Is Helicobacter Pylori Associated with a Migraine?

Ali Abdelrazak M1*, Mahmoud Mohamed A2, Ali Radwa A3

1 Professor of Pediatrics, International Islamic Center for Population Studies & Research. Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt.

2 Consultant of Hospital management and Medical Quality Control, Egypt.

3 Researcher Assistant, University of Maryland, College Park, USA.

*Corresponding Author

Abdelrazak Mansour M Ali,

Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine,

Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt.

Tel: 15713317055

E-mail: abdelrazak_ali@yahoo.com

Received: August 24, 2017; Accepted: October 11, 2017; Published: October 13, 2017

Citation: Ali Abdelrazak M, Mahmoud Mohamed A, Ali Radwa A. Is Helicobacter Pylori Associated with a Migraine?. Int J Pediat Health Care Adv. 2017;4(6):55-58. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2572-7354-1700016

Copyright: Ali Abdelrazak M© 2017. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Objective: To determine whether Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is associated with migraine headache.

Design: Case-control study.

Settings: Local tertiary Hospitals in Cairo, Egypt and in HaferAlbaten, Saudi Arabia.

Participants:A total of 70 patients with migraine who were 7 to 17 years old and who fulfilled the International Headache Society criteria for migraine and a total of 50 controls without migraine who were matched by the country of origin, age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status to the 70 migraine cases.

Main Outcome Measures: Antibody levels to H. pylori (IgG) and H. pylori stool antigens were compared between the two groups.

Results: Significant association was found between H. pylori and migraine and of the total of 70 migraineur cases, 55.7% were positive for H. pylori stool antigen testing compared to 20% in control group (P value=0.0002). Joint pain was reported in 44.3% and 18.0% of cases and controls respectively (P value=0.0034).

Conclusion: H. pylori is associated with migraine without aura and may be a causative factor. Moreover, H. pylori may induce joint pain in the migraineur patients.

2.Methods

3.Results

4.Discussion

5.Conclusion

6.References

Background

Helicobacter pylori (Hp) is a gram-negative bacillus responsible for one of the most common infections found in humans worldwide, with more than 50% of the world’s population infected, especially in developing countries where those chronically infected can reach up to 90% by adulthood [1]. Children differ from adults with respect to H. pylori infection in terms of the prevalence of infection, the complication rate, the near-absence of gastric malignancies, age-specific problems with diagnostic tests and drugs, and a higher rate of antibiotic resistance. These and other differences explain why some of the recommendations for adults may not apply to children [2]. Unless treated, colonization usually persists lifelong and H. pylori infection represents a key factor in the etiology of various gastrointestinal diseases [3]. Since H. pylori is non-invasive and the infection is accompanied by an exuberant humoral response, one might predict that T helper cell 2(Th2) response would be predominant within H. pylori-colonized gastric mucosa. Paradoxically, most of H. pylori antigen specific T-cell clones isolated from infected gastric mucosa produce higher levels of IFN-γ than IL-4, which is reflective of a T helper (Th1)-type response [4]. H. pylori also stimulates production of IL-12 in vitro, a cytokine that promotes Th1 differentiation. These findings raise the hypothesis that an aberrant host response (Th1) to an organism predicted to induce secretory (Th2) immune responses may influence and perpetuate gastric inflammation [5].

Urease and motility using flagella are essential factors for its colonization. Urease of H. pylori exists both on the surface and in the cytoplasm, and is involved in neutralizing gastric acid and in chemotactic motility [6]. H. pylori infection has been clearly linked to peptic ulcer disease and some gastrointestinal malignancies. Increasing evidence demonstrates possible associations to disease states in other organ systems, known as the extra intestinal manifestations of H. pylori [7].

In the recent years, the role of infections and the impact of digestive system disorders on migraine have gained more attention. However, in the last few years, researches have focused on the role of Helicobacter pylori activity in the pathogenesis of migraine.

Frequent or severe headaches, including migraine, have been reported in 17% of children and adolescents, and the prevalence of headache in general increases from childhood to adolescence, with an increase in the proportion of tension-type headaches from the early teen years [8]. Migraine is divided into two main categories: migraine with aura, in which patients experience transient visual or sensory symptoms (including flickering lights, spots, or pins that develop 5-20 minutes before attacks), and migraine without aura [9, 10].

H. pylori infection causes a persistent activation of the immune system, which results in local and systemic release of a variety of vasoactive substances. Recent evidence suggest that infection with H. pylori may also be associated with migraine [11]. Several mechanisms such as inflammation, pain mediators such as calcitonin-gene-related peptide (CGRP), and neurotransmitters such as serotonin [11, 12] are currently discussed; indeed, serotonin agonists such as triptans can relieve migraine, and selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants have been used successfully as prophylactic treatments [12]. A research explained that gastrointestinal neuroendocrine cells such as enterochromaffin cells (EC cells) can synthesize and secrete serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) and some factors that motivate the cell to secrete 5-HT can cause central nervous system (CNS) perturbation via the brain-gut axis, which can demonstrate that most patients with migraine assaults are associated with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms [13]. Inflammation motivates the cell to secrete 5-HT e.g., when H. pylori infect a cell. Eradication of H. pylori infection has helpful outcomes to improve clinical attacks [14-17]. This was attributed to the effect of eradication therapy on the inflammation induced high levels of 5-HT [17, 18].

Among patients with migraines, different studies have shown increased prevalence of H. pylori infection as determined by positive urea breath test [19, 20]. Similarly, using serology, H. pylori IgG positivity was found to be higher in those with migraines compared to matched controls [21].

Methods

Methods Approval of this study was received from the administrations of the Hospitals in which the study was conducted in. The routine consents for laboratory diagnosis were implemented for all cases according to Hospital regulations, and the study protocol conforms to the Ethical Guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Children were recruited through primary care physician offices and Nor-khan General Hospital (Hafer Al Batin, Saudi Arabia) as well as Al-Azhar University Hospitals Cairo, Egypt. All participants between 7 years and 17 were investigated for H. pylori using two laboratory tests. (H. pylori IgG and H. pylori stool antigen).

This case-control study enrolled 70 patients of migraine without aura whose severity was assessed by experienced neurologist and according to the International Headache Society criteria [Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society] [22].

The inclusion criteria for the patients were age between 7 and 17 years, without gastrointestinal symptoms (such as epigastric pain, belching, bloating) or receiving any nonstandard medication or any treatment for H. pylori.

Controls were 50 randomly selected from non-migraines patients referring to the Hospitals at the about same time as cases. Group matching was done according to age, sex, educational level, geographical origin, and socio-demographic status. Required data including age, sex, gastro-intestinal (GI) disorder, history of infant colic, history of migraine in family, degree of headache and sleep disorder was obtained from all the people in the case and control groups by interviewing and completing a questionnaire. The antibody (immunoglobulin G-IgG) titer of all individuals in the case and control groups (against H. pylori) was assessed by Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). It is noteworthy that the geographic distributions of eligible participating children add more strength to the design of our study.

Additionally, the H. pylori stool antigen testing was done for all participants. This one-step test is a chromatographic immune assay for the qualitative detection of H. pylori infections (Alcon Laboratories Inc.). It is a relatively simple, reliable, more applicable, and non-invasive test of H. pylori infections in children. H. pylori fecal antigen has shown a high degree of sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values [23].

IgG is much more specific in children than adults, affirming the fact that adults are more likely to have been exposed to H. pylori in the past [24, 25]. IgM was not implemented for investigation as it has been found to have little diagnostic utility for H. pylori infections and is elevated only acutely after infection, whereas H. pylori infections are generally chronic [26].

Statistical software SPSS for Windows (version 18.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical calculations. Associations between H. pylori antibodies and severity of headache were estimated using Pearson correlation coefficient. P ≤ 0.050 was considered in all tests as a significant level. The demographic characteristics of cases and controls were compared using the Fisher exact test, and odds Ratio.

Results

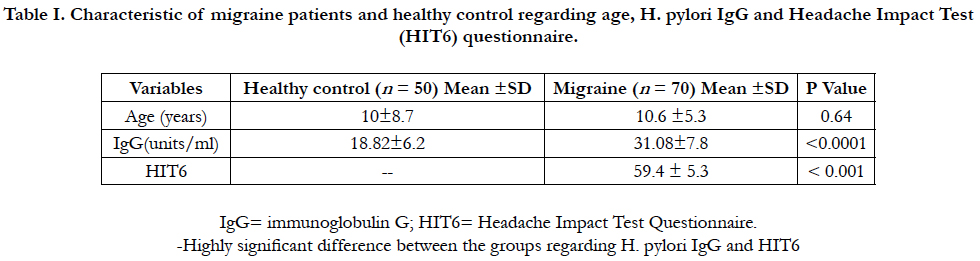

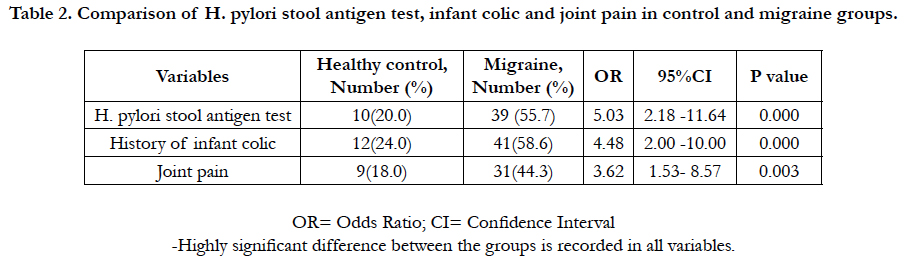

Among the 120 enrolled participants, there was homogeneous distribution in both groups regarding to age, sex, race, family size, insurance status, and education. In migraine cases, there were 37 girls (52.9%) and 33 boys (47.1). In control, the enrolled girls and boys were 54% and 46% respectively. The mean age was (10.6 ±5.3) and (10±8.7) years for case and control groups respectively. H. pylori IgG was 31.08 ± 7.8 and 18.82 ± 6.2 in case and control groups respectively, 95% CI = -14.90 to -9.63, P value < 0.0001 (Table 1). Of the total 70 migraine cases, 39 cases (55.7%) tested positive H. pylori stool antigen compared to 10 controls (20%). OR=5.03, 95% CI = 2.18 to 11.64, P value = 0.0002. History of infant colic was reported in 58.6% of cases compared to 24.0% in control (OR=4.48, 95%CI=2.00-10.00, P value=0.0003). Joint pain was 44.3% compared to18.0% in control (OR= 3.62, 95% CI=1.53 to 8.57, P value=0.0034).

Table I. Characteristic of migraine patients and healthy control regarding age, H. pylori IgG and Headache Impact Test (HIT6) questionnaire.

Table 2. Comparison of H. pylori stool antigen test, infant colic and joint pain in control and migraine groups.

Discussion

There has been a recent surge of research evaluating the increased evidence of possible associations of H. pylori to disease states in other organ systems, known as the extraintestinal manifestations of H. pylori. Different conditions associated with H. pylori infection include those from hematologic, cardiopulmonary, metabolic, neurologic, and dermatologic systems. The aim of this study is to provide a concise evidence, if any that supports the associations of H. pylori and migraine headache. There is a complex interplay between certain unique players that is the complex combination of environmental, host, and bacterial factors which ultimately determines the susceptibility and severity of outcome of H. pylori infection. Based on the literature review, this is the first study attempting to find a correlation between the severity of headache (in terms of HIT6) in one side and H. pylori antibody levels and H. pylori antigens in migraineur’s children without aura in the other side. As there is a prominent variation in the prevalence of H. pylori infection, also there is parallel variation in the prevalence of migraine. The connection between the brain and the gastrointestinal system is imperative to the regulation of the digestive tract and its immune system.

The results of this study suggest that the relationship between migraine and H. pylori infection is a complex one, at least in this clinical sample of children referred for H. pylori testing. The genetic diversity of H. pylori and the variations in human host response to the microorganism underlie the complex hostpathogen relationship that determines the outcome of infection. Our study results concord with a recent meta-analysis study reported that a total of five case-control studies, showed that H. pylori infection is indeed a risk factor for migraine [27]. These studies recruited patients who mainly suffered from migraine without aura because this subtype of migraine seems to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, whereas migraine with aura is probably determined largely, or exclusively, by genetic factors [28, 29]. It has been suggested that the pathogenic role of the H. pylori infection in migraine, is based on a relationship between the host immune response against the bacterium and the chronic release of vasoactive substances. Postulated factors of the relationship between migraine and H. pylori infection included inflammation, oxidative stress, and nitric oxide imbalance [16, 30, 31]. During the infection, the bacterium releases toxins in the infected tissue, thus promoting the special cascade of events related to the host immune response alterations of vascular permeability [16, 32]. Therefore, the prolonged oxidative injury caused by the persistent infection and the release of vasoactive substances might be involved in local cerebral blood circulation changes during migraine attacks [33].

The results show that the level of H. pylori IgG is correlated with the migraine severity and this could be explained by the study of Asghar et al., that reported relationship between the host immune response against the H. pylori infection and the chronic release of vasoactive substances [34]. This is logically interpreted if considering the chronic inflammation that is perpetuated by H. pylori infection. It has recently been demonstrated that only microbial stimuli characterized by the induction of TLR (toll-like Receptor) activation and Th1 responses can activate natural killer cells, which then assist in the initiation of this type-1 response [35]. As a result, the extent of bacterial infection coincides with the severity and progression of the migraine headache. It is the level of stimulation which induces T helper cells differentiation into cells expressing either Th1 cytokine or Th2 cytokine phenotype [36]. Consequently, development of migraine in subset of individuals is characterized by the Th1 induced high level of microbial stimulation.

Our results reveal correlation between migraine and history of infant colic. This correlation might be explained by the studies of Sillanpaa [37] and Romanelli et al., [38]. The authors postulated a molecular link between these two conditions in the form of Calcitonin gene-related peptide “CGRP” which is released during migraine attacks and is potentially also involved in the pathogenesis of abdominal pain by causing inflammation of sensory GI neurons. Additionally, our results recovered relationship between migraine and joint pains, this could be interpreted in the light of the CGRP induced synovitis, where it was found that CGRP contributes to transition from normal to persistent synovitis, and the progression from nociception to sensitization [39]. Also, CGRP may play a role in pain transmission in somatic pain conditions such as joint and muscular chronic pain [40].

Conclusion

H. pylori is associated with migraine without aura and may be a causative factor. Moreover, H. pylori may be the pathogenetic mechanism of joint pain in susceptible migraineur patients.

References

- Torres J, Lopez L, Lazcano E, Camorlinga M, Flores L, Muñoz O, et al. Trends in H. pylori infection and gastric cancer in Mexico. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005 Aug;14(8):1874-7.

- Hojsak, Iva. Helicobacter pylori Gastritis and Peptic Ulcer Disease. Guandalini S, Dhawan A, Branski D. In: Textbook of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. 2015;143.

- Kusters JG, van Vliet AHM, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter Pylori Infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006 Jul;19(3):449-490. PubMed Central PMID: PMC1539101.

- Bamford KB, Fan X, Crowe SE. et al. Lymphocytes in the human gastric mucosa during Helicobacter pylori have a T helper cell 1 phenotype. Gastroenterology. (1998);114, 482–492. PubMed PMID: 949638.

- Sawai N, Kita M, Kodama T, et al. Role of γ interferon in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammatory responses in a mouse model. Infect. Immun. 1999;67(1):279–285. PubMed PMID: 9864227.

- Yoshiyama H, Nakazawa T. Unique mechanism of Helicobacter pylori for colonizing the gastric mucus. Microbes Infect. 2000 Jan;2(1):55-60. Pub- Med PMID:10717541.

- Wong F, Rayner-Hartley E, Byrne MF. Extra intestinal manifestations of Helicobacter pylori: a concise review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Sep 14;20(34):11950-61. PubMed PMID: 25232230.

- Lateef TM, Merikangas KR, He J, Kalaydjian A, Khoromi S, Knight E, et al. Headache in a national sample of American children: prevalence and comorbidity. J Child Neurol. 2009 May;24(5):536–43. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2794247.

- Diener HC, Kaube H, Limmroth V. A practical guide to the management and prevention of migraine. Drugs. 1998 Nov;56(5):811–24.

- de Vries B, Frants RR, Ferrari MD, van den Maagdenberg AM. Molecular genetics of migraine. Hum Genet. 2009 Jul;126(1):115–32.

- Gasbarrini A, Franceschi F, Gabrielli M, Fiore G, Candelli M, Zocco MA, et al. Helicobacter pylori Infection and Migraine. 2000 Feb;13(2):97-101. doi:10.2165/00023210-200013020-00003

- Van Hemert S, Breedveld AC, Rovers JM, Vermeiden JP, Witteman BJ, Smits MG, et al. Migraine associated with gastrointestinal disorders: review of the literature and clinical implications. Front Neurol. 2014 Nov 21;5:241. PubMed PMID: 25484876.

- Mirsane SA, Shafagh S. Effects of Helicobacter pylori Infection and Western Diet on Migraine. Gene Cell Tissue. 2016 July;3(3):e39212. doi: 10.17795/gct-39212.

- Bakhshipour A, Momeni M, Ramroodi N. Effect of Helicobacter Pylori Treatment on the Number and Severity of Migraine Attacks. ZJRMS. 2012 Aug;14(6):6-8.

- Seyyedmajidi M, Banikarim SA, Ardalan A, Hozhabrossadati SH, Norouzi A, Vafaeimanesh J. Helicobacter pylori and Migraine: Is Eradication of H. pylori Effective in Relief of Migraine Headache? Caspian J Neurol Sci. 2016 Nov;2(4):29–35.

- Faraji F, Zarinfar N, TalaieZanjani A, Morteza A. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on migraine: a randomized, double blind, controlled trial. Pain Phys. 2012 Dec;15(6):495-498. PubMed PMID: 23159967.

- Racke K, Reimann A, Schworer H, Kilbinger H. Regulation of 5-HT release from enterochromaffin cells. Behav Brain Res. 1996;73(1-2):83–7. PubMed: 8788482. PubMed PMID: 8788482.

- Haugen M, Dammen R, Svejda B, Gustafsson BI, Pfragner R, Modlin I, et al. Differential signal pathway activation and 5-HT function: the role of gut enterochromaffin cells as oxygen sensors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012 Nov 15;303(10):G1164–G1173. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3517648. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00027.2012.

- Yiannopoulou KG, Efthymiou A, Karydakis K, Arhimandritis A, Bovaretos N, Tzivras M. Helicobacter pylori infection as an environmental risk factor for migraine without aura. J Headache Pain. 2007 Dec;8(6):329–333. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3476160.

- Gasbarrini A, De Luca A, Fiore G, Franceschi F, Ojetti VV, Torre ES, et al. Primary Headache and Helicobacter Pylori. Int J Angiol. 1998 Aug;7(4):310–312. PubMed PMID: 9716793.

- Hong L, Zhao Y, Han Y, Guo W, Wang J, Li X, et al. Reversal of migraine symptoms by Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in patients with hepatitis-B-related liver cirrhosis. Helicobacter. 2007 Aug;12(4):306-308.

- Bagley CL, Rendas-Baum R, Maglinte GA, Yang M, Varon SF, Lee J, et al. Validating Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire v2.1 in episodic and chronic migraine. Headache. 2012 Mar;52(3):409-21. PubMed PMID: 21929662.

- Konstantopoulos N, Rüssmann H, Tasch C, Sauerwald T, Demmelmair H, Autenrieth I, et al. Evaluation of the Helicobacter pylori stool antigen test (HpSA) for detection of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Mar;96(3):677-83.

- She RC, Wilson AR, Litwin CM. Evaluation of Helicobacter pylori Immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgA and IgM Serologic testing compared to stool antigen Testing. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009 Aug;16(8):1253-55. PubMed PMID: 19515865.

- Harris P, Perez-Perez G, Zylberberg A, Rollán A, Serrano C, Riera F, et al. Relevance of adjusted cut-off values in commercial serological immunoassays for Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Dig Dis Sci. 2005 Nov;50(11):2103-2109. PubMed PMID: 16240223.

- Serrano CA, CG Gonzalez, AR Rollin. Lack of diagnostic utility of specific immunoglobulin M in Helicobacter pylori infection in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008 Nov;47(5):612-617. PubMed PMID: 18979584.

- Su J, Zhou X-Y, Zhang GX. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and migraine: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterology. 2014 Oct 28;20(40):14965-14972. PubMed PMID: 4209561.

- Piane M, Lulli P, Farinelli I, Simeoni S, De et al. Genetics of migraine and pharmacogenomics: some considerations. J Headache Pain. 2007 Dec;8(6):334–339. PubMed Central PMCID: 4209561

- Russell MB, Olesen J. Increased familial risk and evidence of genetic factor in migraine. BMJ. 1995 Aug 26;311(7004):541–544. PubMed PMCID: PMC2550605.

- Ansari B, Basiri K, Meamar R, Chitsaz A, Nematollahi S. Association of Helicobacter pylori antibodies and severity of migraine attack. Iran J Neurol. 2015 Jul 6;14(3):125-129. PubMed Central PMCID: 4662684.

- Francesco F, Giuseppe Z, Roccarina D, Gasbarrini A et al. Clinical effects of Helicobacter pylori outside the stomach. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Apr;11(4):234–242. PubMed PMID: 24345888.

- Negrini R, Savio A, Poiesi C, Appelmelk BJ, Buffoli F, Paterlini A, et al. Antigenic mimicry between Helicobacter pylori and gastric mucosa in the pathogenesis of body atrophic gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1996 Sep;111(3):655–665. PubMed PMID: 8780570.

- Epplein M, Cohen SS, Sonderman JS, Zheng W, Williams SM, Blot WJ, et al. Neighborhood socio-economic characteristics, African ancestry, and Helicobacter pylori sero-prevalence. Cancer Causes Control. 2012 Jun;23(6):897–906. PubMed PMID: 22527167.

- Asghar MS, Hansen AE, Amin FM, van der Geest RJ, Koning Pv, Larsson HB, et al. Evidence for a vascular factor in migraine. Ann Neurol. 2011 Apr; 69(4):635–645. PubMed PMID: 21416486.

- Zannone I, Foti M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Granucci F. TLR-dependent activation stimuli associated with Th1 responses confer NK cell stimulatory capacity to mouse dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2005 Jul 1;175(1):286–92. PubMed PMID: 15972660.

- Rogers PR, Croft M. Peptide dose, affinity, and time of differentiation can contribute to the Th1/Th2 cytokine balance. J Immunol. 1999 Aug 1;163(3):1205–13. PubMed PMID: 10415015.

- Sillanpää M, Saarinen M. Infantile colic associated with childhood migraine: a prospective cohort study. Cephalalgia. 2015 Mar 9;35(14):1246-1251.

- Romanello S, Spiri D, Marcuzzi E, Zanin A, Boizeau P, Riviere S, et al. Association between childhood migraine and history of infantile colic. JAMA. 2013 Apr 17;309(15):1607-1612. PubMed PMID: 23592105.

- Walsh DA, Mapp PI, Kelly S. Calcitonin gene-related peptide in the joint: contributions to pain and inflammation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015 Nov;80(5):965-78. PubMed PMID: 25923821.

- Schou WS, Ashina S, Amin FM, Goadsby PJ, Ashina M. Calcitonin generelated peptide and pain: a systematic review. J Headache Pain. 2017 Dec;18(1):34. PubMed PMID: 28303458.