Predictors of Dental Care Utilization in School Children in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia

Amal Aqeeli1,2*, Alla T. Alsharif2, Estie Kruger3, Marc Tennant4

1 International Research Collaborative, Oral Health and Equity, School of Human Sciences, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, Australia.

2 Preventive Dental Sciences, Taibah University Dental College and Hospital, Madinah, Saudi Arabia.

*Corresponding Author

Amal Aqeeli,

International Research Collaborative, Oral Health and Equity, School of Human Sciences, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, Australia.

Tel: +61432025197

E-mail: amal.aqeeli@research.uwa.edu.au

Received: October 19, 2021; Accepted: November 10, 2021; Published: November 20, 2021

Citation: Amal Aqeeli, Alla T. Alsharif, Estie Kruger, Marc Tennant. Predictors of Dental Care Utilization in School Children in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia. Int J Dentistry Oral Sci. 2021;8(11):5027-5032. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2377-8075-210001013

Copyright: Amal Aqeeli©2021. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Aim: To explore the factors influencing dental care utilization including sociodemographic characteristics, and oral health

need in 9-12-year-old school children in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia (SA).

Methods: A stratified random sample was applied to select 10 schools in Al Madinah, SA and a total of 1000 students aged

9-12 years were included in the study. Information on sociodemographic factors and dental care utilization were collectedusing

and oral health related quality of life was recorded using the World Health Organization (WHO) questionnaire. A multiple

logistic regression model was used to examine the factors associated with dental care utilization.

Results: Almost a quarter of all participants (23.8%), have never received dental care before. Pain or trouble with teeth was

the most common reason for visiting the dentist (49.4%), while only 11.8% visited the dentist for routine check-up. Thepercentages

of both missing school, and difficulty in eating due to oral health problems, were significantly higher among those

who received dental care. Children from low-income families had a reduced likelihood of receiving dental care relative to

children from higher and middle-income families (OR=0.571, P=0.014). Children who have caries and who reported having

toothache in the past 12 months were more likely to visit the dentist (OR=1.599, P=0.028) &(OR=2.188, P>0.001).

Conclusion: Dental care utilization is primarily driven by symptomatic dental care. The prevalence of dental utilization was

relatively high among children from high- and middle-income families, children who have caries and children who reported

having toothache in the past 12 months.

2.Introduction

3.Materials and Methods

3.Results

4.Discussion

5.Conclusion

5.References

Keywords

Dental Care Utilization; Dental Care; Check-Up; Caries.

Introduction

Dental caries remains the most predominant oral disease in childhood

despite its decline worldwide [1]. Dental care utilization is

an essential component for preventing caries and improving oral

health and well-being.Understanding the factors affectingutilizationhas

been atopic of focus in dental public health.

Several studies have highlighted different reasons of utilization or

underutilization among children. Findings suggest that thereless

dental care use by males, racial minorities, and when lack of accessibility

and affordability exist [2, 3]. Children whose parents have

lower education and awareness and with low socioeconomic status

also underutilize dental care [4, 5]. Other investigations have

identified geographical location and distribution of the dental

care services as other important factors associated with the use

of dental care [6].

Dental care utilization patterns can also be influenced by the presence

of either normative or self-perceived oral health care needs

[7]. In addition, dental carerelated anxiety and fear and reduced

quality of life are also important factors that influence the pattern

of visiting the dentist; those who have dental anxiety end

up avoiding going to the dentist while those who have poor oral

health related quality of life visited a dentist with higher frequency

[5].

Limited data, however, are available on these factors related to

dental care utilization in SA. Saudi Arabia has a great burden of dental caries and a low rate of dental care utilization compared to

developed [8, 9]. In SA, only a small percentage of children visit

the dentist for regular check-ups while the majority go to the dentist

only because of pain, despite the free of charge dental services

provided by the government [10]. Data from El Bcheraoui et al

showed that only 11.5% visited the dentist regularly while AlAgili

et al reported thatone in four children have never visited a dentist

[11, 12]. Perceived barriers to dental care for Saudi children who

never went to a dentist included oral health illiteracy, dentist-related,

financial and transportation [12], while encouraging factors to

utilizing dental care are quality of dental care, reasonable fees for

dental services and close location of dental clinics [13].

Identifying factors related to dental care utilizationwould help in

future public policy making and public health interventions. This

study aimed to investigate the factors associated with dental care

utilization including sociodemographic characteristics, and oral

health need in 9-12 years old schoolchildren in Al-Madinah, SA.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Approval

To access the de-identified oral health survey data, ethical approval

was obtained from the Taibah University Ethics Committee

in Al-Madinah, SA and ethical clearance from the University

of Western Australia Ethics Committee was attained. The study

was conducted in accordance with the principles of the World

Medical Association of Helsinki. Children’s parents’ consent was

obtained, as well as a child agreement to participate, prior to interview

and examination. Participation in the study was voluntary

and every questionnaire and examination were anonymous.

Study design and data collection

Oral health survey data was collected by calibrated and trained

staff from the University of Taibah, Department of Preventive

Dental Sciences (DPDS). The survey and oralexaminations were

carried out in accordance with the international standards established

by the World Health Organization [14]. Instructors with

previous experience in oral health surveys and examination following

WHO’s guidelines directed the training.

As for the selection of participating schools, a stratified random

sampling design was applied to select schools. Schools were stratified

based on socioeconomic level of the school districtbased

on the knowledge of the disadvantage of the area; high and low

socio-economic. Afterwards, five schools from each stratum were

randomly selected and included in the survey. Thus, the stratification

of schools was done on area level, however, to carry out the

analysis with more specific data, an indication of individual level

of socio-economic status was also included based on family data.

Both levels included public and private schools.

Prior to each school visit, information sheets and questionnaires

were sent to all parents of 9-12-year-olds in the schools to invite

participation and obtain consent. All 9-12-year-old students who

attended the selected schools on the day of the survey, and whose

parents returned the consent form were included in the survey.

One thousand two hundredsixty-five students were invited to the

survey and the response rate was 83%, so it ended up with 1049

students. Uncompleted questionnaires were excluded from the

study, and it ended up with 1000 students. The final number of

participants per each school ranged from 98-119 adding up to

1000. The children were interviewed to obtain sociodemographic

data, and information on oral health need and quality of life using

the WHO oral health questionnaire for children.

Oral examinations were performed by 10 calibrated and trained

examiners following the standardized WHO Oral Health Survey

assessment form for oral health surveys [14]. Caries experience

was measured clinically by the dental examiners and recorded as

present if the child had at least one tooth as decayed, filled or was

missing due to caries. The interview questionnaire incorporated

information on sociodemographic characteristics, utilization of

dental care, and child self- perception of oral health.

Study Variables

The main outcome of interest in this study was dental care utilization

and was measured using a question about the frequency of

visiting the dentist within the past 12 months (once, twice, three

times, four times or more, or “I have never received dental care”).

A new binary outcome variable was created with all those who

reported dental visits as one category, and all other responses as a

second category (visited the dentist and never visited the dentist).

Independent variables comprised of oral health need variables

which included caries experience (examined need), self-perception

of oral health and toothache in the past 12 months (perceived

need). Caries experience was expressed as (yes or no) for

children with/without any caries experience.

Self-perception of oral health was measured by asking the child

to rate their perception of their oral health (excellent; good; faire;

poor; very poor or I don’t know) and for analytical purposes,

good and fair were merged to good, and poor and very poor were

also merged to poor.

Toothache in past 12 months were measured by asking the child

how often during the past 12 months “did you have toothache

or feel discomfort due to your teeth” (often; occasionally; rarely;

never or do not know). Often, occasionally, and rarely were

merged to yes, and never were recorded asno. Reduced quality

of life due to oral health problems was measured on appearance,

smiling, bullying, missing school and eating. For each variable, the

child had to choose (yes or no).

Sociodemographic variables included age, gender, school type,

and family occupation. Age was categorized as two groups: 9-10

years old and 11-12 years old. The type of school was dichotomized

as public or private schools. To determine level of socioeconomic

status, parents occupations were used as a proxy of

family monthly income, and divided into three categories, low,

medium and high, as described elsewhere [15].

Statistical Analysis

Dental care utilization was analyzed across sociodemographic,

oral health need and reduced quality of life due to oral health

problems. The difference between groups was assessed by using

Chi-square and significance levels was set at P value = 0.05. Logistic

regression model was carried out with dental care utilization

as the dependent variable and adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and oral health. Software used for data entry (Microsoft

Office Excel 2018 for Windows, Microsoft Corporation,

Redmond, WA, USA) and all statistical tests were conducted using

IBM SPSS software (ver.25.0; IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Of 1265 students aged 9-12 years old, a total of 1000 students

with completed questionnaires and oral examinations were analyzed

and included in the study (83% response rate).

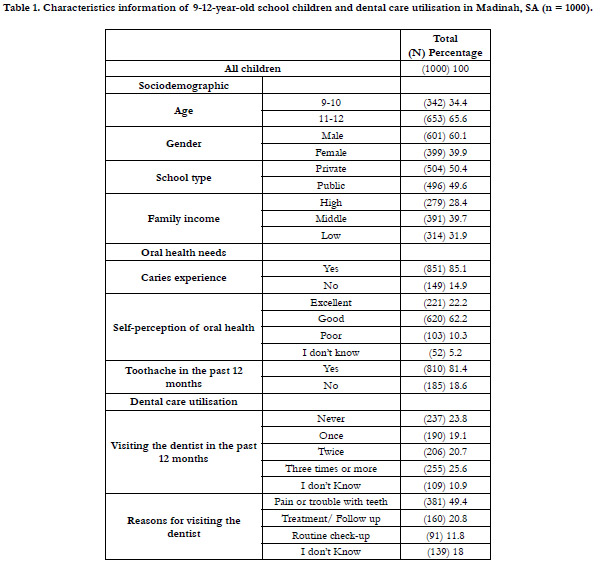

Table 1 presents characteristics information for the sample and

the distribution of the variables across dental care utilization.

More than half of the participants (65.6%) were between 11-12

years old. Of the participants, 39.9% were females and 60.1%

were male. There was a high prevalence of dental caries experience

(85.1%), and 81.4% reported toothache in the past 12

months, however, two third of the participants were satisfied with

their oral health; and 62.2% reported good oral health. Pain or

trouble with teeth was the most common reason for visiting the

dentist (49.4%) while only 11.8% visited the dentist for routine

check-up.

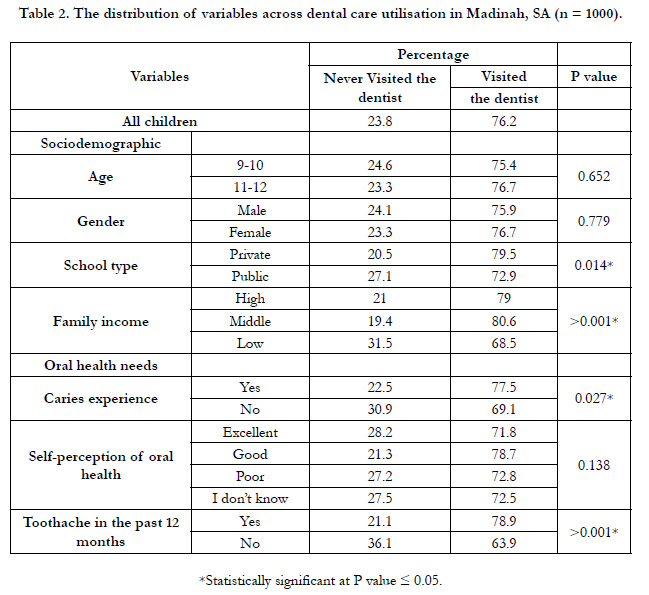

The percentage of children who have never received dental care

was 23.8%, and of these, a higher percentage attended public

schools in contrast to private schools (27.1% Vs 20.5%; P=0.014)

(Table 2). Significantly more children from low-income families

had not received dental care (31.5%; P=>0.001).

Among oral health need, the percentage of children who received

dental care was significantly higher among those who have caries

experience and reported toothache in the past 12 months

(P=0.027 and P>0.001 respectively).

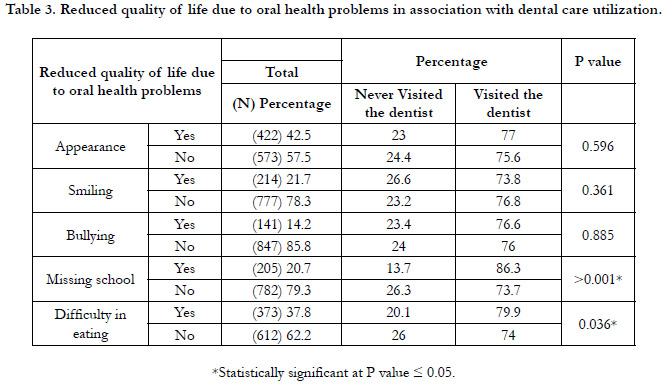

As presented in Table 3, reduced quality of life due to oral health

problems was highest in the aspect of feeling embarrassed due to

appearance of teeth (49.5%). The percentages of both a): missing

school; and b) difficulty in eating due to oral health problems,

were significantly higher among those who received dental care

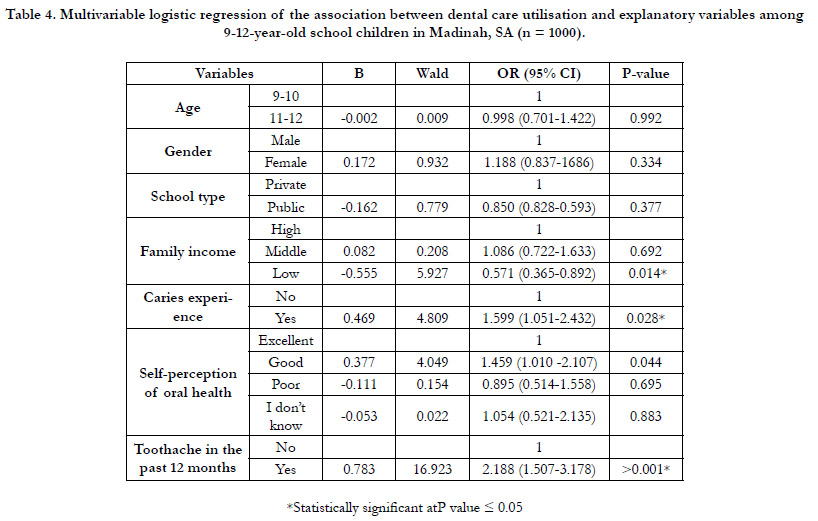

(86.3%; P>0.001 and 79.9%; P=0.036 respectively). The results from the multiple logistic regression model are presented

in Table 4. After controlling for all other variables in the

model, children from low-income families had a reduced likelihood

of receiving dental care relative to children from higher

and middle-income families (OR=0.571; 95% CI: 0.365-0.892,

P=0.014). Children who have caries were more likely to visit the

dentist compared to those who don’thave caries OR=1.599; 95%

CI: 1.051-2.432, P=0.028), and children who reported having

toothache in the past 12 months were more likely to visit the dentist

(OR=2.188 95% CI:1.507-3.178, P>0.001).

Table 1. Characteristics information of 9-12-year-old school children and dental care utilisation in Madinah, SA (n = 1000).

Table 3. Reduced quality of life due to oral health problems in association with dental care utilization.

Table 4. Multivariable logistic regression of the association between dental care utilisation and explanatory variables among 9-12-year-old school children in Madinah, SA (n = 1000).

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the factors associated

with dental care utilization among 9- to 12-year-old school children

in Al-Madinah, SA. The results indicate that the strongest

predictors of dental care utilization were family income, having

caries, and experiencing toothache.

In our study ‘s sample population, 23.8% or nearly a quarter never

received dental care in the past. Notably, this result is in agreement

with other studies conducted in SA. To elucidate, Al Agili et

al. reported that 26% of their study sample in Jeddah, SA never

visited the dentist previously [12]. After controlling for other variables,

our findings indicated that the greater the oral health need

for dental care expressed in having caries or experiencing toothache,

the higher the use of dental services among children. Our

results agree with AlHumaid et al., who found that significantly

higher odds of pain were associated with visiting when in dental

pain [10]. In this study, reduced quality of life due to oral health

problems was found to be one of the factors associated with visits

to the dentist. This finding supports the work of Goettems

et al.,who also found that individuals who had poor oral healthrelated

quality of life visited dentists more frequently [5].

Among those who visited the dentist previously,a very small

percentage of children visited regularly for routine check-ups

(11.8%). Meanwhile, majority visited the dentist to address pain or

to undergo follow-up. This is in line with other studies conducted

in SA [10, 11, 16]. Symptomatic dental visits seem to determine

dental care utilization among Saudi children despite thefree access

to dental care in the country and the increasing efforts to promote

preventive dental care visits among children. This irregular pattern

in the use of dental health services contributes to the high

prevalence of untreated dental caries in the population, where it

persists as the main dental health problem among Saudi children

[17]. Herein, it should be highlighted that the prevalence of dental

caries was very high (85.1%).

The reasons why children never visited the dentist before could

be attributed to several factors, includinglack of geographic accessibility.

In a study by Gafar et al., it was reported that far-situated

dental services was one of the perceived barriers to dental

visits [18]. In addition,one of the common reasons that lead to

the avoidance of dental care utilizationis dental-related anxiety.

Dental anxiety leads to avoidance behavior and is associated with

higher caries morbidity and need for oral rehabilitation [19].

Furthermore, parents’ education and awareness areimportant factors

that influence dental service use by children [20]. In a study

by Alshammary et al., 58.3% of the respondents reported that

they would take their children to the dentist only if the child is

experiencing pain, while only 13% of the parents stated that they

take their children to the dentist twice a year [21]. Another study

reported that parental oral health illiteracy was the predominant

barrier to dental care use among children [12].

The quality of the provision of dental care plays a crucial role in

determining its utilization. It could influenceparents’satisfaction

which,in turn, could be considered as another perceived barrier

to children’sutilization of the free dental services provided by the

government. The results of a previous study found that parents

of children who never visited the dentist or who needed dental

care in the past 12 month but could not get it reported problems

with the dental health system, which included lack of a dentist or

a specialized dentist in the community, difficulty in getting a dental

appointment, and long wait times at the clinic [12]. In addition,

the unavailability of dentists, long waiting listsand a perception of low quality of dental care in the government’s dental clinics

compared with private dental offices were reported as barriers of

access to dental services in SA [22, 23].

It has been well documented that children from a low socioeconomic

status tend to have the greatest need for and the lowest accessto

dental services [24]. Our findings agree with the literature,

aschildren from low-income families were less likely to receive

dental care services than did children from high income families.

Similar findings have been observed in other countries like Japan

and Canada [25, 26].

These data must be interpreted with caution because the findings

are limited by the cross-sectional nature of this study which does

not support temporality or causality. Bearing in mind that the

study sample was restricted to 9- to 12-year-old primary school

children in Al-Madinah City, caution should be practiced in generalizing

the results to the entire country. However, considering

the cultural homogeneity and urbanity of the area, weexpect our

estimates to be relevant to the general child population in SA.

Moreover, we used self- reported data and father’s and mother’s

occupations as a proximity for family, which this could introduce

bias. And it is important to bear in mind the possible bias in these

responses.

Our findings emphasize that the free access to dental care in SA

does not guarantee theutilization of dental care by everyone who

is in need thereof. This study has identified the predictors of the

utilization of dental care services, which could help in formulating

strategies that are specifically geared towards the population

that is in need of dental care. Future studies are recommended to

further examine the underlying barriers to the utilization of dental

services by children, including the use of geographic analysis to

assess distribution and accessibility of dental services [27]. This

information can be used to inform the enactment of policiesand

todevelop appropriate and specific interventions to increase dental

care utilization among children.

Data Availability Statement

That data that support the findings of this study are available

from Department of Preventive Dental Sciences at Taibah University

Dental College and Hospital, Taibah University, Saudi Arabia,

upon reasonable request.

References

-

[1]. Frencken JE, Sharma P, Stenhouse L, Green D, Laverty D, Dietrich T.

Global epidemiology of dental caries and severe periodontitis - a comprehensive

review. J ClinPeriodontol. 2017 Mar;44Suppl 18:S94-S105. PubMed

PMID: 28266116.

[2]. Chen M, Wright CD, Tokede O, Yansane A, Montasem A, Kalenderian E, Beaty TH, Feingold E, Shaffer JR, Crout RJ, Neiswanger K, Weyant RJ, Marazita ML, McNeil DW. Predictors of dental care utilization in northcentral Appalachia in the USA.Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2019 Aug;47(4):283-290. PubMed PMID: 30993747.

[3]. Tchicaya A, Lorentz N. Socioeconomic inequalities in the non-use of dental care in Europe. Int J Equity Health. 2014 Jan 29;13:7. doi: 10.1186/1475- 9276-13-7. PubMed PMID: 24476233.

[4]. Edelstein BL, Chinn CH. Update on disparities in oral health and access to dental care for America's children. AcadPediatr. 2009 Nov-Dec;9(6):415-9. PubMed PMID: 19945076.

[5]. Goettems ML, Ardenghi TM, Demarco FF, Romano AR, Torriani DD. Children's use of dental services: influence of maternal dental anxiety, attendance pattern, and perception of children's quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012 Oct;40(5):451-8. PubMed PMID: 22537392.

[6]. Yuen A, Rocha CM, Kruger E, Tennant M. The equity of access to primary dental care in São Paulo, Brazil: A geospatial analysis. Int Dent J. 2018 Jun;68(3):171-175. PubMed PMID: 28913887.

[7]. Piovesan C, Antunes JL, Guedes RS, Ardenghi TM. Influence of self-perceived oral health and socioeconomic predictors on the utilization of dental care services by schoolchildren. Braz Oral Res. 2011 Mar-Apr;25(2):143-9. PubMed PMID: 21359493.

[8]. M Orfali DS, S Aldossary DM. Utilization of Dental Services in Saudi Arabia: A Review of the Associated Factors. Saudi J Oral Dent Res 2020;05:147–9.

[9]. John JR, Mannan H, Nargundkar S, D'Souza M, Do LG, Arora A. Predictors of dental visits among primary school children in the rural Australian community of Lithgow. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017 Apr 11;17(1):264. PubMed PMID: 28399864.

[10]. AlHumaid J, El Tantawi M, AlAgl A, Kayal S, Al Suwaiyan Z, Al-Ansari A. Dental Visit Patterns and Oral Health Outcomes in Saudi Children. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2018 May-Aug;6(2):89-94. PubmedPMID: 30787827.

[11]. El Bcheraoui C, Tuffaha M, Daoud F, Kravitz H, AlMazroa MA, Al Saeedi M, Memish ZA, Basulaiman M, Al Rabeeah AA, Mokdad AH. Use of dental clinics and oral hygiene practices in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013.Int Dent J. 2016 Apr;66(2):99-104. PubMed PMID: 26749526.

[12]. Al Agili DE, Farsi NJ. Need for dental care drives utilisation of dental services among children in Saudi Arabia. Int Dent J. 2020 Jun;70(3):183-192. PubMed PMID: 31912900.

[13]. Al-Hussyeen AJ. Factors affecting utilization of dental health services and satisfaction among adolescent females in Riyadh City. Saudi Dent J. 2010 Jan;22(1):19-25. PubMed PMID: 23960475.

[14]. World Health Organization. Oral health surveys: basic methods. Fifth Edit. 2013.

[15]. Kassim S, Bakeer H, Alghazy S, Almaghraby Y, Sabbah W, Alsharif A. Socio- Demographic Variation, Perceived Oral Impairment and Oral Impact on Daily Performance among Children in Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Jul 10;16(14):2450. PubMed PMID: 31295837.

[16]. Alayadi H, Bernabé E, Sabbah W. Examining the relationship between oral health-promoting behavior and dental visits. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2019 May-Jun;13(3):40-43. PubMed PMID: 31123439.

[17]. Al Agili DE. A systematic review of population-based dental caries studies among children in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J. 2013 Jan;25(1):3-11. Pub- Med PMID: 23960549.

[18]. Gaffar BO, Alagl AS, Al-Ansari AA. The prevalence, causes, and relativity of dental anxiety in adult patients to irregular dental visits. Saudi Med J. 2014 Jun;35(6):598-603. PubMed PMID: 24888660.

[19]. Eitner S, Wichmann M, Paulsen A, Holst S. Dental anxiety--an epidemiological study on its clinical correlation and effects on oral health. J Oral Rehabil. 2006 Aug;33(8):588-93. PubMed PMID: 16856956.

[20]. Badri P, Saltaji H, Flores-Mir C, Amin M. Factors affecting children's adherence to regular dental attendance: a systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014 Aug;145(8):817-28. PubMed PMID: 25082930.

[21]. Alshammary F, Aljohani FA, Alkhuwayr FS, Siddiqui AA. Measurement of Parents' Knowledge toward Oral Health of their Children: An Observational Study from Hail, Saudi Arabia. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2019 Jul 1;20(7):801-805. PubMed PMID: 31597799.

[22]. Alshahrani A, Raheel S. Health-care System and Accessibility of Dental Services in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: An Update. J Int Oral Heal 2016;8:883– 7.

[23]. Al-Jaber A, Da'ar OB. Primary health care centers, extent of challenges and demand for oral health care in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016 Nov 4;16(1):628. PubMed PMID: 27809919.

[24]. Reda SF, Reda SM, Thomson WM, Schwendicke F. Inequality in Utilization of Dental Services: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2018 Feb;108(2):e1-e7. PubMed PMID: 29267052.

[25]. Nishide A, Fujita M, Sato Y, Nagashima K, Takahashi S, Hata A. Income- Related Inequalities in Access to Dental Care Services in Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 May 12;14(5):524. PubMed PMID: 28498342.

[26]. Ramraj C, Sadeghi L, Lawrence HP, Dempster L, Quiñonez C. Is accessing dental care becoming more difficult? Evidence from Canada's middle-income population.2013;8(2):e57377. PubMed PMID: 23437378; PMCID: PMC3577722.

[27]. Alsharif AT, Kruger E, Tennant M. Identifying and prioritising areas of child dental service need: a GIS-based approach. Community Dent Health. 2016 Mar;33(1):33-8. PubMed PMID: 27149771.