Tumor Thickness and Cervical Nodal Metastasis in N0 Oral Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients: A Prospective Study

Samer issa1, Omar Heshmeh2, Issam Alameen3, Zuhair Al-Nerabieah4*

1 PhD Candidate, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, Damascus University.

2 Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, Damascus University.

3 Professor, Department of Otolaryngology, Faculty of Medicine -Al Mouwasat University Hospital- Damascus University.

4 PhD Candidate, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Damascus University, Damascus, Syria

*Corresponding Author

Zuhair Al-Nerabieah,

PhD Candidate, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Damascus University, Damascus, Syria.

E-mail: Zuhairmajid@gmail.com

Received: October 05, 2021; Accepted: October 28, 2021; Published: November 03, 2021

Citation: Samer Issa, Omar Heshmeh, Issam Alameen, Zuhair Al-Nerabieah. Tumor Thickness and Cervical Nodal Metastasis in N0 Oral Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients: A Prospective Study. Int J Dentistry Oral Sci. 2021;8(10):4897-4901. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2377-8075-21000990

Copyright: Zuhair Al-Nerabieah©2021. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Tumor Thickness (TT) plays an important role in the progress and prognosis of malignant tumors in general

and oral squamous cell carcinoma in particular. Many studies have concluded that thicker tumors were associated with higher

incidence of regional lymph node metastasis and as a result were associated with more lower survival rates.

Aim of Study: This study aimed to evaluate relation between tumor thickness (TT) and regional lymph node metastasis in

oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma patients, and to evaluate (TT) as a prognostic factor for lymph node metastasis and as

an influencer in the suggested treatment plan.

Materials and Methods: The study sample contained 40 patients (23 male, 17 female), who were diagnosed with stage I/II

oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. A surgical procedure for tumor excision and an excisional biopsy was performed. The

tumor thickness was measured by one pathologist and the regional lymph nodes status was evaluated pathologically or radiologically

or by the two methods. The study sample was divided into three groups according to tumor thickness: TT<3mm, TT

(3-6mm), and TT>6mm, and the incidence of regional node metastasis in the three studied thickness groups was calculated.

Tumor thickness values were compared in cases of positive regional lymph node involvement and negative regional node

involvement using t-test.

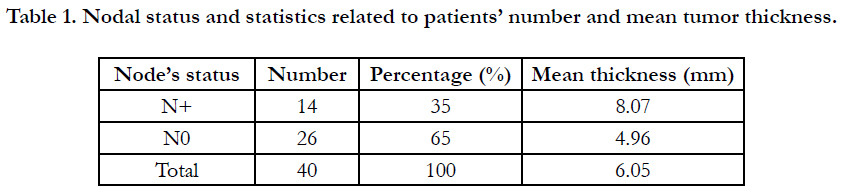

Results: Regional lymph node metastasis had occurred in 14 patients of our whole sample (35%) and the rates of nodal involvement

in the groups of thickness <3mm, 3-6mm, and >6mm were 18.18%, 33.33%, and 47.05% respectively. The mean

tumor thickness was 8.07mm in the positive lymph nodes group and 4.96 mm in the negative lymph node group with statistically

significant difference at p-value<0.05.

Conclusion: There was a higher incidence of regional lymph node metastasis in patients with thicker oral tongue SCC tumors,

also there was a critical high incidence of nodal involvement in OTSCC tumors that exceeded 3mm thick. Prophylactic neck

dissection or irradiation and close monitoring should be considered for those patients with more than 3mm thick tongue

tumors.

2.Introduction

3.Materials and Methods

3.Results

4.Discussion

5.Conclusion

5.References

Keywords

Oral Tongue Cancer; Lymph Node Metastasis; Tumor Thickness.

Introduction

The majority of oral cavity cancers affects the lower parts of

mouth and especially tongue margins and the neighboring floor

of mouth extending backwards to oropharynx. Oral tongue squamous

cell carcinoma (OTSCC) is one of the most common types

of oral cancers. It represents 25- 50% of oral cavity cancers and

includes only the lesions of the anterior tow thirds of tongue. [1,

2].

Tongue SCC (TSCC) is considered one of the most aggressive

types of OSCC. It tends to develop regional lymph node metastasis

earlier and with more incidence compared with the most

other kinds of OSCC,[3-6] also it has in its early stages the larger

mortality rates among various kinds of OSCC. [7]

TNM classification system for tumors staging has been founded

on for many decades. It has formed the reference for clinicians

and pathologists in determining the disease stage and prognosis

and has provided the standard guidelines for tumors treatment.

[8] Clinical practice has demonstrated some deficiency in this classification.

There were many failure cases that were encountered

when the suggested TNM treatment plan was applied, in addition

to that there were some N0 cases of OSCC which did not

respond -as expected- to the standard treatment plan determined

according to this classification. This opinion was supported by

many clinical studies which have confirmed the TNM classification

deficiency in predicting cervical node metastasis, disease recurrence

and survival. [9-15] and have concluded the presence

of many other prognostic factors - other than tumor size - that

influence the disease progression and prognosis such as tumor

thickness (TT) or depth of invasion (DOI), tumor differentiation

grade, perineural invasion, and many other factors.[16-20]

Many recent studies have confirmed on the role of tumor thickness

or depth of invasion in predicting OSCC regional lymph

node metastasis [21-24]. According to these studies the increase

in tumor thickness is associated with higher incidence of regional

lymph node metastasis. The minute knowledge of the role of tumor

thickness in predicting nodal metastasis in TSCC patients

could be resulted in much more control of the disease and as a

result much more survival for those patients by revising the TNM

suggested treatment plan which could be included in some cases

more additional prophylactic procedures and a modified followup

regime, so that in cases of large thickness TSCC tumors the

treatment plan may include an elective neck dissection or irradiation

or at least more close follow-up procedures.[10, 25]

The relation between tumor thickness and nodal metastasis in

OSCC patients has been explored in many studies. [21, 23, 24]

Concerning tongue SCC, most of this studies have evaluated

tongue SCC as a part of a sample population based on OSCC

patients, and few studies evaluated tongue SCC in particular, so

that the relation between tumor thickness and nodal involvement

in TSCC patients still need more studying as every subtype of

OSCC has its specific characteristics related to tumor nature,

clinical behavior, and disease development and prognosis. This

aforementioned reason makes the studying of each subtype of

OSCC separately an issue of great importance.[20, 25]

Materials And Methods

A prospective study was carried out on patients with initial diagnosis

of stage I/II oral tongue SCC who were accepted for

treatment at Al Moasat Hospital - Damascus University – in the

period between 2016 and 2020. Initially all patients suspected to

have Oral Tongue SCC had the routine clinical and radiological

examination for tumor diagnosis and staging.

There were forty patients with OTSCC who had met our inclusion

criteria and were included in our prospective study sample.

All patients included in the study underwent a radiological examination

consisted of plain radiographs, sonography, CT scan and

-when needed- MRI.

All patients underwent a surgical procedure for tumor excision

(partial glossectomy) and an excisional biopsy was obtained and

studied by the same pathology lab. The histological grade and the

maximum tumor thickness were determined by the pathologist

depending on the followed standard histological criteria.

Initially we excluded all patients suffering from recurrent or previously

treated tumors or suffering from tumor metastasis that had

affected the regional nodes or extended beyond it such as patients

with distant organs metastasis or patients with end-stage tumors.

Patients with predictive factors –other than tumor thickness- that

known to influence the incidence of regional lymph nodes metastasis

were also excluded of our sample such as patients with T3,

T4 tumors, patients with histological grade III tumors, and patients

with pathologically confirmed perineural or angiolymphatic

vessels invasion because of the high probability of these types of

tumors to develop regional lymph node metastasis.

On the other hand, all patients with exophytic type tumors and all

cases that had been diagnosed as carcinoma in situ were also excluded

because of the low probability of these tumors to develop

regional lymph node metastasis.

The study sample was divided into two groups depending on the

presence of regional lymph node metastasis:

1-Patients with positive lymph node metastasis (N+).

2-Patients with negative lymph node metastasis (N-).

Also, the study sample was divided into three groups according to

the maximum tumor thickness:

1-Group 1: Patients with tumor thickness <3 mm.

2-Group 2: Patients with tumor thickness 3-6 mm.

3-Group 3: Patients with tumor thickness >6 mm.

Regional lymph nodes status was determined depending on either

neck dissection and consequent pathological study performed on

the surgically obtained nodes specimen or on consequent radiological

and pathological findings obtained during the follow-up

period. The regional lymph nodes were considered positive (N+)

if the pathological result of neck dissection was positive or if

there was a new radiologically or pathologically confirmed lymph

node metastasis that had occurred during the follow- up period.

All patients included in our study were followed–up clinically and

radiologically and when needed histologically for a minimum period

of 16 months. During the follow-up period all patients suffered

from new regional lymph node metastasis were classified in

the positive nodal group (N+), on the other hand all patients who

did not suffer from new regional lymph node metastasis were

classified in the negative nodal group (N-).

When the clinical and radiological and histological examinations

were accomplished the TNM staging was established and the

standard therapy was offered for all study patients which contained

the surgical therapy alone or accompanied by one or more

one kind of treatments (radio or chemo therapy).

Statistical analysis was performed using computed program SPSS

Statistics software (Ver 23: IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). T-test was

used to analyze the difference in tumor thickness values between

the two studied nodal groups, with all statistics were considered

significant at p value<0.05.

Results

40 patients with stage I/II OTSCC were included in our study (23

male, 17 female) with a mean age 65.3 years (range: 42 - 80 years).

All patients underwent a surgical procedure for tumor excision

with or without neck dissection and were followed-up for a mean

period of 28 months (range:16.- 38 months).

The surgical procedure consisted of partial glossectomy, and the

decision of associated neck dissection was taken depending on

patient's clinical and histological findings. Neck dissection was

performed if there was an evident risk of subclinical nodal involvement

such as some large T2 tumors or rapidly growing tumors,

on the other hand when there was no evident risk of nodal

metastasis neck dissection was not performed and nodes status

was determined depending on adjunctive findings obtained during

the follow-up procedures.

According to the size of tumor there were 21 patients with T1

tumor (52.5%), and 19 patients with T2 tumor (48.5%). According

to the histological grade there were 27 cases of grade I tumors

(71%) and 13 cases of grade II tumors (29%).

Regional lymph node metastasis was discovered in 14 patients of

our complete sample (35%), 9 cases (22.5 %) of them were discovered

histologically after elective neck dissection, and 5 cases

(12.5%) were discovered later during the follow-up period.

Tumor Thickness in our whole sample ranged between 1 and 14

mm (mean: 6.05 mm), with a range of (2- 14 mm) in the positive

lymph nodal group (mean: 8.07 mm), and a range of (1 - 11 mm)

in the negative lymph nodal group (mean: 4.96 mm).

The positive lymph nodal group was characterized by higher values

of tumor thickness compared with the negative nodal group

and the difference in TT values was statistically significant (t-test,

p value= 0.006). These results demonstrated that increased tumor

thickness values were associated with more incidence of nodal

involvement in our OTSCC sample.

Table (1) Nodal status and patients' statistics are illustrated in table

1.

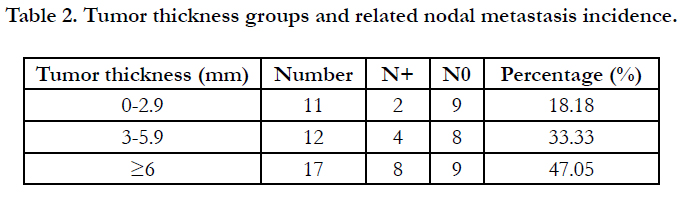

Eleven patients were included in Group 1 of thickness (<3mm),

twelve patients in group 2 (3-6mm), and seventeen patients

in group 3 (>6mm). Two cases of the 11 patients included in

group 1 had regional node metastasis (18.18%), 4 cases in group 2

(33.33%), and 8 cases in group 3 (47.05%). There was a progressive

increase in the incidence of regional nodal metastasis from

the thinner tumors’ groups to the thicker tumors’ groups which

was an expected result because of the aforementioned statistical

relation between regional nodal involvement and the increased

tumor thickness values.

Table (2) Tumor thickness groups and the related nodal metastasis

incidence are illustrated in table 2.

Discussion

TNM tumor classification system depends on tumor size in determining

disease stage and expected prognosis and in establishing

the standard treatment plan. [8, 9] Many recent studies have demonstrated

the presence of other prognostic factors that influence

tumors’ progress in general and oral squamous cell carcinoma in

particular such as tumor thickness or tumor depth of invasion,

tumor’s histological grade, perineural invasion, and many other

risk factors. [21-33]

Tumor thickness is considered an important risk factor for regional

lymph node involvement. [21-24] It may be of superior

influence when compared with tumor maximum dimension as

many recent trials have concluded. [10, 23, 30]

We evaluated in our study the role of tumor thickness (TT) of

oral tongue SCC in the incidence of late regional lymph node

metastasis by analyzing TT values in both studied nodal groups

(positive lymph node metastasis group and negative lymph node

metastasis group) and then statistically comparing the tumor

thickness values in our two nodal groups.

Also, we analyzed the incidence of regional nodal metastasis in

three different ranges of tumor thickness in order to detect the

thickness range that is associated with higher probability to develop

regional lymph node metastasis.

In order to lessen the misdirection in our study we exclude all

cases that is characterized with high or low tendency for nodal

involvement such T3, T4 tumors which were excluded due to the

high probability of these tumors to develop lymph node metastasis, also we exclude the tumors of histological grade III, tumors

with histologically confirmed perineural or Angio vascular invasion

and the recurrent tumors for the same aforementioned reason.

On the other hand, all cases that were diagnosed as carcinoma in

situ or exophytic type cancers were also excluded because of the

low incidence of regional nodes involvement in these kinds of

tumors.

Ultimately our study sample included 40 patients whose neck

were negative in clinical and radiological examination. Tumor

thickness in the positive nodal metastasis group ranged between

2 and 14 mm with a mean thickness of 8.96 mm, and between

1 mm and 11 mm in the negative nodal metastasis group with a

mean thickness of 4.96 mm. TT values were larger in the positive

nodal group with a significant difference as resulted in statistical

study (p value=0.006).

These results conducted with our attempt to exclude the known

risk factors that may affect regional nodal metastasis make us conclude

that thicker tongue tumors have the tendency to develop

regional nodal metastasis more than thinner tumors.

Regional nodal metastasis occurred in 14 patients of our whole

sample (35%). This percentage varies in previous studies on

OTSCC patients for many reasons relating to the inclusion criteria

of each study and the range of thickness values for their included

tumors. In a review of the incidence of late cervical nodal metastasis

in these studies, we find that the rate was 14% in the study

of Kurokawa, 28.88% in Sparano study, 47.7% in Asakage study,

19.3% in Shin study, and 43% in Yuen study. [31-35]

In our study there was a progressive increase in the rate of late

regional nodal involvement from groups of lesser thickness to

groups of larger thickness. In the group of tumor thickness

<3mm there was 18.18% of regional lymph node metastasis, with

this percentage increased to 33.33% in the group of thickness

3-6mm and 47.05% in the group>6mm thick. This increase in the

nodal metastasis incidence was expected because of the aforementioned

statistical relation between regional nodal metastasis

incidence and the increased tumor thickness values in our study

sample.

Yuen et al had recorded 8% of regional nodal metastasis for tumors’

thickness less than 3mm, 44.6% for tumors of thickness

between 3 and 9mm, and 53% for tumors’ thickness >9mm. [35]

The thickness range between 3 and 9mm was here large and needed

an equal distributions of thickness values to reach the real percentage

of metastasis incidence related to this group, because this

percentage is affected directly by the prevalent values of thickness

whether it is high or low values, in other words if high thickness

values are the dominant there will be a bias in results to more

incidence of regional node metastasis in this group, and if low

thickness values are the dominant there will be a bias in results to

less incidence of regional node metastasis in this group.

Shin et al had also studied the influence of tumor’s deep of invasion

in OTSCC patients and had recorded 7.4% of regional nodal

metastasis for tumors DOI of less than 3mm, and 23.2% for tumors

DOI of more than 3mm, [34] also here the group (>3mm)

was of large range of DOI values and again the nodal metastasis

percentage will be affected by the prevalent DOI values of the

group whether it is high or low values.

There was an agreement in previous studies that when occult

nodal involvement exceeds the percentage 20%, then neck therapy

with elective neck dissection or irradiation is indicated. [10, 20,

21] Concerning to tumors of thickness <3mm we have 18.18%

nodal involvement, this rate exceeded the critical value of 20% in

the thickness group of 3-6mm and the group >6mm with nodal

involvement rate 33.33% and 47.05% respectively, and according

to these results elective neck dissection or irradiation should be

considered for tumors of more than 3 mm thick.

Conclusion

Tumor Thickness is a predictor for regional lymph node metastasis

in oral tongue SCC patients. There was a significant incidence

of nodal metastasis in OTSCC tumors of more than 3mm thick

in comparison with tumors of less 3mm thick.

We recommend –within limits of this study- prophylactic neck

dissection or prophylactic neck irradiation and close follow-up

procedures for patients with more than 3mm thick oral tongue

SCC tumors.

Acknowledgment

Damascus University funded this study.

References

-

[1]. Sclar A. Ridge preservation for optimum esthetics and function. The Bio-Col

technique. Postgrad Dent. 1999;6(1):3-11.

[2]. Lekovic V, Camargo PM, Klokkevold PR, Weinlaender M, Kenney EB, Dimitrijevic B, Nedic M. Preservation of alveolar bone in extraction sockets using bioabsorbable membranes. Journal of periodontology. 1998 Sep;69(9):1044-9.Pubmed PMID:9776033.

[3]. Aimetti M, Romano F, Griga FB, Godio L. Clinical and histologic healing of human extraction sockets filled with calcium sulfate. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2009 Oct 1;24(5). PubmedPMID: 19865631.

[4]. Van der Weijden F, Dell'Acqua F, Slot DE. Alveolar bone dimensional changes of post-extraction sockets in humans: a systematic review. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2009 Dec;36(12):1048-58.

[5]. Sclar AG. The Bio-Col Technique. In: Soft Tissue and Esthetic Considerations in Implant Therapy. Carol Stream, IL: Quintessence Publishing Co., 2003:75-112.

[6]. Norton MR, Wilson J. Dental implants placed in extraction sites implanted with bioactive glass: human histology and clinical outcome. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2002 Mar 1;17(2).

[7]. Tonetti, MS, Hammerle, CH. European Workshop on Periodontology Group C. Advances in bone augmentation to enable dental implant placement: Consensus Report of the Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology. Journal of Clinical periodontology., 2008; 35(Suppl): 168–172. PubmedPMID: 18724849.

[8]. Chen, ST,Buser, D. Clinical and esthetic outcomes of implants placed in postextraction sites. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants., 2009 ;24(Suppl): 186–217. PubmedPMID:19885446.

[9]. Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, DohanSL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al.Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): a second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral RadiolEndod., 2006; 101:e37-44. PubmedPMID:16504849.

[10]. Wang HL, Kiyonobu K, Neiva RF. Socket augmentation: rationale and technique. Implant Dentistry. 2004 Dec 1;13(4):286-96.

[11]. Gupta D, Gundannavar G, Chinni DD, Alampalli RV. Ridge Preservation done ImmediatelyfollowingExtraction using Bovine Bone Graft, Collagen Plugand Collagen Membrane. International Journal of Oral Implantology and Clinical Research. 2012 Jan 1;3(1):8-16.

[12]. Sabelman EE. Biology, biotechnology and biocompatibility of collagen. Biocompatibility of tissue analogs. 1985:21-66.

[13]. Postlethwaite AE, Seyer JM, Kang AH. Chemotactic attraction of human fibroblasts to type I, II, and III collagens and collagen-derived peptides. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1978 Feb 1;75(2):871-5. [14]. Sakka S, Coulthard P. Bone quality: a reality for the process of osseointegration. Implant dentistry. 2009 Dec 1;18(6):480-5. Pubmed PMID: 20009601.

[15]. Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): a second-generation platelet concentrate. Part II: platelet-related biologic features. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 2006 Mar 1;101(3):e45-50.

[16]. Inchingolo F, Tatullo M, Marrelli M, Inchingolo AM, Scacco S, Inchingolo AD, et al. Trial with Platelet-Rich Fibrin and Bio-Oss used as grafting materials in the treatment of the severe maxillar bone atrophy: clinical and radiological evaluations. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010 Dec 1;14(12):1075- 84.

[17]. Schwartz-Arad D, Chaushu G. The ways and wherefores of immediate placement of implants into fresh extraction sites: a literature review. Journal of periodontology. 1997 Oct;68(10):915-23.

[18]. Iyer S, Weiss C, Mehta A. Effects of drill speed on heat production and the rate and quality of bone formation in dental implant osteotomies. Part I: Relationship between drill speed and heat production. Int J Prosthodont. 1997; 10:411–414. Pubmed PMID:9495159.

[19]. Iyer S, Weiss C, Mehta A. Effects of drill speed on heat production and the rate and quality of bone formation in dental implant osteotomies. Part II: Relationship between drill speed and healing. Int J Prosthodont., 1997; 10:536–540. Pubmed PMID:9495174.

[20]. Tehemar S. Factors affecting heat generation during implant site preparation: a review of biologic observations and future considerations. Int J Oral MaxillofacImplants., 1999; 14:127–136. Pubmed PMID:10074763.

[21]. Garg AK. The use of osteotomes: a viable alternative to traditional drilling. Dent Implantol Update. 2002; 13:33-40. Pubmed PMID:12060956.

[22]. Saadoun AP, Le Gall MG.Implant site preparation with osteotomes: principles and clinical application. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. Jun-Jul 1996;8(5):453-63.Pubmed PMID:9028267.

[23]. Yin XM, Dai JX, Wang XH, Xu DC, Zhong SZ. Observation of blood supplies system to mandible in transparent specimen. Shanghai kouqiangyixue= Shanghai journal of stomatology. 2003 Aug 1;12(4):266-8.

[24]. Hahn J. Clinical uses of osteotomes. Journal of Oral Implantology. 1999 Jan;25(1):23-9.