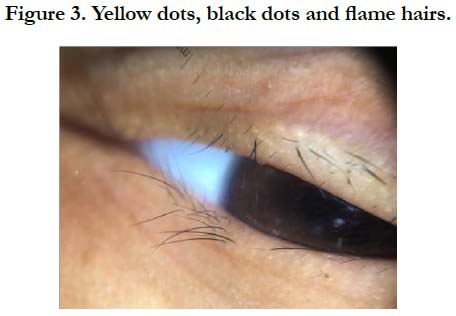

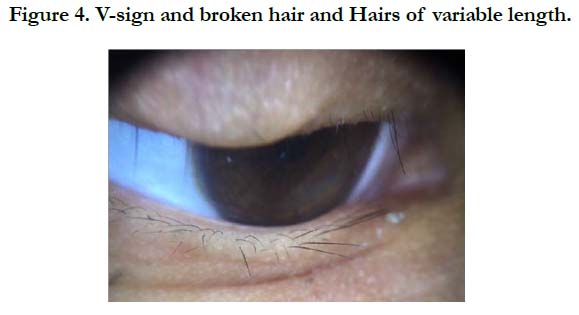

A 12-year-old girl with one-year history of secondary enuresis, referred by his urologist for the management of an eyelash loss. She had no family history of mental illness and a normal developmental history. She lived with her parents and a five-yearold sister. The family was not socially disadvantaged and there was no marital conflict. Trichotillomania started suddenly 8 months after a failure in school when child pulled out all her eyelashes. The clinical examination found an incomplete depilation of the eyelashes of the both eyes, without inflammation, desquamation or scaring (Figures 1, 2). The hair pull test was negative. The trichoscopy objectified Yellow dots, black dots, broken hair, flame hairs, V-sign and Hairs of variable length (Figure 3,4) in favor of trichotillomania. The diagnosis of pediatric trichotillomania was made and this was explained to her parents. Laboratory tests were negative. We referred the girl for ophthalmologic and psychological examination. Ophthalmologic examination proved that there was no eye damage. After consultation with the psychiatrist, we started treatment with cognitive behavioral therapy and lash Strengthening gel. With parent's cooperation, the treatment was successful.

Discussion

The name trichotillomania was first employed by the French dermatologist Francois Henri Hallopeau in 1889. The word is derived from the Greek thrix (hair), tillein (to pull), and mania (madness) [1]. Trichotillomania is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as an impulse control disorder, similar to kleptomania, pyromania, or compulsive skin picking [3]. The disorder is included under anxiety disorders because it shares some obsessive-compulsive features. Patients have the tendency towards feelings of unattractiveness, body dissatisfaction, and low self-esteem [4]. The prevalence of pediatric trichotillomania is estimated of approximately 0.5% and it is up to seven times more common in children than in adults [3].

The DSM-IV-TR requires five criteria for the disorder to be diagnosed: (a) one intentionally and repetitively pulls out his or her hair, resulting in noticeable hair loss; (b) an increasing sense of tension occurs immediately before or when trying to resist pulling; (c) pleasure, gratification, or relief occurs once the hair is pulled; (d) another mental or medical condition does not better account for the behavior; and (e) the behavior causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning [3]. Trichoscopic features observed are broken hairs of different lengths, trichoptilosis, V-sign (two broken hairs at the same length emerging from the same follicle), and flame hairs which occurred exclusively in trichotillomania, related to mechanical trauma and hairshaft fractures from shearing force [5]. The management of the disease is difficult and requires strong cooperation between the physician, patient, and parents [6]. It depends on the age of the child; several treatment options are available to combat trichotilomania [1]. Behavior therapy, hypnosis, insight-oriented psychotherapy, and pharmacologic therapy have been considered. No treatment approach has been established as effective in a large controlled trial [2]. These children and their parents may not be aware of the cause of their affliction or may feel helpless to change their pulling behavior [1]. They should view relapses as learning opportunities that allow identification of triggers and barriers to successful behavior change [3]. Most parents and children will be relieved to hear that there is no physical problem and that the hair will eventually grow back normally with the implementation of minimally invasive behavioral treatments [3].

Conclusion

Trichotillomania is an increasingly common disorder, causing overt alopecia on the affected part of the body. Isolated involvement of the eyelashes is rare. The hair pull test and the dermoscopy guide the diagnosis and eliminate alopecia areata.

References

- Harrison JP, Franklin ME. Pediatric trichotillomania. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012 Jun;14(3):188-96. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0269-8. PubMed PMID: 22437627.

- Hautmann G, Hercogova J, Lotti T. Trichotillomania. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002 Jun;46(6):807-21. PubMed PMID: 12063477.

- Labouliere CD, Storch EA. Pediatric trichotillomania: Clinical presentation, treatment, and implications for nursing professionals. J Pediatr Nurs. 2012 Jun;27(3):225-32. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2011.01.028. PubMed PMID: 22525810.

- Zimova J, Zimova P. Trichotillomania: bizzare patern of hair loss at 11-yearold girl. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2016 Jun;24(2):150-3. PubMed PMID: 27477178.

- Khunkhet S, Vachiramon V, Suchonwanit P. Trichoscopic clues for diagnosis of alopecia areata and trichotillomania in Asians. Int J Dermatol. 2017 Feb;56(2):161-165. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13453. PubMed PMID: 28074524.

- Morris SH, Kratz HE, Burke DA, Zickgraf HF, Coogan C, Woods D, et al. Behavior therapy for pediatric trichotillomania: Rationale and methods for a randomized controlled trial. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2016 Apr 1;9:116-24.