The Role of CD44 Cancer Stem Cell Marker in the Development and Progression of Lymph Node Metastasis in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Ahmed M. Hussein1, Asmaa M Zahran2, Mohamed Badawy3, Hany G. Gobran4, Mohamed F. Edrees5, Enas M. Omar6*

1 Lecturer of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Department, Faculty of Dentistry, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt.

2 Associate Professor Clinical Pathology Department, South Egypt Cancer Institute, Assiut University, Egypt.

3 Lecturer of Oral Biology Department, Faculty of Dentistry, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt.

4 Associate of Oral BiologyDepartment, Faculty of Dentistry, Al-Azhar University (Boys Branch), Egypt.

5 Assistant Lecturer Oral Medicine and Periodontology Department, Faculty of Dentistry, Al-Azhar University, Assiut, Egypt.

6 Lecturer of Oral PathologyDepartment, Faculty of Dentistry, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt.

*Corresponding Author

Enas M. Omar,

Lecturer of Oral PathologyDepartment, Faculty of Dentistry, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt.

Tel: +201225155647

E-mail: inas.magdy@alexu.edu.eg/Inas.magdy@gmail.com

Received: October 05, 2021; Accepted: November 05, 2021; Published: November 09, 2021

Citation: Ahmed M. Hussein, Asmaa M Zahran, Mohamed Badawy, Hany G. Gobran, Mohamed F. Edrees, Enas M. Omar. The Role of CD44 Cancer Stem Cell Marker in the

Development and Progression of Lymph Node Metastasis in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int J Dentistry Oral Sci. 2021;8(10):4917-4922. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2377-8075-21000994

Copyright: Enas M. Omar©2021. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Introduction: Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC)management is challengingdue to high tendency of local invasion and

metastasis.Cancer stem cells hold highsignificanceas theyhaveself-renewal ability, which further allowscancer progression and

metastasis.Hence, it is crucial to evaluate different specialised markers for stem cells,such as CD44,to detect their role in tumour

metastasis.Flow cytometry (FCM) offers a quick and automated assessment of ploidy status andcell proliferation of the

neoplasm by resolvingthe nuclear DNA contents.

Aim of the study: The objective of thispaperis to evaluate theCD44 expression and analyseDNA content by FCM to predict

the expansion of lymph node metastasis in patients with OSCC.

Material and Methods: 50paraffin-embedded tissues of metastatic and non-metastatic lymph node OSCCwereimmunostainedby

CD44for assessing cancer stem cell activity in each lesion. Furthermore, each selected tissue underwent flow

cytometric analysis to demonstratethe DNA activity between the tested groups.

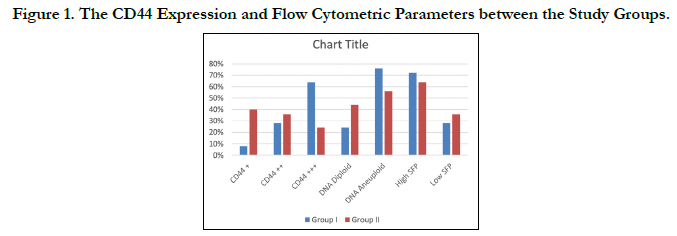

Results: The CD44 expression in OSCCsshowed a marked difference between the metastatic and non-metastatic lymph node

cases. Furthermore, flow cytometric analysis of the DNA parameters between the tested groups revealed a powerful difference

of DNA ploidy. The S-phase fraction(SPF) between the groups showed no compelling result.All specimens had a higher

CD44 expression, aneuploid DNA content and high SPF, whichdemonstrateddepositsof cervical metastatic lymph nodes.

Conclusions: The CD44 and the flow cytometric analysis of the DNA ploidy correlationoffer a significantprediction to

determine the OSCCcompetence .

2.Introduction

3.Materials and Methods

3.Results

4.Discussion

5.Conclusion

5.References

Keywords

CD44; Cancer Stem Cell; Flow Cytometry; DNA Ploidy; S-Phase Fraction..

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is, particularly, the mostfamiliaroral

head and neck cancer worldwide. It always demonstratea

poor prognosis becauseof its late-stage diagnosis, local

invasion and the recurrence of primary carcinomas. A study has

revealed that the presence of lymph node metastasis is considered

as the eventual and pivotal prognostic signal of survival and recurrence.[

1] The assessment of lymph node status plays a crucial

role in the treatment plan and the prediction of the patient survival.

However,a part ofhidden lymphatic metastases is still missed

in investigation, which contribute in reducing the survival rate.[2,

3] However, in early-stage OSCC, the adoption of elective neck

dissection has been questionable during the previous several decades.

The regional lymph node metastasis through the pathologic

evaluation is recognised in only a few patients. For those patients

without lymph metastasis, the undesirable cosmetic and functional

effects along with an increasing morbidity of neck dissection

should be avoided. Thus, it is essential to meticulously predict

lymph node metastasis before the surgery [4]. This phenomenon

indicates the need for establishing other methods to determine

the propensity for metastasis.

One of the theses regarding oral carcinogenesis and metastasis

state that the neoplasm growth depends on cancer stem cells with

self-renewal abilities that can advocate cancer initiation, advancementand

metastasis.[5] Explicit markers for these cells such as

CD44 were investigated to promote a profound understanding

for CSCs’actions in carcinogenesis and metastasis.[6] The CD44

is a cell surface glycoprotein assuming as a dominant receptor

for hyaluronic acid. It participates in physiologic and pathologic

processes such as lymphocyte homing, wound healing, angiogenesis

and malignant diseases. It is also associated in cell attachment

and migration.[6] The CD44 antigen is marked by the CD44 gene

loaded on chromosome 11. Additionally, the CD44 is believed to

be involved in cancer progression and metastasis as a regulator of

growth, survival, differentiation, and migration.[7, 8]

A great deal of interest has been directed towards using flow cytometric

DNA analysis as an objective tool to study the natural

history of SCC of the head and neck. Tumour DNA content is

asserted to be one of the prognostic and metastatic indicators in

this cancer.Several investigators have studied the same with respect

to lymph node metastasis.[9-11] DNA ploidy has proven

to be a useful prognostic indicator in various neoplasms.[12] The

analysis of solid lesions by flow cytometry (FCM) permits rapid,

objective, quantitative evolution and proliferative activity of cellular

DNA content.[13] Neoplasms are usually classified according

to their ploidy status into diploid typeswith a normal amount

of DNA (2N) and aneuploid ones with an abnormal amount of

DNA. Besides, the FCM also provides some assessment of cellular

proliferative activity, defined by S-phase fraction (SPF), all

of which may add a new dimension to the present pathologic and

metastatic potentials of malignancy [14]. Computer-assisted cell

cycle analysis by FCM provides the sensitivity for exposure near

diploid/aneuploid peaks. FCM also possessesthe advantage of allowing

retrospective studies of paraffin-embedded tissue samples

as well as from fresh or frozen tissue samples.[15] However, there

are few reports on the relationship of flow cytometric analysis

of nuclear DNA content of oral carcinomas with regional lymph

node metastasis.

The objective of this research is to study the CD44 expression

of CSCs and conduct flow cytometric analysis of nuclear DNA

content of OSCC. This research further evaluates the diagnostic

significance of these methods in anticipating the possibility of

cervical lymph node metastasis.

Materials and Methods

This research was reviewed and approved by the institute’s ethical;

board (IORG#:IORG0008839). The cases were retrospectively

retrieved between 2015-2020 and obtained from incisional or excisional

primary tumor biopsies during the same period of time

from files of Oral Pathology Department, Faculty of Dentistry,

Alexandria University over the last five years. Clinical data, including

age, sex, site were obtained from the original pathology

reports. Patients with OSCC who had at least one pathologically

metastatic node were evaluated in a ratio of 50:50 (Group I). The

remaining lesions with no data of any regionally mph node metastasis

were categorised into Group II. Clinical staging, pathological

differentiation and mode of infiltration of the primary carcinomas

were defined based on the Union for International Cancer

Control TNM Classification of Malignant Neoplasms and the

World Health Organization’s classification.[16, 17]

In this study’s tissue samples, one section having a thickness of

5 µmwas cut from each block and stained with haematoxylin and

eosin for the verification of diagnosis. Importantly, histopathological

grading reassures that the neoplasm tissue constitutes

more than 70% of the section, with minimal haemorrhagic andnecrotic

foci. This step is essentialin obtaining accurate results

and avoiding errors produced by analysing normal, inflammatory

or necrotic tissues.

The tissue paraffin blocks were stained by an anti–CD44 antibody

immunohistochemistry marker (Abcam, Cambridge, UK)

to compare its different expressions among metastatic and nonmetastatic

lymph node OSCC. The staining steps were conducted

while adhering to the universal immunostaining protocols. The

strength of the CD44 immunoreaction was evaluated in terms of

both means area (%)and optical density by using the image analyser

(Faculty of Oral and Dental Medicine, South Valley University).

Each specimen was marked according to the power of the

nuclear and cytoplasmic staining: no staining, 0; weak staining, +;

moderatestaining, ++; and strong staining, +++.

From each block, 3 pieces having a thickness of 50 µmwere cut

and transmitted to the FCM Unit, Clinical Pathology Department,

South Egypt Cancer Institute, Assiut University for flow cytometric

analysis using Becton–Dickinson (B–D) FACS Calibur flow

cytometer (USA). Specimens were stained by thecycle test TMplus

DNA Reagent Kit (BD Biosciences. For each selected block,

thickness of 50 µm were placed into a labelled glass culture tube

with dimensions of 16 × 125 mm. Nuclear suspensions of solid

lesions were prepared using a modified version method18 The

samples with a single G0/G1 peak were classified as DNA diploid.

If two discrete G0/G1 peaks were present with an abnormal

G0/G1 peak containing a minimum of 15% of the total events

and having a corresponding G2/M peak, then the neoplasms

were considered as DNA aneuploidy.[19] The DNA index (DI)

was recorded by the calculation programme for the DNA analysis

system. The SPF is the fraction of the full cell residents that are

present in the S-phase of the cell cycle and is usually asserted as

a ratio. The cut-off for the SPF was set as the mean ±2 standard

deviation (SD) and considered as either being low or high.

The data were collected, tabulated and statistically analysed using

the SPSS system (release 11.0 software). All results were expressed

as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was employed to test

the data between the examined neoplasms. It was also used to

analyse the mean CD44 area (%) and the optical density of immunohistochemical

results. The FCM variables between the research

groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test

and Kruskal–Wallis test. Chi-squared (±2) test was performed tocomparethe

categorical data. P< 0.05 was considered significant

in all the statistical results..

Results

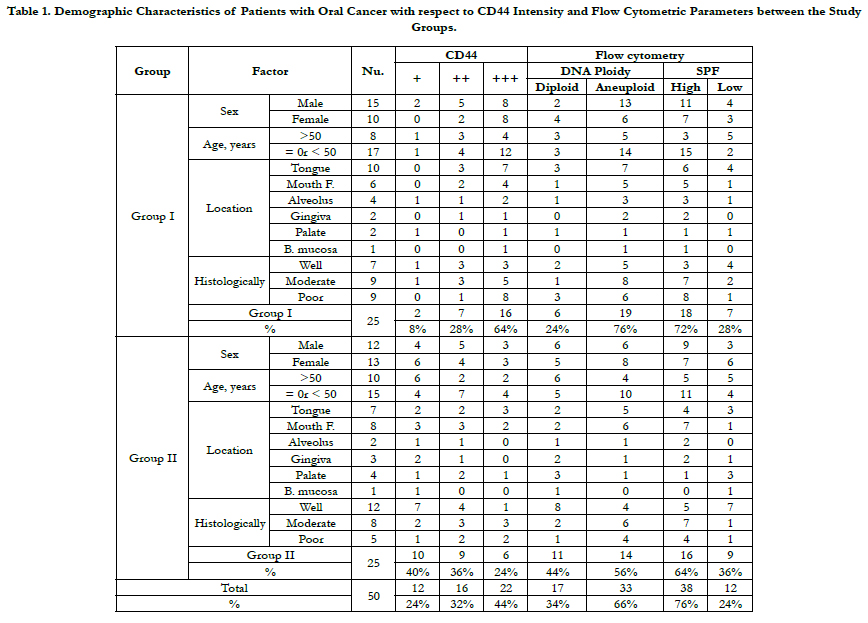

Thisstudy was performed on 50 OSCC specimens at different

clinical stages with variable histological grades. Half of the specimens

with positive lymph node metastasis were identified (Figure

1). The increase in CD44 expression and aneuploidy state was powerfully associated with a higher stage and grade of disease,

where as no relationship observed between CD44 immunoreactivity

or aneuploidy state and patients’ gender, age and neoplasm

location (Table 1).

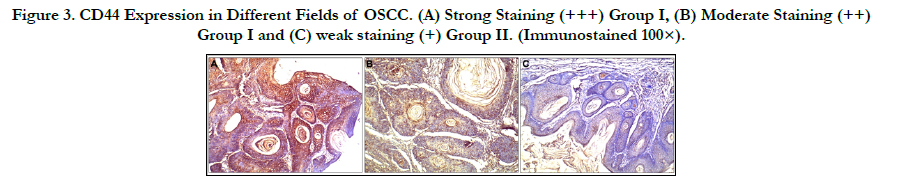

The immunoreaction to CD44 in the different tested groups

showed variations in both mean area (%) and the optical density

(Figure 2).In Group I, the mean CD44 area was 66.14 ± 7.54%,

and the mean CD44 optical density was 74.46 ± 11.58. A total

of16 specimens (64%) exhibited strong staining (+++); 7 tumours

(28%) exhibited moderate staining (++) and only 2 lesions

(8%) exhibited weak staining (+). In Group II, the mean CD44

area was 44.06 ± 7.43%, and the mean CD44 optical density was

54.35 ± 9.52. A total of 10 neoplasms (40%) showed weak staining

(+);9 tumours (36%) showed moderate staining (++) and 6

lesions (24%) expressed strong staining (+++).The differences in

both mean CD44 area (%)and optical density were highly statistically

significant (p <0.0001), as shownin the comparison between

Group I and Group II. As expected, the expression of CD44

was lower in non-metastatic cases (Group II) as compared to the

metastatic lesions (Group I). Despite this result, it was noted that

a decreased level of CD44 should not be considered exclusively

for the possibility of lymph node metastasis.

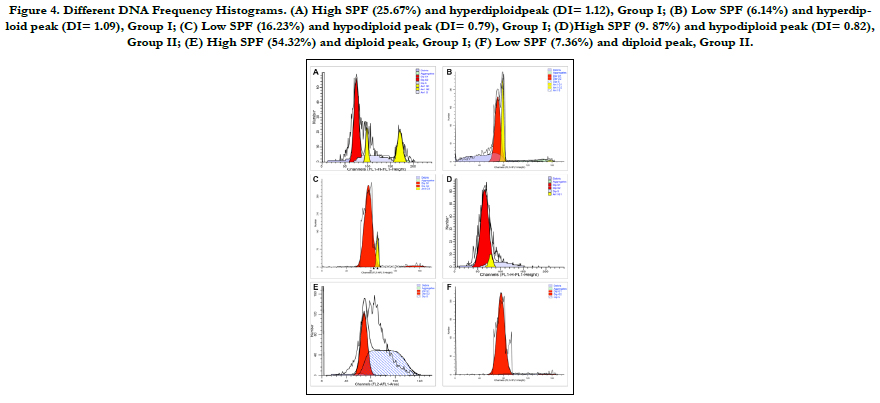

In the flow cytometric analysis (Figure 3), 33 (66%) lesions were

found to have aneuploid cell populations and the remaining 17

tumours had a diploid cell population. Aneuploidy was observed

in 19 out of 25 (76%) specimens in Group I and in 14 out of 25

(56%) tumours in Group II. The aneuploid neoplasms further

were divided into: hyperdiploid with DI ranging from 1.05 to 1.82

with a mean of 1.45 (13 in Group I and 7 in Group II) and hypodiploid

with DI ranging from 0.71 to 0.97 with a mean of 0.85

(6 in Group I and7 in Group II). The difference in diploid and

aneuploid DNA patterns (the ploidy state) between Group I and

Group II was statistically significant (p= 0.002). There is no symbolic

difference in the numbers of hyperdiploid and hypodiploidcases

between Group I and Group II (p= 0.657). The SPF values

calculated for Group I ranged between 6.14% and 67.21% with a

mean of 24.77%,whereas the SPF values calculated for Group II

ranged between 4.49% and 43.19% with a mean of 15.35%. The

S-phase values were furthered classified into high and low. About

72% (18 out of 25) of specimens in Group I had high SPF value

(numbers of cells in SPF were equal or more than 24.77%), and

28% (7 out of 25) of tumours had low SPF value. In Group II lesions,

nearly 64% (16/25) of cases had high SPF (number of cells

in SPF were more than 15.35%), and 9 lesions(36%) had low SPF

values. There is noimportant difference in the mean SPF value of

Group I and Group II specimens (p= 0.537).

There is a high significance difference (p <0.0001) between the

specimens with strong CD44 expression, aneuploid content and

high SPF (64%, in 16 out of 25) in Group I and the same examined

lesions (24%, in 6 out of 25) in Group II. This research result

determined that the CD44 expression collaborates with the FCM

analysis results of the tumour DNA content. Furthermore, this

result establishes that CD44 expression is astrong diagnostic indicator

for anticipating the qualification of oral cancer to produce

cervical lymph node metastasis.

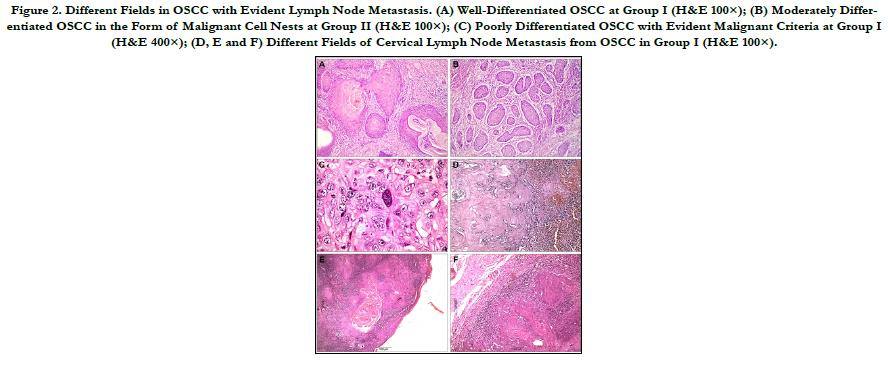

Figure 2. Different Fields in OSCC with Evident Lymph Node Metastasis. (A) Well-Differentiated OSCC at Group I (H&E 100×); (B) Moderately Differentiated OSCC in the Form of Malignant Cell Nests at Group II (H&E 100×); (C) Poorly Differentiated OSCC with Evident Malignant Criteria at Group I (H&E 400×); (D, E and F) Different Fields of Cervical Lymph Node Metastasis from OSCC in Group I (H&E 100×).

Figure 3. CD44 Expression in Different Fields of OSCC. (A) Strong Staining (+++) Group I, (B) Moderate Staining (++) Group I and (C) weak staining (+) Group II. (Immunostained 100×).

Figure 4. Different DNA Frequency Histograms. (A) High SPF (25.67%) and hyperdiploidpeak (DI= 1.12), Group I; (B) Low SPF (6.14%) and hyperdiploid peak (DI= 1.09), Group I; (C) Low SPF (16.23%) and hypodiploid peak (DI= 0.79), Group I; (D)High SPF (9. 87%) and hypodiploid peak (DI= 0.82), Group II; (E) High SPF (54.32%) and diploid peak, Group I; (F) Low SPF (7.36%) and diploid peak, Group II.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Patients with Oral Cancer with respect to CD44 Intensity and Flow Cytometric Parameters between the Study Groups.

Discussion

Oral cancerexhibits an aggressive behaviour along with a high incidence of nodal metastasis, even in the initial stages, which always

causes a poor prognosis. [20] The CSCs hypothesis states

thatCSCs exerted both regional and systemic effects on the cancer

growth and metastasis.[21] CD44 was proposed as the ideal

CSCs marker. The CSCs population identified by CD44 antibody

expression was linked and parallel with the carcinogenesis process

activity. It further contributed to aggressive cancer phenotypes.

[22] This study’s findings demonstrated a link between higher

expression levels of CD44 and cervical lymph node metastasis

of OSCC. Furthermore, this link has been shown to predict a

poor survival and prognosis in patients with cancer. The CD44

expression plays a performative role in cancer aggressiveness and

metastasis. A marked increase in the CD44 area (%) and optical

density was recorded in the examined tissues with lymph node

metastatic deposits. The marker expression demonstrated a highly

statistically value in the comparison between metastatic and nonmetastatic

lymph node OSCC. A high expression of CD44 could

provide relevant information for the high competence of malignant

cellsthat promote the progress of metastatic deposits.

In agreement with the our research results, Mirhashemi et al. observed

a higher expression of CD44 and CD24 in OSCC, and

revealed the possibility of malignant transformation.[23] Additionally,

Judd et al. noted that the weak CD44 expression caused a

delay in the carcinoma growth and metastasis.[24] Moreover, Cohen

et al.tested the CD44 expression thatpresented as a prognostic

aspect in oropharyngeal carcinomas.[25] Furthermore, comparable

results reported by de Andrade et al. identified that the

tissue cells with a strong CD44 expression had a higher capacity

to form malignance.[26] Likewise, a study oforal cancer cell lines

conducted by Ghuwalewala et al. revealed thatthe cell population

with an intense CD44 expression enhanced a more tumorigenic

potential along with invasive and metastatic skills.[27] Additionally,

Paulis et al.concluded that the CD44 expression increased the

aggressiveness of cancer cells behaviour.[28] Li et al.suggested

that intense CD44 expression correlates to the advanced tumour

grades, recurrence and poor prognosis.[29] This observation goes

in line with the results of our research. In contrast, Krump et

al. demonstrated that there are no serious differences in CD44

reactions between the different carcinoma grades in the oral cavity.

[30] This shortening in the appearance of CD44 may be attributed

to the improper selection of the examined tissues that

may have massive areas of inflammation, further leading to a false

result in the CD44 expression. Moreover, the difference in the

examined tissue and the sorting techniques with that of immunohistochemistry

for identifying the CD44 expression in tissue such

as Western blotting and flow cytometric assessments may have

validated different sorting results.

This study demonstrated that the differences in DNA ploidy was

highly statistically significant (p <0.0001) as revealed in thecomparison

between Group I (metastatic lymph node OSCC) and

Group II (non-metastatic lymph node OSCC). The research results

are compatible with El-Deftar et al.’s findings.[31] Furthermore,

Hayry et al.’s resultsindicate that the nuclear morphometric

features and analysis of DNA ploidy of the nodal tissue by FCM

mainly help as the prognostic metastatic markers of oral cancer.

[32] Supporting data published by Kamphues et al. reported that

the DI represents an independent prognostic marker both postand

preoperatively. It might become a potential tool in the preoperative

decision-making process.[33] Furthermore, Jagric et al.

concluded that FCM is a rapid, cost-effective, widely obtainable

and highly distinct method for sentinel lymph node metastases.

Therefore, it cannot be recommended as the onlytest for detecting

lymph node metastases beforesurgeries.[34] Moreover,Acosta

et al.concluded that the finding of positive aneuploid cells using

FCM strongly indicates the presence of carcinoma cells.[35]. Additionally,

Missaoui et al. showed that DI and SPF appear helpful

in making the distinction between benign and malignant lesions,

and aneuploidy appears to be more interesting in the prognosis

evaluation of these neoplasms.[36] However, Ludovini et al. do

not support the prognostic aspect of DNA ploidy to spot patients

with more aggressive tumours who are at a high risk for disease

relapse and metastases.[37] Furthermore, Zargoun et al. reported

that DNA ploidy alone was not specific and may not be a good

tool to evaluate prognosis or metastatic progression in oral cavity

carcinomas.[38] This result is in agreement with our findings,

which recorded that the collaboration between the CD44 immunohistochemical

expression and the DNA analysis by FCM was

more effective in predicting the capability of the malignant cell to

promote lymph node metastases.

Our finding showed that there was no important relationship

between the SPF of the metastatic and non-metastatic lymph

node cases. This result agrees with Zahran et al.’s results, which

expressed that theDNA aneuploidy may be a key indicator for

tumour activity and malignancy in salivary gland tumours with

no significant SPF value in evaluating tissue activity.[39] Similarly,

Pinto et al. report a borderline significance of SPF with respect

to the overall survival and loco-regional lymph node metastasis

of papillary thyroid carcinoma.[40] In different circumstances,

Pervez et al.found that the SPF was a more reliable marker in

anticipating the axillary lymph node metastases in breast carcinomas.[

41] Oya et al. also demonstrated that theDNA ploidy is

heterogeneous within a cancer, whereas SPF is relatively stable

and can be correlated with regional metastasis in oral cancer.[42]

Lymph node metastasis is a convoluted progression of events.

Initially, cancer cells penetratetheir adjacent tissues and move

throughthe lymphatic vessels. Finally, they are carried to the cervical

lymph nodes where they must be deposited and grow to form

metastatic lesions. The chance of evolution of each cell population

would be higher with heterogeneous tumours.[43, 44] At the

time of diagnosis, malignant neoplasms have undergone various

changes during progression and usually contain subpopulations

of cells with different biologic features. Obviously, aneuploid carcinomais

more heterogeneous than the diploid one in terms of

cell populations. This may be the reason for the higher incidence

of lymph node metastasis shown by the aneuploid carcinomasas

compared to the diploid one.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the immunoexpression of CD44 was found in

all the OSCC samples. The high CD44 expression was compellingand

associated with a higher stage of lymph node metastasis.

The state of DNA ploidy can possibly advance our prediction

oforal cancer strength to establishlymph node metastasis.

Further studies regarding the anticipation of the oral cancer metastasiswill

definitely increase therapeutic success while effectively

decreasing morbidity and mortality of OSCC.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

-

[1]. Canay S, Kocadereli I, Akca E. The effect of enamel air abrasion on the retention

of bonded metallic orthodontic brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop. 2000; 117: 15¬19. Pubmed PMID:10629515.

[2]. Buonocore MG. A simple method of increasing the adhesion of acrylic filling materials to enamel surfaces. J DentRes 1955; 34: 849¬853. Pubmed PMID:13271655.

[3]. Vasei F. Effect of chitosan treatment on shear bond strength of composite to deep dentin using self-etch and total-etch adhesive systems. Brazilian Dental Science. 2021;24(2).

[4]. Van Meerbeek B, Inouse S, Perdiago J, Lambrechts P, Vanherle G. Enamel and dentin adhesion. Fundamentals of Operative Dentistry. A Contemporary Approach. Chicago: Quintessence, 178-235, 2001.

[5]. Saroglu I, Aras S, Oztas D. Effect of deproteinization on composite bond strength in hypocalcified amelogenesis imperfecta. Oral Diseases 2006;12 (3): 305-308.

[6]. Aras S¸, Ku¨c¸u¨kes¸men C¸, Ku¨c¸u¨kes¸men HC. Influences of dental fluorosis and deproteinization treatment on shear bond strengths of composite restorations in permanent molar teeth. Fluoride2007; 40(4): 290-291.

[7]. Atkins CO Jr, Rubenstein L, Avent M. Preliminary clinical evaluation of dentinal and enamel bonding in primary anterior teeth. J Pedod 1986; 10: 239¬246.

[8]. Espinosa R, Valencia R, Uribe M, Ceja I, Saadia M. Enamel deproteinization and itseffect on acid etching: An in vitro study. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2008;33:13-9.

[9]. Venezie RD, Vadiakas G, Christensen JR, Wright JT. Enamel pretreatment with sodium hypochlorite to enhance bonding in hypocalcified amelogenesis imperfecta: Case report and SEM analysis. Pediatr Dent 1994;16: 433-436.

[10]. Ahuja B, Yeluri R, Baliga S, Munshi AK. Enamel deproteinization before acid etching – A scanning electron microscopic observation. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2010;35:169-72.

[11]. Espinosa R, Valencia R, Uribe M, Ceja I, Cruz J, Saadia M, et al. Resin replica in enamel deproteinization and its effect on acid etching. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2010;35:47-51.

[12]. Go´mez S, Bravo P, Morales R, Romero A, Oyarzu´n A. Resin penetration in artificial enamel carious lesions after using sodium hypochlorite as a deproteinization agent. JClin Pediatr Dent 2014;39:51-6.

[13]. Aras S, Ku¨c¸u¨kes¸men C, Ku¨c¸u¨kes¸men HC, So¨nmez IS. Deproteinization treatment on bond strengths of primary, mature and immature permanent tooth enamel. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2013;37:275-9.

[14]. Abdelmegid FY. Effect of deproteinization before and after acid etching on the surface roughness of immature permanent enamel. Niger J Clin Pract. 2018 May;21(5):591-596. Pubmed PMID: 29735859.

[15]. Hasija P, Sachdev V, Mathur S, Rath R. Deproteinizing Agents as an Effective Enamel Bond Enhancer-An in Vitro Study. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2017;41(4):280-283. PubmedPMID: 28650791.

[16]. López-Luján NA, Munayco-Pantoja ER, Torres-Ramos G, Blanco-Victorio DJ, Siccha-Macassi A, López-Ramos RP. Deproteinization of prim1/ary enamel with sodium hypochlorite before phosphoric acid etching. Desproteinización del esmalte primario con hipoclorito de sodio antes del grabado con ácido fosfórico. Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2019;32(1):29-35.

[17]. Bahrololoomi Z, Kabudan M, Gholami L. Effect of Er:YAG Laser on Shear Bond Strength of Composite to Enamel and Dentin of Primary Teeth. J Dent (Tehran).2015;12(3):163-170. Pubmed PMID:26622267.

[18]. Heyman HO, Ritter AV, Roberson TM. Introduction to composite restorations. In: Roberson TM, Heyman HO, SwiftE. Sturdevant's Art and Science of operative dentistry. St.Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 6: 216-228, 2013.Van Meerbeek B, De Munck J, Yoshida Y, Inoue S, Vargas M, et al. Buonocore memorial lecture. Adhesion to enamel and dentin: current status and future challenges. Oper Dent 2003;28: 215-235. Pubmed PMID:12760693.

[19]. Kodaka T, Kuroiwa M, Higashi S. Structural and distribution patterns of surface Prismless enamel in human permanent teeth. Caries Res 1991;25 (1): 7-20. Pubmed PMID: 2070383.

[20]. Ramakrishna Y, Bhoomika A, Harleen N, Munshi AK. Enamel deproteinization after acid etching-Is it worth the effort?. Dentistry. 2014;4(2):1-6.

[21]. Sirisha K, Rambabu T, Shankar YR, Ravikumar P. Validity of bond strength tests: A critical review: Part I. J Conserv Dent. 2014;17(4):305-311.

[22]. Van Meerbeek B, Peumans M, Poitevin A, Mine A, Van Ende A, Neves A, et al. Relationship between bond-strength tests and clinical outcomes. Dent Mater. 2010;26:e100–21. Pubmed PMID: 20006379.

[23]. Harleen N, Ramakrishna Y, Munshi AK. Enamel deproteinization before acid etching and its effect on the shear bond strength – An in vitro study. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2011;36:19-23. Pubmed PMID:22900439.