The Assessment Of The Antibacterial Effect Of Diode Laser Versus Nanosilver Fluoride On Streptococcus Mutans Count Of Oral Biofilm Of Primary Teeth

Sihem Hajjaji1*, Rihab Dakhli2, Hayet Hajjemi1, Abdellatif Boughzela1

1 Department of Dentistry, Farhat Hached University Hospital, Sousse, Tunisia.

2 Fixed Prosthesis Department, Dental School, Monastir, Tunisia.

*Corresponding Author

Sihem Hajjaji,

Department of Dentistry, Farhat Hached University Hospital, Sousse, Tunisia.

E-mail: sihemhajjaji@gmail.com

Received: September 19, 2021; Accepted: November 17, 2021; Published: November 20, 2021

Citation: Sihem Hajjaji, Rihab Dakhli, Hayet Hajjemi, Abdellatif Boughzela. Zirconia In The Service Of Anterior Aesthetic Restorations. Int J Dentistry Oral Sci. 2021;8(11):5057-5060.doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2377-8075-210001018

Copyright: Sihem Hajjaji©2021. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Introduction: Zirconia appears in odontology fifteen years ago under the form of a screed covered with feldpathic ceramic,

as an alternative to the ceramic-metal crown. The success of zirconia stems from its biocompatibility and aesthetic potential in

combination with optimized mechanical properties. For years, zirconia was the benchmark for the restoration of the posterior

sector. Today translucent zirconia are offered to satisfy aesthetic demands even at the previous level

Observation: The 54-year-old HA patient consulted for the replacement of her old ceramic-metal bridge in the anterior sector.

Its motif was both aesthetic and functional. The therapeutic choice was directed towards the creation of metal ceramic

bridge with a zirconia coping. The clinical steps necessary for this prosthetic design will be detailed step by step.

Discussion: Several ceramics are now available to us for aesthetic anterior restorations. However, the choice of the appropriate

ceramic is not only guided by aesthetic needs. Other parameters must be taken into consideration such as the situation of

the finish line, the height of the stumps ... Zirconia may not seem like the ideal ceramic for anterior restorations. However,

when the case requires, we can opt for an "improved" zirconia giving wide aesthetic satisfaction.

2.Introduction

3.Materials and Methods

3.Results

4.Discussion

5.Conclusion

5.References

Keywords

Zirconia; Aesthetics; Translucency; Opacity; Density.

Introduction

Zirconia is one of the materials that has undergone particularly

rapid and significant development, particularly with the democratization

of computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/

CAM). For years, zirconia was considered to be the material of

choice for the development of infrastructures at the later level

and this thanks to its excellent mechanical properties.

In recent years, the use of zirconia has shifted to the prior sector.

In this indication, the reflective nature of zirconia posed a major

aesthetic problem and it therefore became essential to improve its

translucency.

Translucent zirconia with strengths of around 800MPa were then

developed for posterior monolithic restorations. Today very high

translucency versions are available. The latter are experiencing

exponential development and allow stunning anterior aesthetics,

even in the case of restorations without layering.

Observation

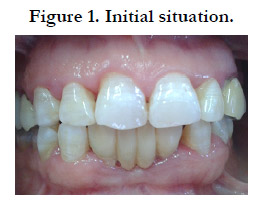

Patient HA, aged 54, consulted our fixed prosthesis unit for mobility

of her ceramic-metal bridge made almost ten years ago (fig.

1). During questioning, the patient expressed her dissatisfaction

with the aesthetic appearance of her bridge.

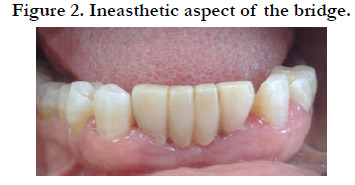

Oral examination revealed a ceramic-metal bridge replacing the

two mandibular central incisors and resting on the two mandibular

lateral incisors. The general morphology of the bridge did not

meet standard aesthetic standards for an anterior fixed prosthesis.

A shift of the interincisal line was noted with no contact point on

the distal side.

The bridge presented degree 3 of mobility with pain felt at the

slightest touch. Our course of action was first of all directed towards

atraumatic removal of the bridge and evaluation of the

residual support teeth.

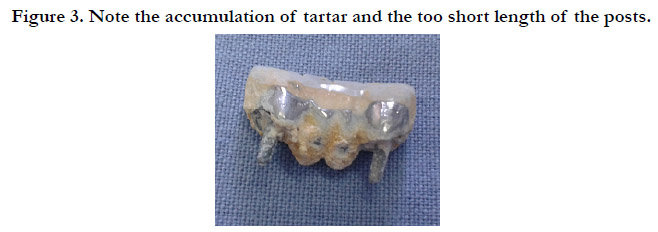

The condition of the dismantled bridge explained the increased

mobility justified by a lack of retention due to the use of too short posts that did not sufficiently exploit the length of the

roots. A deposit of tartar on the entire gingival surface of the

pontic explained the inflammatory state of the edentulous ridge

(fig. 3). The state of the residual supporting teeth justified their

extraction: sub-total disrepair (fig. 4a, b), support periodontal reduced

with a longitudinal fracture at the level of 32 (fig. 5). After

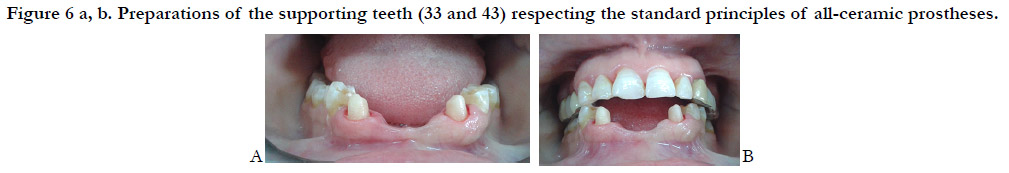

comparing all the data, the prosthetic choice turned towards the

creation of a ceramic-ceramic bridge with zirconia copings replacing

the four mandibular incisors and taking 33 and 43 as supporting

teeth. The clinical protocol began with the preparation of

the supporting teeth (fig 6.a, b). This preparation met the main

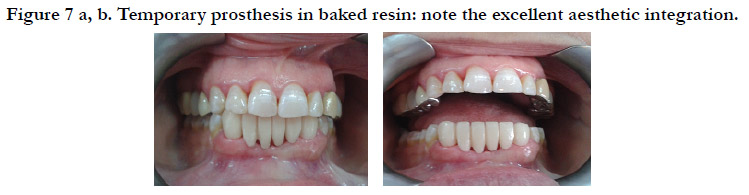

principles of all-ceramic prostheses. Subsequently, a temporary

prosthesis in baked resin was used to protect the prepared teeth.

At this timeout period, the provisional prosthesis was modified

several times depending on the patient's complaints, both aesthetically

and functionally. At the end of this phase, the patient clearly

expressed her full satisfaction, which enabled us to consider this

bridge as a prototype for her final prosthesis (Fig. 7a, b). The

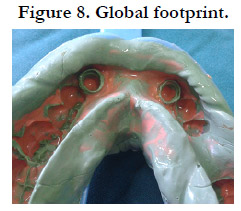

imprint of the preparations was taken during the same session,

guaranteeing a faithful reproduction of the details (fig. 8).

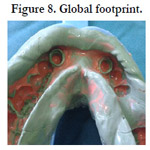

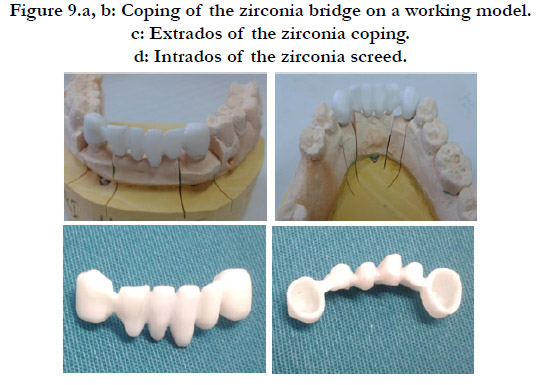

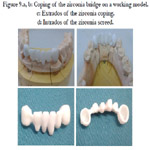

The zirconia coping of the bridge was tested on its model, then in

the mouth: the points that were verified are the adaptation of the

cervical limits, the retention and stability of the coping, as well as

the space left for the veneering ceramic. (fig. 9.a, b, c, d).

The choice was made on the shade of the two maxillary central

incisors, since the patient planned to redo her two right and

left maxillary lateral prostheses, and in order to optimize the final

aesthetic result, an external teeth whitening was planned. The finished

bridge was sealed using CVIMAR. The final aesthetic result

was very satisfactory for both the patient and the whole team (Fig.

10).

Figure 6 a, b. Preparations of the supporting teeth (33 and 43) respecting the standard principles of all-ceramic prostheses.

Figure 9.a, b: Coping of the zirconia bridge on a working model.

c: Extrados of the zirconia coping.

d: Intrados of the zirconia screed.

Discussion

In the case below, the choice of ceramic material was a delicate

task. Indeed, the multiplicity of materials available today leads us

to make a precise choice in order to best respond to the clinical

situation that presents itself to us. It was through a critical analysis

of the interests and limitations of zirconia that we made our

choice:

Aesthetic interest: This is the major interest of restoration. Zirconia

meets the "aesthetic" specifications. However, it is important

to note that this is not the ideal framework ceramic in the anterior

sector due to its low translucency. Indeed, it is the most opaque

ceramic. This opacity is essential.

It is the result of the ratio between reflected light intensity and transmitted light intensity. The more opaque the material, the less

light is transmitted. Currently, laboratories propose to color zirconia

copings (either by dipping or by applying a dye with a brush).

This allows increased mimicry with the different forms of coronary

preparations intended to receive all-ceramic reconstructions

with a zirconia framework. Other laboratories suggest covering

the screed with an "opaque liner" in order to reduce this luminosity.

Several coats can be applied in order to adapt the color with

the adjacent teeth, and this, for an optimal aesthetic result.

Other labs, pancreatic zirconia, change its composition by lowering

the proportion of Al2O3, making the zirconia semi-transparent.

For other manufacturers, the thickness of the framework is

the most important component of aesthetic aspect and the translucency

of the prosthesis. Indeed, a 0.5mm thick lava zirconia

coping will have the same translucency as an empress II ceramic

0.8mm. Beyond this thickness, the opacity gradually increases.

As we have seen therefore, several techniques are proposed today

to improve the translucency of zirconia. However, it should

be noted that the aesthetic result of a prosthesis is always very

subjective, whether in terms of color or shape. Indeed, the experience

of the operators (practitioner and prosthetist) is essential in

the final success and integration of the restoration.

The observation of the natural shade and shape of teeth and their

transmission to the laboratory is essential. Modern communication

techniques: digital photographs and transmission via the Internet,

constitute an important contribution. But the artistic sense

of the prosthetist, his skill and his experience remain decisive for

the final result. In addition, the observation of many parameters

such as: the smile line, the type of periodontium, during the clinical

examination is a step as essential as the choice of material in

the aesthetic success of the project. zirconia is a parameter of this

success. It is of major interest in its use in the prior sector.

Conclusion

Zirconia is considered today as an essential material in our therapeutic

arsenal. Well - known for its mechanical resistance, research

focused, with the advent of CAD / CAM, on zirconia prostheses

with markedly improved aesthetics. Zirconia became thus a credible

option both in the posterior sector and in the anterior sector.

However, it should not be considered that its evolution is complete

and its use i without risks. Certain difficulties persist; they

must be mastered in order to be able to make zirconia a material

of choice.

References

-

[1]. Piwowarczyk A, Lauer HC, Sorensen JA. The shear bond strength between

luting cements and zirconia ceramics after two pre-treatments. Oper Dent.

2005 May-Jun;30(3):382-8. PubMed PMID: 15986960.

[2]. Souza R, Barbosa F, Araújo G, Miyashita E, Bottino MA, Melo R, Zhang Y. Ultrathin Monolithic Zirconia Veneers: Reality or Future? Report of a Clinical Case and One-year Follow-up. Oper Dent. 2018 Jan/Feb;43(1):3-11. PubMed PMID: 29284106.

[3]. Preis V, Weiser F, Handel G, Rosentritt M. Wear performance of monolithic dental ceramics with different surface treatments. Quintessence Int. 2013 May;44(5):393-405. PubMed PMID: 23479579.

[4]. Edelhoff D, Sorensen J. Light transmission through all-ceramic framework and cement combinations. InJournal of Dental Research 2002 Mar 1 (Vol. 81, pp. A234-A234). 1619 DUKE ST, ALEXANDRIA, VA 22314-3406 USA: INT AMER ASSOC DENTAL RESEARCHI ADR/AADR.

[5]. Zhang Y, Lawn BR. Novel Zirconia Materials in Dentistry. J Dent Res. 2018 Feb;97(2):140-147. PubMed PMID: 29035694.

[6]. Carrabba M, Keeling AJ, Aziz A, Vichi A, Fabian Fonzar R, Wood D, Ferrari M. Translucent zirconia in the ceramic scenario for monolithic restorations: A flexural strength and translucency comparison test. J Dent. 2017 May;60:70-76. PubMed PMID: 28274651.

[7]. Manauta J, Salat A. Layers, chapter 10. Quintessence book. 2012. [8]. Raigrodski AJ. Contemporary all-ceramic fixed partial dentures: a review. Dental Clinics. 2004 Apr 1;48(2):531-44.

[9]. Uludag B, Usumez A, Sahin V, Eser K, Ercoban E. The effect of ceramic thickness and number of firings on the color of ceramic systems: an in vitro study. J Prosthet Dent. 2007 Jan;97(1):25-31.PubMed PMID: 17280888.

[10]. Bazos P, Magne P. Bio-emulation: biomimetically emulating nature utilizing a histo-anatomic approach; structural analysis. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2011 Jan 1;6(1):8-19.

[11]. Manicone PF, Rossi Iommetti P, Raffaelli L. An overview of zirconia ceramics: basic properties and clinical applications. J Dent. 2007 Nov;35(11):819- 26. PubMed PMID: 17825465.

[12]. Raffaelli L, Iommetti PR, Piccioni E, Toesca A, Serini S, Resci F, Missori M, De Spirito M, Manicone PF, Calviello G. Growth, viability, adhesion potential, and fibronectin expression in fibroblasts cultured on zirconia or feldspatic ceramics in vitro. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A: An Official Journal of The Society for Biomaterials, The Japanese Society for Biomaterials, and The Australian Society for Biomaterials and the Korean Society for Biomaterials. 2008 Sep 15;86(4):959-68.

[13]. Porstendörfer J, Reineking A, Willert HC. Radiation risk estimation based on activity measurements of zirconium oxide implants. J Biomed Mater Res. 1996 Dec;32(4):663-7. PubMed PMID: 8953157.

[14]. Covacci V, Bruzzese N, Maccauro G, Andreassi C, Ricci GA, Piconi C, Marmo E, Burger W, Cittadini A. In vitro evaluation of the mutagenic and carcinogenic power of high purity zirconia ceramic. Biomaterials. 1999 Feb;20(4):371-6. PubMed PMID: 10048410.

[15]. Silva VV, Lameiras FS, Lobato ZI. Biological reactivity of zirconia-hydroxyapatite composites. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;63(5):583-90. PubMed PMID: 12209904.

[16]. Kohal RJ, Weng D, Bächle M, Strub JR. Loaded custom-made zirconia and titanium implants show similar osseointegration: an animal experiment. J Periodontol. 2004 Sep;75(9):1262-8. PubMed PMID: 15515343.

[17]. Kou W, Molin M, Sjögren G. Surface roughness of five different dental ceramic core materials after grinding and polishing. J Oral Rehabil. 2006 Feb;33(2):117-24. PubMed PMID: 16457671.

[18]. Jung RE, Sailer I, Hämmerle CH, Attin T, Schmidlin P. In vitro color changes of soft tissues caused by restorative materials. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2007 Jun;27(3):251-7. PubMed PMID: 17694948.

[19]. Saldaña L, Méndez-Vilas A, Jiang L, Multigner M, González-Carrasco JL, Pérez-Prado MT, González-Martín ML, Munuera L, Vilaboa N. In vitro biocompatibility of an ultrafine grained zirconium. Biomaterials. 2007 Oct;28(30):4343-54. PubMed PMID: 17624424.