Effectiveness Of Verbal, Verbal-Written and Video Instructions on Gingival Health of Patients with Fixed Appliances

Cheong Joo Ming1*, Norul Madihah M. Ashaari2, Razan Hayani Mohamad Yusoff2, Siti Marponga Tolos3

1 Department of Orthodontics, Kulliyyah of Dentistry, International Islamic University Malaysia, Jalan Sultan Ahmad Shah, Bandar Indera Mahkota, 25200 Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia.

2 Kulliyyah of Dentistry, International Islamic University Malaysia, Jalan Sultan Ahmad Shah, Bandar Indera Mahkota, 25200 Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia.

3 Department of Computational and Theoretical Sciences, Kulliyyah of Science, International Islamic University Malaysia, Jalan Sultan Ahmad Shah, Bandar Indera Mahkota, 25200 Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia.

*Corresponding Author

Cheong Joo Ming,

Department of Orthodontics, Kulliyyah of Dentistry, International Islamic University Malaysia, Jalan Sultan Ahmad Shah, Bandar Indera Mahkota, 25200 Kuantan, Pahang,

Malaysia.

Tel: +609 5705484

Fax: +609 5705580

E-mail: alvinjooming@iium.edu.my

Received: February 09, 2022; Accepted: April 18, 2022; Published: April 21, 2022

Citation: Cheong Joo Ming, Norul Madihah M. Ashaari, Razan Hayani Mohamad Yusoff, Siti Marponga Tolos. Effectiveness Of Verbal, Verbal-Written and Video Instructions on Gingival Health of Patients with Fixed Appliances. Int J Dentistry Oral Sci. 2022;9(4):5282-5287. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2377-8075-220001058

Copyright: Cheong Joo Ming©2022. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Orthodontic treatment causes detrimental effects on periodontal health due to the accumulation of dental

plaque. This problem can be prevented by implementing effective oral hygiene instructions (OHI).

Aim: Tocompare the effectiveness between verbal, verbal-written and video methods of OHI on the gingival health of patients

with fixed appliances. The best method in providing OHI to patients wearing fixed appliances was also assessed.

Materials and Methods: 39 patients with a mean age of 16.9 wearing upper and lower fixed appliances were divided into

three OHI groups (verbal, verbal-written and video) with five minutes standardized time allocation for each technique. Gingival

health was assessed using plaque index (PI), gingival index (GI), and bleeding on probing (BOP). The mean percentage

difference between pre- and post-OHI was calculated and analysed after 6 weeks. Data were analyzed using paired sample

t-test and one-way ANOVA.

Results: All periodontal parameters showed a reduction in their mean % in all OHI groups after 6 weeks, with significant decrease

in verbal-written and video groups (p<0.05). Verbal group showed significant reduction for PI after 6 weeks (p=0.012).

Overall, there was no significant difference between the effectiveness of the three OHI groups in the mean % reduction of

PI, GI and BOP.

Conclusions: Whilst verbal method was effective in improving the PI, verbal-written and video methods were effective in

improving all aspects of gingival health (PI, GI and BOP) in patients wearing fixed appliances. However, there was no single

best method in delivering OHI to patients with fixed appliances.

2.Introduction

3.Materials and Methods

3.Results

4.Discussion

5.Conclusion

5.References

Keywords

Oral Hygiene; Orthodontic Appliances; Gingival Diseases.

Introduction

A significant increase in the demand of orthodontic treatment

can be seen in recent years due to the growing concern of dental

and smile aesthetics.[1] Although orthodontic treatment improves

dento-facial appearance, it may cause regression of periodontal

health by enhancing the colonization of microorganisms and dental

plaque accumulation. Klukowska et al [2] found that the plaque

coverage in orthodontic patients was two to three times higher

than the levels observed in high plaque-forming adults without

appliances, presumably due tothe various attachments used

in fixed appliances which served as plaque retentive factor that

complicate cleaning. In a study conducted amongst adolescent

patients, the value of periodontal indices increased significantly

during orthodontic treatment, but were not associated with attachment

loss.[3]

Plaque accumulation contributes not only to the inflammation

of periodontal tissues, but may give rise to white spot lesions, decalcification and cavity formation. It is therefore important to

have proper plaque control as a preventive step to eliminate dental

plaque. Oral hygiene instruction (OHI) is proven to benefit the

patients’ oral hygiene significantly by resulting in reduced plaque

score and improved gingival condition.[4]

Verbal, written and video forms are the most common methods

used to give oral hygiene advice in dentistry. [5] All these instructional

methods given professionally by dental professionals improved

gingival conditions to a certain extent. However, there

was not enough evidence to support one method is better than

the other instructional methods. [6, 7] These could be due to

the methodological heterogeneity in these studies; Lee and Rock

(2000) spent thirty minutes for each verbal OHI session, but eight

minutes using video OHI methods.[6] Meanwhile, other studies

limited the assessment of the dental plaque to two third of the

teeth surface only. [8] Furthermore, the incorporation of single

arch assessment only as compared to upper and lower arches

across different studies may made the comparison of OHI methods

difficult.

Thus, the present study aimed to address these shortcomings in

the literature and primarily compared the effectiveness between

verbal, verbal-written and video methods of oral hygiene instruction

on the gingival health of patients with fixed appliances and

to assess the best method in providing oral health instructions to

patients wearing fixed appliances.

Materials And Methods

Study design

This was a prospective study with ethical approval obtained from

IIUM Research Ethics Committee (IREC) [Registration number:

IREC 2019-025].

Subjects

39 patients (31 females, 8 males) from 13 to 22 years old with a

mean age of 16.9 who were undergoing fixed orthodontics treatment

were recruited. Sample recruitment was done from March

2019 to January 2020. Inclusion criteria were patients who have

had extraction or non-extraction treatment and had been fitted

with upper and lower pre-adjusted edgewise fixed appliances

(MBT prescriptions, 0.022” x 0.028” slot size) on buccal and labial

surfaces during the previous 3 months, and had gingivitis on

at least half the number of total teeth erupted. Exclusion criteria

were subjects with impairment in hearing and vision, illiterate and

patients with craniofacial syndromes.

Information leaflet and consent

Information leaflet was prepared and patient was given time to

read the study design. Written consent form was given and signed

by the subjects. For subjects below 18 years old, parental consent

was recorded.

Oral hygiene instruction (OHI)

Group 1: A 5-minute OHI was given verbally by referring to a

written script. This verbal OHI was aided by the use of a model,

a toothbrush and an interdental brush.

Group 2: A 5-minute verbal instruction supplemented with a patient

information leaflet specially designed for this study was delivered.

The leaflet had similar information with Group 1.

Group 3: Participants were instructed to watch a specially designed

5-minute long video at chairside with the same amount

of information as in Group 1 and 2, but was presented in audiovisual

format.

Each session was restricted to five minutes and subjects were given

additional two minutes at the end of the session should there

be any questions.

Each OHI was introduced with five sections. First, subjects were

advised to use soft bristle toothbrush and fluoridated toothpaste.

The second section was to emphasize on the duration of tooth

brushing which was two minutes per session for twice a day. Next

was to teach comprehensive brushing technique by using modified

Bass technique to ensure no surfaces were left out. The participants

were instructed to focus on cleaning on the gingival third

and the area surrounding the brackets. The fourth section was on

interdental brushing using interdental brushes to clean the area

surrounding the orthodontic brackets for at least once per day.

The last section was on dietary advice which focused on reducing

the sugar amount and acidic food or beverage intake.

Calibration

Inter-examiner calibration was done to achieve synchronized

agreement between the two clinicians (N.M. and R.H.) in terms

of periodontal parameters measurements. Calibration was also

done to standardize the OHI delivery of all three methods.

Clinical procedure

At the start of the study and before the instructional methods

were given, each subject was examined for plaque index (PI),

gingival index (GI) and bleeding on probing (BOP) on six index

teeth: all second premolars (5’s), upper right central incisor (11)

and lower left central incisor (31). In the absence of 5’s, first premolars

(4’s) were used. Patients were seen six weeks later and the

periodontal parameters (PI, GI and BOP) were repeated for the

six index teeth.

Plaque index (PI)

The index tooth was divided into eight boxes by putting imaginary

lines dividing three parts of the tooth vertically and horizontally

with the bracket in the centre (Figure 1).

Plaque disclosing dye (Rondell Disclosing Pellets, Directa Dental

Company, Sweden) was applied on buccal and labial surfaces of

the six index teeth. Subjects were then asked to rinse their mouth

and the clinicians recorded the presence of plaque by placing a

tick into the respective boxes in a data collection form. Plaque was

scored corresponding to the eight boxes.

The maximum score for each patient was 48 ticks (8 ticks X 6

teeth). Score was calculated by adding the number of ticks on the

index teeth and divided by 48. The score was then multiplied by 100 to get the number in percentage.

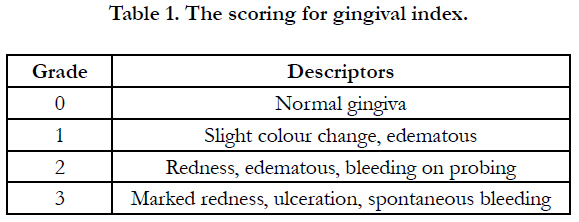

Gingival index (GI)

Gingival index was based on Loe and Silness (1963)[9] with a

scoring of 0 to 3. The grading used for gingival index was described

in Table 1.

William’s periodontal probe (Periodontal Probe 546/1, Medesy

Srl, Italy) was used with gentle pressure on the same index teeth

evaluated for plaque index. The tooth was examined on the buccal

and labial surfaces and it was divided into three sites (mesial,

mid and distal).

The maximum score for a site was 3 thus the maximum score for

a tooth was 9. The maximum sum for all the teeth was 54 (score 9

x 6 teeth). Therefore, gingival index was calculated by adding the

score for all sites and divided by 54. The score was then multiplied

by 100 to get the number in percentage.

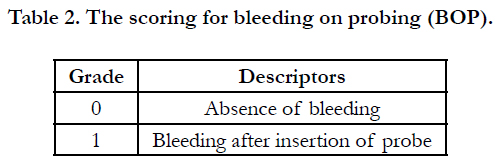

Bleeding on probing (BOP)

Bleeding on probing was also examined on buccal and labial surfaces

of the six index teeth and it was again divided into 3 sites

(mesial, mid and distal). William’s periodontal probe (Periodontal

Probe 546/1, Medesy Srl, Italy) was used with gentle pressure to

evaluate the BOP.Presence of bleeding was checked after a minimum

of ten seconds. The score was given based on the criteria

described in Table 2.

Maximum score for one site was 1, hence the maximum score

for 1 tooth was 3. The maximum scoring for all six teeth was 18

(score 3 x 6 teeth). Thus, BOP was calculated by summation of

the score for all sites and divided by 18. Percentage was then calculated

after multiplying the score by 100.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistic was used to summarize the demographic

backgrounds of the subjects. As the data was normally distributed,

parametric tests were used to analyse the result. Paired sample

t-test was used in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

software (SPSS version 20.0, IBM Corporation, United States of

America) to measure if there was any statistically significant difference

between pre and post-OHI in each group. Next, one-way

analysis of variance (ANOVA) was ran to compare if there was

any statistically significant difference between the verbal, verbalwritten

and video methods. P-value was set at less than 0.05 to

indicate statistical significance.

Results

39 subjects consisting of 31 females (79.5%) and 8 males (20.5%)

were analysed. The mean age of the participants was 16.9 ± 2.3

and ranged from 13 to 22 years old.

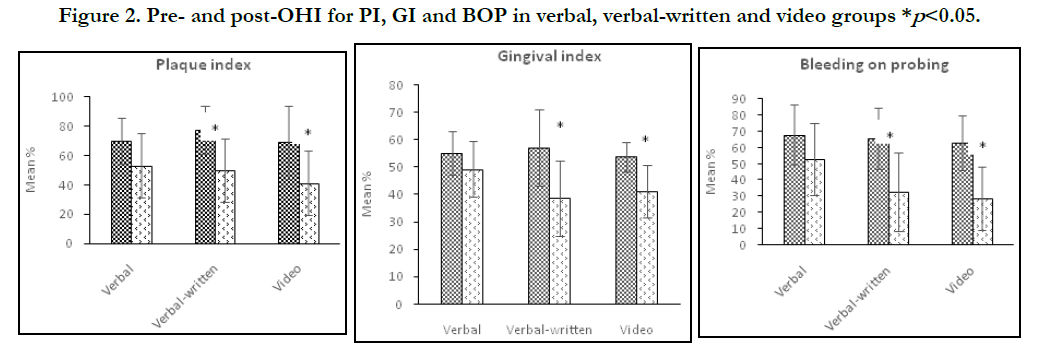

Reduction of PI, GI and BOP in each group

There was a reduction in the mean percentage of PI, GI and BOP

in all three groups. The t-test revealed that the reduction in verbal

group was statistically significant only for plaque index (p=0.012).

Gingival index (p=0.085) and bleeding on probing (p=0.062) did

not have statistical significant reduction in the verbal group. For

verbal-written and video groups, the changes in the mean percentage

were much larger and the reduction of all periodontal parameters

were statistically significant (Figure 2).

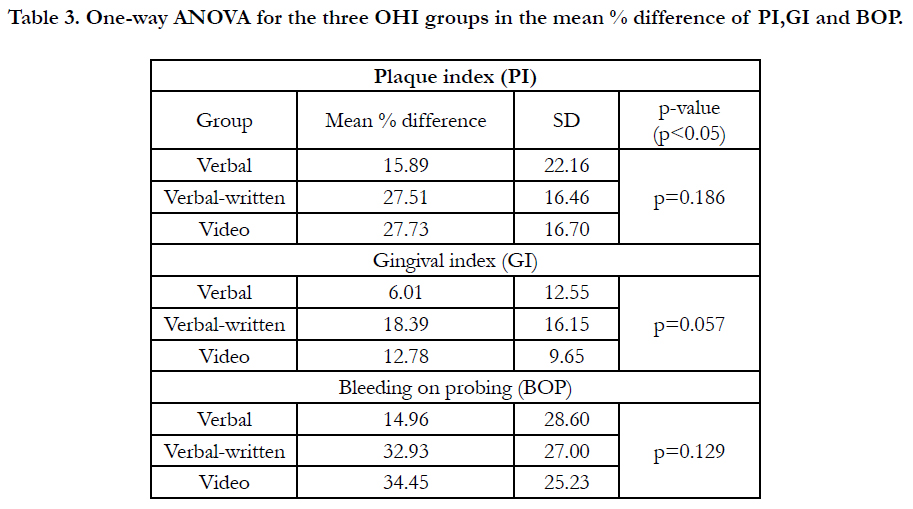

Comparisons of PI, GI and BOP between groups

One-way ANOVA revealed no statistically significant difference

between the three groups, although the improvement in GI had

p=0.057, a value that was very close to significance (Table 3).

Discussion

Patients wearing fixed appliances are highly associated with the

deterioration of gingival health due to the increase in plaque retentive

factor which enhances the accumulation of harmful microorganisms.[

3, 10] In accordance with that, proper OHI to patients

is very crucial to avoid the worsening of periodontal health

and therefore the best technique of OHI must be properly studied

to improve periodontal health.

The OHI given in this study emphasized on brushing with modified

Bass technique, using soft bristle toothbrushes and fluoridated

toothpaste for two minutes as they were proved to improve

oral hygiene and gingival health of orthodontic patients.[11] Interdental

brushing and reduction in dietary sugar intake were also

recommended to maximise the beneficial effects on periodontal

health. Interdental cleaning improves the effectiveness of eliminating

plaque interdentally which contributes to inflammation of

gingiva,[12] and controlled sugar may reduce the formation of the

plaque itself.[13]

Three periodontal parameters used in this study were PI, GI and

BOP. All three parameters were non-invasive, and were indicators

of different aspects of periodontal health. Plaque index was

analysed because dental plaque is the main predisposing factor

for gingivitis and periodontitis.[14] Meanwhile, gingival index assessed

the degree of inflammation at the marginal gingiva area

and bleeding on probing was used to indicate the gingival condition

at the base of the sulcus.[15]

Subjects in the verbal-written group exhibited significant improvements

in their periodontal parameters (PI, GI, BOP). Our

finding is parallel with the findings from Johnson and Sandford

[16] and Zuhal et al [17] who found that health instructions given

both verbally and written were more effective than verbal only.

In our study, standardization was a crucial key in the effectiveness

of the OHI as the information can be disseminated evenly

supplemented with written materials. Our research contrasts with

that of Lees and Rock [6] who argued that written information

resulted in the least improvement in the gingival health of patients

wearing fixed appliances when compared to verbal and

video techniques. The difference could be explained by the fact

that their subjects brought the illustrated instructions home without

any verbal component. It is also unclear whether the patients

actually took the initiative to read the written materials provided.

Therefore, it would appear that verbal OHI when given with written

materials could increase the effectiveness of information delivery

when compared with verbal or written instructions alone.

Shah et al [18] and Moshkelgosha et al [8] pointed out that subjects receiving video OHI had significant improvement in their gingival

health, similar to that found in our study. A likely explanation

is that standardization of information could be implemented via

audio-visual format and that the instructions could be replayed

as many times as required.[18] Although participants who were

illiterate were excluded, video OHI might be better appreciated by

this group of patients in real world due to its dynamic, interesting

and lively characteristics. It was interesting to highlight that in

our clinical observations, patients who received video-type OHI

were more engaged in the advices given, most probably stems

from the animation and illustration as well as the usage of various

colours which attracted their attention. Thus, verbal instructions

supplemented by visuals or written instructions helped improve

the gingival health of fixed appliance patients in our study.

On another side, our result contradicted with Lees and Rock [6]

who found that verbal OHI method resulted in the most improvement

in periodontal health. Their instructions given to the subjects

were not standardized especially in the duration, which lasted

up to thirty minutes in some subjects. The long OHI duration was

not employed in our study due to the possibility of low attention

span in adolescent group. The different method in obtaining the

plaque index in which they excluded the incisal/occlusal third of

the index tooth may also affect the result. Although they believed

that fixed appliance components only affected cleansing at the

gingival two-thirds, our opinion and findings differ as the incisal

part of the bracket was also a plaque retentive site. The presence

of plaque at the incisal third was particularly common. Subjects

were also more likely to lose interest during verbal OHI due to the

lack of visual aids, and verbal-only information did not help with

information retention among adolescents.[19] It was also noteworthy

to point that only plaque index showed improvement for

verbal group. From our perspective, due to the lack of attention

given by the patients during verbal OHI, they might be less proactive

in practicing the advices given. Since changes in the state

of gingival inflammation (reflected by GI and BOP) need longer

duration to manifest,[20] only plaque index showed significant

improvement in our study.

Our study did not find any significant differences between the

effectiveness of the three groups. This may be caused by other

factors apart from the techniques of delivering the advices. From

the ten social determinants of health outlined by World Health

Organization (WHO), the factors which are relevant to oral health

are dietary style and social gradient,[21] which might play a role in

the patients’ oral health condition, despite the success of various

OHI techniques delivered.

Excessive sugar intake is harmful for oral health as it may contribute

to the formation of dental plaque and cause oral diseases.

[13] Although advices on dietary sugar intake was included in

our OHI, its relation to the gingival health was not assessed. For

instance, verbal group might have more subjects who have high

sugar intake than the video group and as a result, the improvement

of oral hygiene of patients receiving verbal OHI might be

less remarkable than the video OHI group.

Next, people who are lower down the social hierarchy are two

times more likely to have serious diseases due to unfavourable

social surrounding and economical factor.[21] This is significant

since subjects with lower socioeconomical status tend to have

higher sugar intake and have less exposure to effective oral hygiene.[

22] Therefore, participants having different lifestyle might

not have the same level of motivation in improving their oral hygiene

practices albeit similar information delivered during OHI.

Changes in patients’ oral health is very dependent on the level

of knowledge and attitude exhibited by the individuals. This can

be understood through the ‘knowledge, attitude, practice’ (KAP)

theory by Pine and Harris.[23] A health education must follow the

KAP route to ensure success in patient’s attitude and behavioural

change. This model implies that practice is a patient’s response

to the information given, and therefore factors affecting the level

of knowledge and attitude of the person affect significantly their

level of application. The knowledge component was given in our

study by delivering the OHI through the three different methods.

However, the ability of the participants to truly understand and

practise the advices given were not objectively assessed.

The findings of this study might be helpful in facilitating the clinicians

and dental hygienist when emphasizing on the importance

of proper plaque control in patients wearing fixed appliance. Although

it did not indicate one specific OHI method is better than

the other, the results revealed that oral hygiene instructions still

play a very important role in maintaining good gingival health

throughout the fixed appliance treatment regardless of the methods

of delivery. The visual aids and leaflets used in the study have

the potential to be used as powerful educational tools during OHI

and orthodontic consent process.

Studies with longer duration of follow-up could be done because

the rate of gingival health improvement may vary from patients to

patients, and their long-term compliance to the instructions could

be assessed. In addition, studies to focus onpatient’s challenges in

practising the oral health instructions could be done.

In conclusions, whilst verbal method is effective in improving the

plaque index, verbal-written and video methods were effective in

improving all aspects of gingival health (plaque index, gingival

index and bleeding on probing) in patients wearing fixed appliances.

There is no single best method in delivering oral hygiene

instructions to patients with fixed appliances.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research was funded by IIUM Research Acculturation Grant

Scheme (IRAGS) 2018 from International Islamic University Malaysia

(IRAGS18-045-0046).

References

-

[1]. Al-Mobeeriek A, AlDosari AM. Prevalence of oral lesions among Saudi dental

patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2009 Sep-Oct;29(5):365-8. PubMed PMID:

19700894.

[2]. dos Santos Júnior J. Occlusion: Principles and Treatment. Quintessence Publishing (IL); 2007.

[3]. Firestone AR, Scheurer PA, Bürgin WB. Patients' anticipation of pain and pain-related side effects, and their perception of pain as a result of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur J Orthod. 1999 Aug;21(4):387-96. PubMed PMID: 10502901.

[4]. Majorana A, Bardellini E, Flocchini P, Amadori F, Conti G, Campus G. Oral mucosal lesions in children from 0 to 12 years old: ten years' experience. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral RadiolEndod. 2010 Jul;110(1):e13-8. PubMed PMID: 20452255.

[5]. Köse O, Güven G, Özmen I, Akgün ÖM, Altun C. The oral mucosal lesions in pre-school and school age Turkish children. J EurAcadDermatolVenereol. 2013 Jan;27(1):e136-7. PubMed PMID: 22188486.

[6]. Kramer IR, Pindborg JJ, Bezroukov V, Infirri JS. Guide to epidemiology and diagnosis of oral mucosal diseases and conditions. World Health Organization. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1980 Feb;8(1):1-26. Pub- Med PMID: 6929240.

[7]. Barmes DE, Infirri JS. WHO activities in oral epidemiology. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1977 Jan;5(1):22-9. PubMed PMID: 264415.

[8]. Hussein SA, University of Sulaimani, Noori AJ. Prevalence of oral mucosal changes among 6- 13 year old children in Sulaimani city, Iraq. Sulaimani Dent J. 2014;1:5-9.

[9]. Bessa CF, Santos PJ, Aguiar MC, do Carmo MA. Prevalence of oral mucosal alterations in children from 0 to 12 years old. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004 Jan;33(1):17-22. PubMed PMID: 14675136.

[10]. Govindaraju L, Gurunathan D. Effectiveness of Chewable Tooth Brush in Children-A Prospective Clinical Study. J ClinDiagn Res. 2017 Mar;11(3):ZC31-ZC34. PubMed PMID: 28511505.

[11]. Christabel A, Anantanarayanan P, Subash P, Soh CL, Ramanathan M, Muthusekhar MR, et al. Comparison of pterygomaxillarydysjunction with tuberosity separation in isolated Le Fort I osteotomies: a prospective, multicentre, triple-blind, randomized controlled trial. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016 Feb;45(2):180-5. PubMed PMID: 26338075.

[12]. Soh CL, Narayanan V. Quality of life assessment in patients with dentofacial deformity undergoing orthognathic surgery--a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013 Aug;42(8):974-80. PubMed PMID: 23702370. [13]. Mehta M, Deeksha, Tewari D, Gupta G, Awasthi R, Singh H, et al. Oligonucleotide therapy: An emerging focus area for drug delivery in chronic inflammatory respiratory diseases. ChemBiol Interact. 2019 Aug 1;308:206- 215. PubMed PMID: 31136735.

[14]. Ezhilarasan D, Apoorva VS, Ashok Vardhan N. Syzygiumcumini extract induced reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis in human oral squamous carcinoma cells. J Oral Pathol Med. 2019 Feb;48(2):115-121. PubMed PMID: 30451321.

[15]. Campeau PM, Kasperaviciute D, Lu JT, Burrage LC, Kim C, Hori M, et al. The genetic basis of DOORS syndrome: an exome-sequencing study. Lancet Neurol. 2014 Jan;13(1):44-58. PubMed PMID: 24291220.

[16]. Kumar S, Sneha S. Knowledge and awareness regarding antibiotic prophylaxis for infective endocarditis among undergraduate dental students. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2016 Oct 1:154-9.

[17]. Christabel SL, Gurunathan D. Prevalence of type of frenal attachment and morphology of frenum in children, Chennai, Tamil Nadu. World J Dent. 2015 Oct;6(4):203-7.

[18]. Kumar S, Rahman R. Knowledge, awareness, and practices regarding biomedical waste management among undergraduate dental students. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017 Aug 1;10:341-5.

[19]. Sridharan G, Ramani P, Patankar S. Serum metabolomics in oral leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2017 Jul- Sep;13(3):556-561. PubMed PMID: 28862226.

[20]. Ramesh A, Varghese SS, Doraiswamy JN, Malaiappan S. Herbs as an antioxidant arsenal for periodontal diseases. J IntercultEthnopharmacol. 2016 Jan 27;5(1):92-6. PubMed PMID: 27069730.

[21]. Thamaraiselvan M, Elavarasu S, Thangakumaran S, Gadagi JS, Arthie T. Comparative clinical evaluation of coronally advanced flap with or without platelet rich fibrin membrane in the treatment of isolated gingival recession. J Indian SocPeriodontol. 2015 Jan-Feb;19(1):66-71. PubMed PMID: 25810596.

[22]. Thangaraj SV, Shyamsundar V, Krishnamurthy A, Ramani P, Ganesan K, Muthuswami M, et al. Molecular Portrait of Oral Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma Shown by Integrative Meta-Analysis of Expression Profiles with Validations. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 9;11(6):e0156582. PubMed PMID: 27280700.

[23]. Ponnulakshmi R, Shyamaladevi B, Vijayalakshmi P, Selvaraj J. In silico and in vivo analysis to identify the antidiabetic activity of beta sitosterol in adipose tissue of high fat diet and sucrose induced type-2 diabetic experimental rats. ToxicolMech Methods. 2019 May;29(4):276-290. PubMed PMID: 30461321.

[24]. Ramakrishnan M, Bhurki M. Fluoride, fluoridated toothpaste efficacy and its safety in children-review. Int J Pharm Res. 2018 Oct 1;10(04):109-4.

[25]. Shulman JD. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in children and youths in the USA. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005 Mar;15(2):89-97. PubMed PMID: 15790365.

[26]. Baricevic M, Mravak-Stipetic M, Majstorovic M, Baranovic M, Baricevic D, Loncar B. Oral mucosal lesions during orthodontic treatment. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2011 Mar;21(2):96-102. PubMed PMID: 21121986.

[27]. Favia G, Limongelli L, Tempesta A, Maiorano E, Capodiferro S. Oral lesions as first clinical manifestations of Crohn's disease in paediatric patients: a report on 8 cases. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2020 Mar;21(1):66-69. PubMed PMID: 32183532.

[28]. Hong CHL, Dean DR, Hull K, Hu SJ, Sim YF, Nadeau C, et al. World Workshop on Oral Medicine VII: Relative frequency of oral mucosal lesions in children, a scoping review. Oral Dis. 2019 Jun;25Suppl 1:193-203. PubMed PMID: 31034120.

[29]. Oral Mucosal Space/Surface Lesions. Diagnostic Imaging: Oral and Maxillofacial. 2017:926–9.

[30]. Reichart PA. Oral mucosal lesions in a representative cross-sectional study of aging Germans. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000 Oct;28(5):390-8. PubMed PMID: 11014516.

[31]. Ali M, Sundaram D. Biopsied oral soft tissue lesions in Kuwait: a sixyear retrospective analysis. Med PrincPract. 2012;21(6):569-75. PubMed PMID: 22699793.

[32]. de Muñiz BR, Crivelli MR, Paroni HC. Clinical study of oral soft tissue lesions in boys in a children's home. Rev AsocOdontol Argent. 1981 Sep- Oct;69(7):405-8. PubMed PMID: 6950468.

[33]. Medina AC, Sogbe R, Gómez-Rey AM, Mata M. Factitial oral lesions in an autistic paediatric patient. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003 Mar;13(2):130-7. PubMed PMID: 12605633.

[34]. Kovac-Kovacic M, Skaleric U. The prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in a population in Ljubljana, Slovenia. J Oral Pathol Med. 2000 Aug;29(7):331- 5. PubMed PMID: 10947249.

[35]. Jin X, Zeng X, Wu L. Oral Mucosal Lesions of Systemic Diseases. Case Based Oral Mucosal Diseases. 2018:169-97.

[36]. VijayashreePriyadharsini J. In silico validation of the non-antibiotic drugs acetaminophen and ibuprofen as antibacterial agents against red complex pathogens. J Periodontol. 2019 Dec;90(12):1441-1448. PubMed PMID: 31257588.

[37]. J PC, Marimuthu T, C K, Devadoss P, Kumar SM. Prevalence and measurement of anterior loop of the mandibular canal using CBCT: A cross sectional study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2018 Aug;20(4):531-534. PubMed PMID: 29624863.

[38]. Ramesh A, Varghese S, Jayakumar ND, Malaiappan S. Comparative estimation of sulfiredoxin levels between chronic periodontitis and healthy patients - A case-control study. J Periodontol. 2018 Oct;89(10):1241-1248. PubMed PMID: 30044495.

[39]. Ramadurai N, Gurunathan D, Samuel AV, Subramanian E, Rodrigues SJL. Effectiveness of 2% Articaine as an anesthetic agent in children: randomized controlled trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2019 Sep;23(9):3543-3550. PubMed PMID: 30552590.

[40]. Sridharan G, Ramani P, Patankar S, Vijayaraghavan R. Evaluation of salivary metabolomics in oral leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2019 Apr;48(4):299-306. PubMed PMID: 30714209.

[41]. Ezhilarasan D, Apoorva VS, Ashok Vardhan N. Syzygiumcumini extract induced reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis in human oral squamous carcinoma cells. J Oral Pathol Med. 2019 Feb;48(2):115-121. PubMed PMID: 30451321.

[42]. Mathew MG, Samuel SR, Soni AJ, Roopa KB. Evaluation of adhesion of Streptococcus mutans, plaque accumulation on zirconia and stainless steel crowns, and surrounding gingival inflammation in primary molars: randomized controlled trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2020 Sep;24(9):3275-3280. PubMed PMID: 31955271.

[43]. Samuel SR. Can 5-year-olds sensibly self-report the impact of developmental enamel defects on their quality of life? Int J Paediatr Dent. 2021 Mar;31(2):285-286. PubMed PMID: 32416620.

[44]. R H, Ramani P, Ramanathan A, R JM, S G, Ramasubramanian A, et al. CYP2 C9 polymorphism among patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma and its role in altering the metabolism of benzo[a]pyrene. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2020 Sep;130(3):306-312. PubMed PMID: 32773350.

[45]. Chandrasekar R, Chandrasekhar S, Sundari KKS, Ravi P. Development and validation of a formula for objective assessment of cervical vertebral bone age. ProgOrthod. 2020 Oct 12;21(1):38. PubMed PMID: 33043408.

[46]. VijayashreePriyadharsini J, SmilineGirija AS, Paramasivam A. In silico analysis of virulence genes in an emerging dental pathogen A. baumannii and related species. Arch Oral Biol. 2018 Oct;94:93-98. PubMed PMID: 30015217.