An Assessment of Occupational Stress, Job Satisfaction and Coping Strategies among Dentists in Damascus, Syria

Fatima KAlmasri*, Ali Al-sheikh Haidar

Oral Medicine Department, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Damascus, Syria.

*Corresponding Author

Fatima KAlmasria,

Oral Medicine Department, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Damascus, Syria.

Tel: +963969960118

E-mail: fatema.almasri92@gmail.com

Received: October 07, 2020; Accepted: November 06, 2020; Published: November 13, 2020

Citation:Fatima KAlmasri, Ali Al-sheikh Haidar. An Assessment of Occupational Stress, Job Satisfaction and Coping Strategies among Dentists in Damascus, Syria. Int J Dentistry Oral Sci. 2020;7(11):1017-1026. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2377-8075-20000202

Copyright: Fatima KAlmasri©2020. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Dentistry is understood to be a stressful profession.

Aims: (1) To distinguish grounds of stress can help preventing associated adverse effects. (2) To assess the association of various

personal and work related factors with general stress. (3) To evaluate the level of job satisfaction among dentists. (4) To explore

how job satisfaction among dentists is associated with various personal and work related factors. (5) To determine coping strategies

among Syrian dentists.

Methods: Non-randomized and cross-sectional survey had been accomplished between October 2018 to March 2019. The questionnaire

included modified version of the Occupational Stress, developed version of the dentist satisfaction survey. Besides, the

coping strategies were administered for 409 dentists.

Results: With response rate (82.8 %), 61.86% was reported being stressed. The most common cause of stress has maintained

high levels of concentration. Least frequent stressor wasTreatment of patient with maladaptive response to nervous functions.

The mean score of total careers of the respondents was 122.3. There is a medium-strong inverse correlation between scales of Job

stressors and Job satisfaction. Most common coping strategy was referred to the interactions with people.

Conclusions: Dentists are encouraged to implement extensively active coping strategies and participate in stress management

courses helping them in job satisfaction improvement.

2.Introduction

3.Material and Methods

4.Results

5.Discussion

6.Conclusions

7.Refereces

Keywords

Occupational Stress; Job Satisfaction; Coping Strategy; Dentist; Syria.

Introduction

Stress nowadays is a natural and unavoidable part of everyday

lifeand all people need a certain amount of stress, otherwise their

lives would be dull. Stress is responsible each year for the loss of

some 100 million working days; perhaps this is why the topic of

stressful work has attracted the attentions of many researchers

[1]. Seley [2] characterized stress as "the spice of life", although

too much stress may be damaging to body, some stress may be a

source of motivation if put under proper control. The long-term

exposure to stress can be a triggered for many psychosomatic

disorders [3], poor job performance, poor job satisfaction, poor

family, peer and coworker relations, as well as decreased life satisfaction

and general well‑being [4].

In recent years, Occupational stress has become an increasingly

serious problem around the world [5]. It is common within health

care professionals in the developed countries, although less is

known about its prevalence inMiddle Eastern countries [6]. Over

the years, studies have shown that experiencing stress in the work

setting leads to undesirable consequences on the well‑being and

safety of an individual and invariably for the organization [7].

Although dentists occupy an important position in the society,

dentistry has been considered one of the most stressful of all

healthcare professions [3]. The image of dentistry as being stressful

is part of the dental culture and tends to override the personal

experience due to the nature and working conditions as in the

dental surgery [8]. Job-related factors are almost explaining half

of the overall stress in a dentist’s life [9]. Levels of burnout (exhaustion)

are increasing [7], which appears to be related to deficits

in executive functioning or cognitive control [10]. Cross-sectional

studies had indicated that 10% of dentists experience high levels

of burnout [11].

Researchers from the BDA (Business Development Agreement) found high levels of stress and burnout amongst a survey of

more than 2,000 UK dentists where 17.6% admitted that they had

seriously thought about committing suicide [8].

Career satisfaction is a one central indicator of subjective career

success [12]. An American study used the dentist satisfaction survey

(DSS) [13], has investigated external or environmental factors

contributing to a job satisfaction, nonetheless, research involving

individual-level factors is relatively scarce. By focusing on intrapersonal

factors, we can be able to better explain why individuals in

similar work environments experience differing levels of satisfaction.

Cope is the constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts

to manage specific external and/or internal demands that

are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person

[14]. Coping strategies come under two broad classifications:

1- Adaptive: problem‑focused coping, long‑term, as past experience

- talking it out with others, are seen as constructive ways of

dealing with stress, and 2- Maladaptive: emotion‑focused coping

and short‑term as eating, sleeping, smoking, are reducing tension

temporarily, but do not deal directly with the stressful situation

[15]. Coping has been acknowledged as a mediator between encountered

stress and life adjustment outcomes [16].

Only meager number of surveys has been undertaken to assess

stress, satisfaction and cope behaviors of dentists. Thereon, the

current subject aimed to investigate sources of occupationalstress,

job satisfaction and coping strategies among them and then

tracking their relationship with the demographic characteristics

of dentists.

For this purpose, the following test tools were considered with

their reliability, validity and objectivity mentioned in their respective

manuals. The first section of the questionnaire collated-demographic

information, including gender, age, and social status,

specialty, years of experience, working hours per week, income

and number of patients treated per day. The second section consisted

of the modified version of the Occupational StressIndicator

(OSI) questionnaire devised by Cooper et al., [17] was used to

obtain information about job stressors. It consisted of 33 items

within the following seven scales: time pressures, financial stressors, patient-related stressors, staff problems, profession-related

stressors, and the nature of work and Fears from future.The response

options were as follows: ‘never’, ‘seldom’, ‘sometimes’,

‘often’ and ‘all the time’. Similar versions of this questionnaire

have been used widely in dental research [18]. The third section

comprised the DSS [19] instrument with minor modifications

made to reflect cultural uniqueness (i.e. spacing medical insurance

regimens, tradition, convention, education, illiteracy prevalence),

more appropriate for Syrian dentists. It consisted of 37 items:

Seven items to measure the factor of overall professional satisfaction

(OPS) and 30 items related to 10 work environment factors.

The supplementary material (SM) reproduces the DSS. Note

that negatively phrased items were incorporated into the survey

and are underlined in the SM. The work environment factors included:

Perception of staff, Income, Professional relations, Time

management, Stress, Patient relations, Personal time, Prudent

strategies, Respect, and Delivery of care. All items were measured

by a 5-point Likert scale: 1=Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree,

3=Neither Agree nor Disagree, 4=Agree, and 5=Strongly Agree.

The last section consisted 10 strategies, was used for coping with

stress; Fig.S1

The paper has not investigated the correlations between the naturally-

occurring biological diseases (incl. oral) and the occupational

stress.

Inclusion criteria: This cross-sectional study took place between

October 2018 and March 2019 among dentists working in Damascus,

Syria, who had more than two years of work experience.

Exclusion criteria: A participant, who did not graduate from

Syrian university or complete the questionnaire.

Sample size: The sample was non-randomly selected (not randomized),

the questionnaire was posted with a covering letter

explaining the study’s purpose. 409 of dentists were invited to

participate in the study.

The sample size was estimated using G * Power (ver. 3.1.9.2, Universität

Kiel, Kiel, Germany), and the minimum sample size was

calculated for analysis using a chi-squared test. To obtain a 95%

confidence, and at least 5 percent-plus or minus-precision, this

gave Z values of 1.96, per the normal tables. Considering the internal

consistencies, the minimum required sample size for the objective of the study was calculated using the Cochran’s formula

for cross-sectional surveys, as follows:

n = t2P(1-P)/d2 = (1.96)2 × 0.70 × 0.30/(0.05)2 = 322

d: is the desired level of precision (i.e. the margin of error),

P: is the (estimated) proportion of the population which has the attribute in question, and

t: is the effect size that is given in the normal distribution table (z-table).

Therefore, the minimum sample size of surveys was 322 and the

final sample was 339, which fulfilled this statistical requirement.

The survey responses were entered into an electronic database

then the entry errors and outlier values were reviewed. Descriptive

statisticswere expressed as mean )μ), Standard deviation (SD)

andfrequency (ʋ). Further data screening was made to check all

variables for missing data, skewness and kurtosis. A student’s ttest

was used to compare the effects of variables. Associations between

categorical variables were tested for statistical significance

using the Chi-square test (χ2) [20]. P values were determined for

the continuous and categorical variables using the Mann-Whitney

U test and χ2 test, respectively. Cronbach Alpha coefficients of

the factors extracted in the analysis were identified to test the reliability

of the dimensions. The score of items for each factor were averaged to determine the degree of satisfaction. The average

scores of each factor were classified into three categories based

on the mean score in line with previous research [22]: dissatisfied

(1.0–2.5), neutral (>2.5–<3.5), and satisfied (3.5–5.0). (Table S1)

Total career score (TCS) was defined as a total score of all items.

All statistical analyses conducted using SPSS version 24 Independent

t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA), were implemented

to compare variables of demographic and practice characteristics.

Stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to identify predictors

or TCS and its related personal and professional characteristics,

p-values <0.05 were considered as having statistically significant

differences. The fallouts from the logistic regression were

expressed as 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

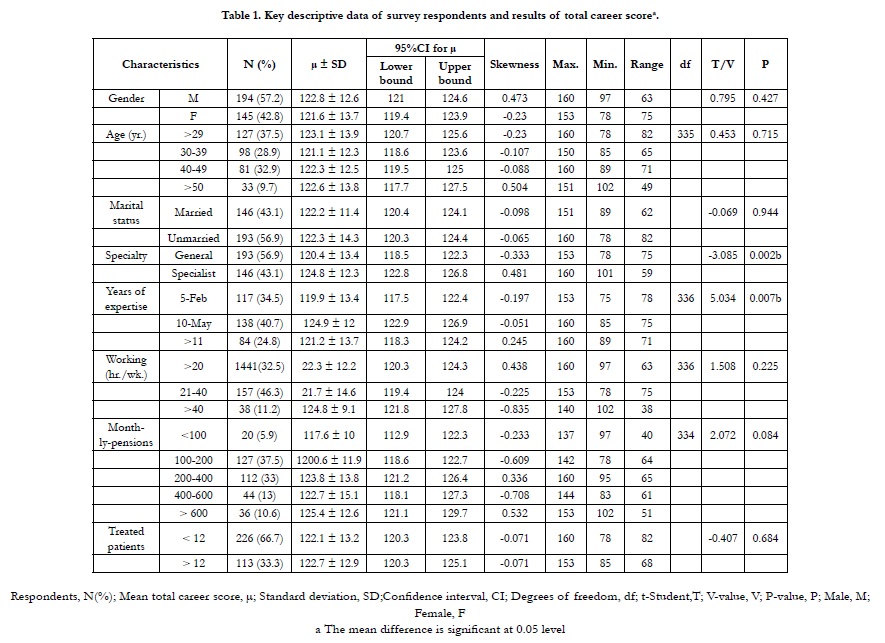

Of the 409 dentists invited to participate in the study, 371 responded

(Males are the majority; Age distribution bands in decrement

sequence: ≤29, 30-39, 40-49, ≥50; Unmarried dentists and

General dentists were 124.4% that of Married and Specialists,

respectively; Years of expertise distribution bands in decrement

sequence: <10, 2–5, 6–10; Working (hr./wk.) bands in decrement

sequence: 21–40, <20, >40; Silent majority of Syrian dentists

monthly-pensions is ranged between $100-400; Preponderance

of treated patients: ʋ (<12); Total response rate (TRR): 82.8%;

Table 1) while 32 participants were excluded.

There was a considerable variation in the number of stressors that dentists experienced frequently or all thetime, with the number per dentistranging from 1 to 28. The frequency with which the various stressors were reported as occurring ‘very often’ or all the time (Table S2).

An Exploratory Factor Analysis method was used to determine the degree of correlation of the stressors in each section, 33 Stressors are summarized into seven sections using the Principal Component method, and variables branched were redistributed to the sections using the method of varimax, and these sections together contributed to explaining 61.05% of the total variance. (Table S3)

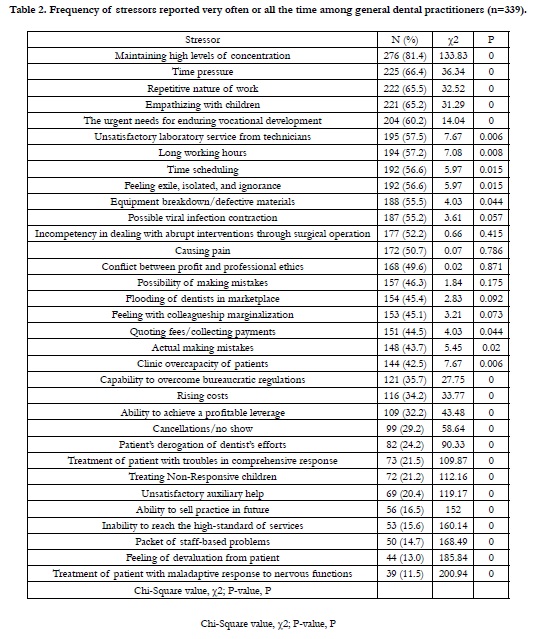

The quality of the factor analysis was significant .Also, using Bartlett's Test, this test is significant (χ 2 = 5974.2, p.value = 0.000 < 0.05) (Table S4). The most commonly reported stressors under the control management standard were Maintaining high levels of concentration, Time pressure (considering work schedule, time of work, and breaking time) and Repetitive nature of work. Work stress caused general stress response syndrome.

The least frequent stressors were Treatment of patient with maladaptive response to nervous functions, Feeling of devaluation from patient, and Packet of staff-based problems. 61.86% reported often being stressed (Table 2 and Table S5).

Table 2. Frequency of stressors reported very often or all the time among general dental practitioners (n=339).

Cronbach Alpha of Vocational stressor, Pressure stressor, Nature of work stressor, Financial stressor, OSI,Future stressor,Patientrelated stressor, Staff stressor are 0.935, 0.887, 0.858, 0.849, 0.712, 0.699, 0.673, 0.649, respectively andinternal consistency reliabilityof OSI (P-value: 0.000; All values were significant for α=0.05).(table S6)

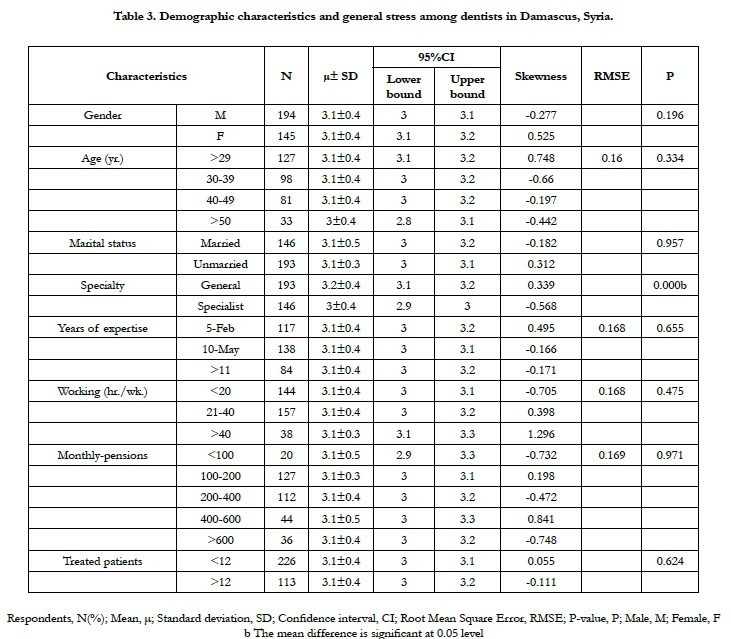

The demographic characteristics of the participants and relationships with general stress are presented in Table 3. There was no significant relationship between general stress scores and gender (men have presented slightly higher job stress which was not significant with females), age, social status,years of experience, working hours per week, income, and number of patients treated per day. However, general stress showed a significant correlation with Specialty (P = 0.000). T-test showed that general dentists exhibited higher stress than specialist dentists, the mean difference was statistically significant (P = 0.00).

Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for DSS is 0.805 and Internal consistency reliability for OPS is 0.8. (Table S7)

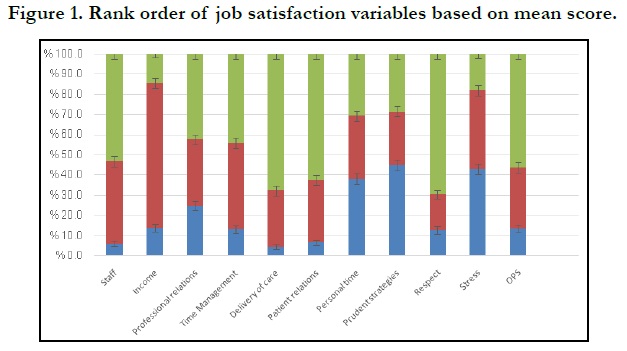

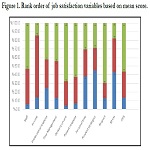

Table S8 depicts the average TCS. The top three highest mean score factors were Delivery of care, Respect, and Patient relations while the three lowest factors were Stress, Prudent strategies, and Personal time. Nearly half of the dentists were generally satisfied. The majority of dentists and staff were satisfied mainly with professional relations but with fair contentment about the income and time assigned for clinic management. The positive engagement in work was accompanied with the improvement in Clinical productivity (No significant association was detected between productivity (Job performance) and job burnout) and so on the dentist’s expenditure. (Table S8. Fig.1)

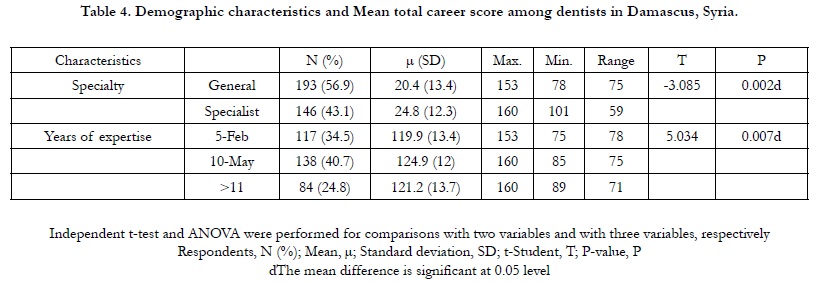

The effect of demographic and practice characteristics on TCS was evaluated by a stepwise-regression analysis (Table 4). Results showed that Specialty and Years of experience were significant predictors of TCS.

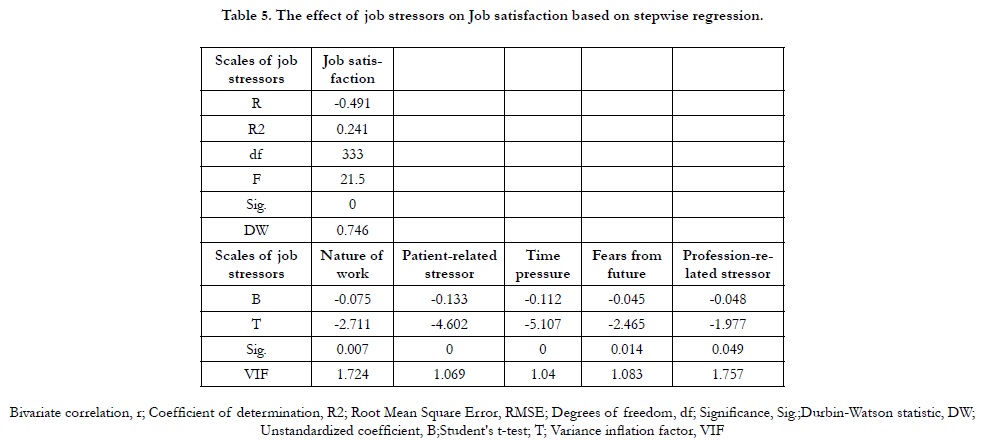

As revealed in Table 5, the ANOVA table shows that the F-statistic was 21.5 and a significance level (Sig.) of 0.000. Therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected and the alternative hypothesis is accepted, proving that there is an impact of job stressors on overall Job satisfaction. In addition, there is a weak inverse correlation between scales of Job stressors and Job satisfaction (Table 5), representing the relative contribution of scales of job stressors (nature of work, patient-related stressors, time pressures, Fears from future, and profession-related stressor) in explaining the variance in the Job satisfaction.( Table S9 shows model summary – testing of hypothesis research).

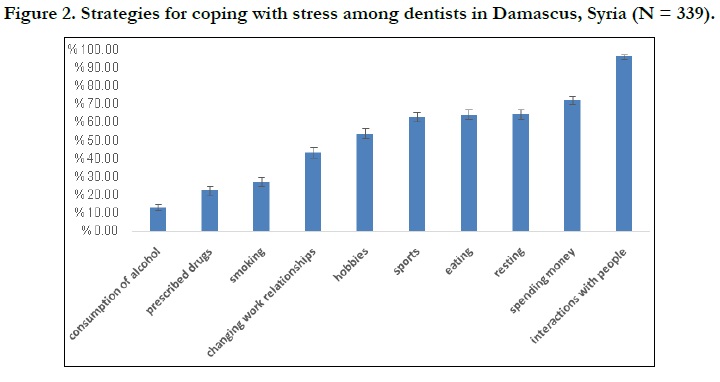

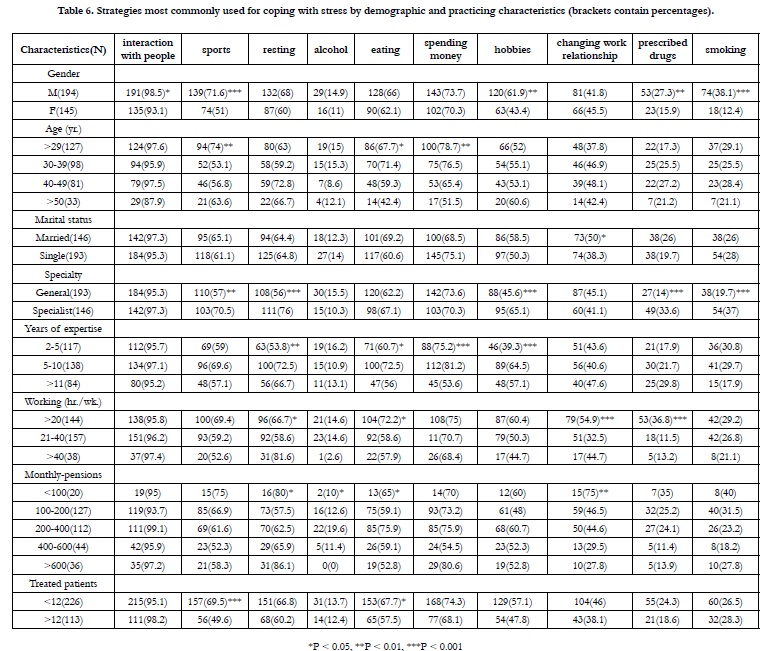

Most common coping strategies used were interactions with people and spending money. The least common strategies were prescribed drugs and consumption of alcohol (Figure 2).

A higher proportion of males and specialists respondents reported using prescribed drugs, playing sports, engaging in hobbies, and smokingto deal with stress. Dentists who had recent graduated were more likely than other age groups to report playing sports and spending money, while older dentists were less likely than other age groups to report eating. Changing the work environment was a strategy used more by married dentists (73, 50%) than unmarried (74, 38.3%). Spending money and eating used as stress-coping strategies by fewer of more experienced dentists. Whereas, engaging in hobbies and resting used by fewer of less experienced dentists to manage stress. More dentists who work > 20 (hr./wk.) reported using drugs, eating, and changing the work environment as strategies for coping with job-related stress, and fewer dentists who have the best Monthly-pensions reported eating, drinking alcohol, and interacting with people as strategies for coping with stress. Whereas dentists who have the highest Monthly- pensions and work >40 (hr. /wk.) reported resting as a strategy to deal with stress. Fewer busier dentists (those who treated, on average, at least 12 patients per day) identified resting, eating, and playing sports as strategies for coping with work stress (Table 6).

Table 6. Strategies most commonly used for coping with stress by demographic and practicing characteristics (brackets contain percentages).

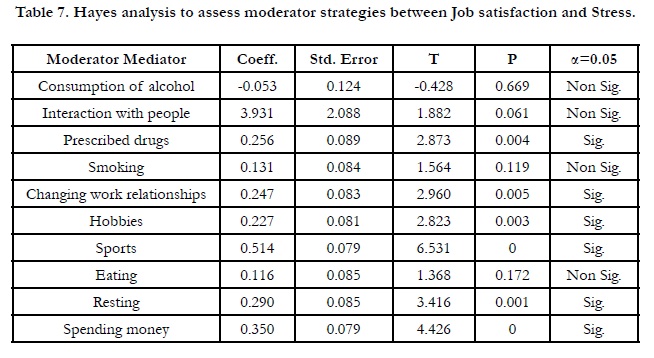

Coping (incl.sports, spending money, resting, prescribed drugs, changing work relationships, and hobbies, respectively) served as a mediator between stress and experienced job satisfaction. With emotion focused coping, feeling loneliness and derogative were significantly correlated with job satisfaction which gave rise to advanced levels of psychological disturbance (Table 7).

Variables perceived stress and non-adaptive strategies to cope in addition to adaptive strategies and mindfulness were positively correlated with each other.

Discussion

Stress has widely documented physical and psychological consequences,

such as anxiety, burnout and the development of cardiovascular

diseases [18]. Although there is a number of more

recent stress measures used in the literature, we chose a modified

version of that used by Cooper et al., [17] to allow comparison

with previous work involving dentists.The current study found

that there was a considerable variation in the number of stressors

that dentists experienced frequently or all the time, with the number per dentist ranging from 1 to 28, This result is consistent

with those reported by dentists in New Zealand, the variation is

ranging from 0 to 31 [9].

61.86% of the dentists surveyed suffered from stress. Similar results

have been reported in studies of general dentists in the UK

(68.4%) [18], dentists in Denmark (59.7%) [21].

MTCS and mean overall professional satisfaction subscale score

were 122.3 out of 185 and 3.46 out of 5, respectively. These findings are parallel to other observations conducted in china, which

were 123.12 out of 190 and 3.28 out of 5 [19], respectively. Also,

in Australia, and Sweden studies [22, 23].

The most common stressors among dentists were related to the

nature of work (e.g., maintaining concentration, repetitive nature

of work, and the need to empathizing with children) that caused

their dissatisfaction with their success in their work under pressure.

Many of the frustrations associated with time pressures were

also evident, possibly due to pressure on dentists to schedule as many appointments as possible with limited time, long working

hours, and satisfaction with time was generally average (neutral)

that included professional interrelationship, overseas relations, official

obligations, transportation, In addition to private interrelations

(time allocated for personal relations and community meetings,

time assigned for research, and other interests not related to

work).

These frustrations may be partly the result of external pressures

to meet certain responsibilities (e.g., pressures by family and

friends, colleagues, and the medical community); but may also in

part be the result of the dentists’ own personal set of values and

sense of responsibilities, and urgent needs for enduring vocational

development, as there is a great emphasis these days on conducting

and publishing research, such circumstances undoubtedly

lead to increased tension, creating difficulties in integrating work

responsibilities with social life.These results are similar to those

in previously reported study [24]. Ayers et al. reported that the

second and third most common sources of stress among general

dentists in New Zealand were time-related pressure (48%) and the

need to maintain high levels of concentration at work (43%) [9].

In a study of dentists in Islamabad, Pakistan, finding enough time

for family and friends was reported as the most common source

of stress [24]. Cooper et al. indicated that time management problemswere

a common source of stress among dentists [17]. Other

study indicated that respondents were dissatisfied with stress and

time management [19].

Dentists in this study also pointed out many aspects of the practice

related to the conditions of the profession in general and

reported that it was stressful and negative for them ( e.g., feeling

with colleagueship marginalization, flooding of dentists in marketplace,

the urgent needs for enduring vocational development ,

fear of making mistakes or actually committing them, incompetency

in dealing with abrupt interventions through surgical operation,

equipment breakdown/defective materials, and unsatisfactory

laboratory service from technicians).

52.2% of respondents experiencing of medical emergency in the

dental surgery [9], although it has been found to be one of the

most highly ranking stressors in the UK [17], only 15% of dentists

reported that this was a stressor very often or all the time [9].

This may reflect a difference in the wording of the questionnaires

used; Cooper et al. [17] used a five point Likert-type scale ranging

from ‘no stress’ to ‘a great deal of stress’, whereas we used

a similar scale labeled ‘never’ to ‘all the time’. Although a medical

emergency would be one of the greatest potential sources of

stress, it does not occur commonly, and many dentists may not

have experienced such an event. Dentists also reported low satisfaction

with professional relationships, such as their relationships

with specialists in the medical arena and their contact with global

expertise.

Pressure related to income is clearly visible in dentists' self-reports

at work. Dentists have struggled with a conflict between profit

and professional ethics due to the increase in the general costs of

running a dental clinic and the necessity to pay specific fees, so

they need to work harder and see more patients and working long

hours to generate sufficient income.Income-related stressors are

reported to behigh for dentists working in the National Health

Service [25], where there is a perceived need to work quickly inorder

to generate sufficient income.

Job satisfaction with financial condition was low which included

pension, overall expenditures, conciliating paid-salaries and allowances,

billings, and premium-insurance payment.It seems that

negative attitudes about the health care system were predicted by

dissatisfactions and frustrations with procedures, limitations, and

bureaucratic regulations imposed on the profession by the government,

these pressures were less than previously reported [26].

The least frequent stressors were patient-related stressors (e.g.,

treatment of patient with troubles in comprehensive response,

treating non-responsive children, and feeling of devaluation from

patient).Ayers et al. [9] reported the most common source of

stress was treating uncooperative children (52%), and Kay et al.

reported that the most common stress is the patient’s demands

(75%), in the UK involved treating difficult or uncooperative

patients (64.8%) [27]. Dentists were satisfied with their patient

relations, as many dentists enter into medical school with noble

ideas of helping those who are suffering and in pain, and that

helping patients and being able to treat illness during patients’ adherence

to medication regimen were aspects of medical practice

that dentists valued and found meaningful. It is possible that the

gratification of knowing that someone in need has been helped is

one factor that makes the long hours and heavy workloads of the

dentist’s job more manageable.

Dentists appeared that the least sources of stress are the problems

of staff, majority of dentists were highly satisfied with performance

of the medical assistants, teamwork in healthcare, team

involvement in troubleshooting, this is due that staff was hired

and managed by the dentist or the organization affiliated with it.

Kay et al. reported that problems associated with staff are the

most common (56%) [27]. It is evident that the work of a dentist

still provides a great deal of general satisfaction as a career choice.

Respondents were neutral in their satisfaction with the practice

of the profession (dentistry fulfills current career aspirations,

satisfaction in work, ability dealing with disabilities, continuous

desire to gain knowledge, unwillingness to change career, and urging

high-school students to study dentistry), possibly it relates to

wanting to move away from any health-related job, having been

dissatisfied with one health-related career, it may also be that these

alternatives are more financially rewarding with less stress.

A number of stressors contributed significantly to dissatisfaction

with work as a dentist, the same stressors that contributed

to overall stress also contributed to dissatisfaction with practice.

It is difficult to speculate on the causal relationship between the

concepts of satisfaction and stress, the results show a negative

significant correlation between stress and job satisfaction.

Therefore, improving work condition is essential in order to

increase the level of satisfaction and thus to lower the level of

stress. Similar results were obtained in other professions [19].

No significant differences in occupational stress were observed

betweenmales and females, this finding mirrored two studiesin

Yemen and Iran which reported nostatistical differencesin stress

among men and women. However, Rogers et al.reported that

female Irish dentists were morestressed than males [20]. It was

found that males suffer from pressures related to the nature of

work more than females, one study showed males suffer from maintaining high levels of concentration and causing pain more

than females [9], perhaps because of childrearing and familyresponsibilities

greatly impact females’ working life and thatfemale

dentists are more likely to take a career break by more personal

time and relatively long maternity leave. While, female dentists

have suffered from financial and patient-related pressures more

than male, due to mismatch between the number of patients

treated and personal obligations.

The results reveal no gender differences in satisfaction levels, this

result is consistent with previous observation [15], and contrast

with two studies from Australia which referred to that female dentists

had higher job satisfaction than male dentists [22, 25]. Other

study conducted in Turkey reported that male dentists had higher

mean career satisfaction scores than female dentists [28].

Additionally, there were no significant differences in general stress

according to age, and this is consistent with a study reporting no

relationship between stress and age [24]. Older dentists were less

concerned about patient pressures, this is due to they are often

more experienced, which increases the ability to treat patients

with weak response, in addition to our society's traditions of respecting

and appreciating older dentists.Contrary to our findings,

there is no statistically significant difference in satisfaction according

to age; several previous studies indicated that older dentists

were more satisfied or less depressed with dentistry [15, 25].

There were no statistically significant differences in general stress

according to the working hours per week. More working hours

caused time pressures and more patients to secure sufficient income,

and increased fears of future. Ayers et al., reported that

time pressures and long work hours had a significant impact on

the stress of the dentist, and stated that weekly workload increased

fears related to future [9]. General satisfaction was not

associated with hours worked per week, but Chinese study, dentists

who work less than 40 hours per week were generally more

satisfied with dentistry [19].

According to years of experience, there were no statistically significant

differences in general stress, compared to study in Iran

that found dentists with fewer than 10 yrs. of experience exhibited

higher stress than dentists with over 20 yrs. of experience.

Similarly indicated in previous studies reported that experience is

a factor in controlling and managing stress [17, 24].

More satisfaction with dentists had 5-10 yrs. (vs. 2-5 yrs.); this can

be attributed to the decrease in practical and clinical experience,

and the increased fear of making mistakes in the younger dentists.

Overall occupational satisfaction in a study was significantly different

based on years of practice, it was reported that dentists

practicing > 5 yrs. were the most satisfied overall [19], with the

lowest satisfied for dentists with 6-10 yrs., this decrease may result

from increased professional responsibilities in both management

and research and patient care.

There were no statistically significant differences in general stress

and job satisfaction according to the number of patients who were

treated per day. In another study, it was found that longer working

hours also meansless personal time and less freedom of a working

schedule,contributing to lower job satisfaction [27]. There was an

increase in profession-related stressors (e.g.,fear of committing

mistakes or actually committing), in contrast, an increase in fear of the future whit more patients, was attributed to more consumption

of equipment and the possibility of increasing defects.

Specialistdentists were generally more satisfied with dentistry and

less stress than general dentists. They had significantly lower degrees

of time pressure, work pressures, financial pressures, patient

pressures, and fears of future than general dentists. This would

strongly suggest that, in order to improve job satisfaction, practitioners

should define their preferred fields of dentistry, and strive

to gain more experience and training, while avoiding areas where

they have less interest or ability.

There were no significant differences in overall stress and satisfaction

according to income. While there is an increase in professionrelated

stressors, the lower the monthly income, the reason may

be that dentists resort to using less quality materials or because of

their inability to equip their patients with modern equipment that

helps them in continuing professional development because of

the high prices that contradict their low income.

The most common techniques for managing stress identified

in the current study were interactions with people (92.2%); this

strategy did not modify the relationship between satisfaction and

stress, it is likely that dentists interact with people more, without

identifying this as a technique to manage stress, spending

money (72.3%) and resting (64.6%). The least commonly used

were smoking (27.1%), prescribed drugs (22.4%) and alcohol

consumption (13.3%). In New Zealand, the most common reference

strategy was interactions with people (77.3%), while the least

strategies were smoking (4%) and prescribed drugs (3%) [9].

Tobacco use as a coping mechanism is similarly low in the UK

8.6% and in Iran 4.3% of dentists reporting that they smoke to

manage stress [17, 27] Similarly, smoking and drug use were not

frequently reported as strategies used by Dutch dentists to manage

stress [29].

13.3% of the respondents used alcohol to relieve stress, other

authors have reported worrying use of alcohol by dentists [29].

Conversely,Myers and Myers [18] reported that, although .90%

of dentists in their sample consumed alcohol regularly, the mean

weekly consumption was low.

Consistent with reports from previous study [30], dentists tended

not to apply active coping strategies forstress management. The

gender differences were not unexpected with males more likely

to report using sports, interacting with people, practicing hobbies,

using drugs and smoking, have been reported as strategies

to relieve stress.There were no statistically significant differences

between males and females regarding the use of the strategy to

change the work environment, and it contradicts a study that

found that more males (26%) use it compared to females (16%).

The strategies used by dentists were similar regardless of their

monthly income, except that a smaller percentage of dentists with

higher income ate and changed the work environment, and none

of them recorded drinking alcohol.

Conclusion

A major cause of stress among dentists is a lack of knowledge

about managing stress [27], the most common type of stress in dentists in Syria has been maintaining high levels of concentration,

time pressure, repetitive nature of work, and empathizing

with children, there are differences in the strategies used by male

and female practitioners to manage stress.

For Syrian dentists, total career satisfaction was judged to be good

overall. Delivery of care, patientand staff relations, and respect

were most satisfied factors, while lack of personal time, lower income,

and stress were the least satisfied factors. A clear increase

in job satisfaction scores was predicted on the basis of specialty

(more specialist) and years of practice 5-10 (vs. 2-5).

Therefore, Policies defining the standard of dental care need to be

made, stress management and coping strategies should therefore

be included in the dental curriculum in order to avoid physical

and psychological problems that may occur later as a result of

occupational stress, and workshops, seminars and education programs

on occupational stress and practice management for dental

students and dentists should be organized periodically.

Stress literature is curious, particularly given its importance in the

depression literature.

Further exploration of the importance of this variable may therefore

remain a good avenue for further research.

Future studies exploring the job satisfaction of Syrian dentistscan

build upon this study byother regions with different demographicsand

investigating how leadership roles impact job satisfaction,

to identify interventions that can be used to reduce stress between

dentists and improve their working conditions.

References

- Johnson PR, Indvik J. Stress and workplace violence: it takes two to tango. J ManagPsychol. 1996 Sep 1;11(6):18-27.

- Selye H. Stress without Distress. In: Serban G. (eds) Psychopathology of Human Adaptation. Springer, Boston, MA, pp.137-146, 1976.

- Gangwar A, Kiran UV. Occupational Stress among Dentists.J Sci Eng Res. 2016;4(7):28-30.

- Donald I, Taylor P, Johnson S, Cooper C, Cartwright S, Robertson S. Work environments, stress, and productivity: An examination using ASSET. Int J Stress Manag. 2005 Nov;12(4):409.

- Islam MM, Ekuni D, Yoneda T, Yokoi A, Morita M. Influence of Occupational Stress and Coping Style on Periodontitis among Japanese Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Sep 22;16(19):3540.Pubmed PMID: 31546684.

- Boran A, Shawaheen M, Khader Y, Amarin Z, Hill Rice V. Work-related stress among health professionals in northern Jordan. Occup Med (Lond). 2012 Mar;62(2):145-7.Pubmed PMID: 22121245.

- Denton DA, Newton JT, Bower EJ. Occupational burnout and work engagement: a national survey of dentists in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J. 2008 Oct 11;205(7):E13.Pubmed PMID: 18849939.

- Collin V, Toon M, O'Selmo E, Reynolds L, Whitehead P. A survey of stress, burnout and well-being in UK dentists. Br Dent J. 2019 Jan 11;226(1):40- 49.Pubmed PMID: 30631165.

- Ayers KM, Thomson WM, Newton JT, Rich AM. Job stressors of New Zealand dentists and their coping strategies. Occup Med (Lond). 2008 Jun;58(4):275-81.Pubmed PMID: 18296684.

- Chipchase SY, Chapman HR, Bretherton R. A study to explore if dentists' anxiety affects their clinical decision-making. Br. Dent. J. 2017 Feb;222(4):277-90.

- Gorter RC, Albrecht G, Hoogstraten J, Eijkman MAJ. Professional burnout among Dutch dentists. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1999;27(2):109-116.

- Hall DT, Chandler DE. Psychological success: When the career is acalling. J Organ Behav 2005;26(2):155-176.

- Shugars DA, DiMatteo MR, Hays RD, Cretin S, Johnson JD. Professional satisfaction among California general dentists. J Dent Educ. 1990 Nov;54(11):661-9.Pubmed PMID: 2229622.

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen RJ. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986 May;50(5):992-1003.Pubmed PMID: 3712234.

- Gilmour J, Stewardson DA, Shugars DA, Burke FJ. An assessment of career satisfaction among a group of general dental practitioners in Staffordshire. Br Dent J. 2005 Jun 11;198(11):701-4.Pubmed PMID: 15951785.

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Positive affect and the other side of coping. Am Psychol. 2000 Jun;55(6):647-54.Pubmed PMID: 10892207.

- Cooper CL, Watts J, Kelly M. Job satisfaction, mental health, and job stressors among general dental practitioners in the UK. Br Dent J. 1987 Jan 24;162(2):77-81.Pubmed PMID: 3468971.

- Myers HL, Myers LB. 'It's difficult being a dentist': stress and health in the general dental practitioner. Br Dent J. 2004 Jul 24;197(2):89-93.Pubmed PMID: 15272347.

- Cui X, Dunning DG, An N. Satisfaction among early and mid-career dentists in a metropolitan dental hospital in China. J Healthc Leadersh. 2017 Jun 6;9:35-45.Pubmed PMID: 29355243.

- Roth SF, Heo G, Varnhagen C, Glover KE, Major PW. Job satisfaction among Canadian orthodontists. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003 Jun;123(6):695-700.Pubmed PMID: 12806353.

- Moore R, Brødsgaard I. Dentists' perceived stress and its relation to perceptions about anxious patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001 Feb;29(1):73-80.Pubmed PMID: 11153566.

- Luzzi L, Spencer AJ. Job satisfaction of the oral health labour force in Australia. Aust Dent J. 2011 Mar;56(1):23-32.Pubmed PMID: 21332737.

- Ordell S, Söderfeldt B, Hjalmers K, Berthelsen H, Bergström K. Organization and overall job satisfaction among publicly employed, salaried dentists in Sweden and Denmark. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013 Nov;71(6):1443-52. Pubmed PMID: 23972204.

- Alvi H. The prevalence of stress and associated factors in dentists working at Islamic International Dental College Hospital, Islamabad. Pak Oral Dent J. 2010 Dec 1;30(2):521-5.

- Luzzi L, Spencer AJ, Jones K, Teusner D. Job satisfaction of registered dental practitioners. Aust Dent J. 2005 Sep;50(3):179-85. Pubmed PMID: 16238216.

- Humphris GM, Cooper CL. New stressors for GDPs in the past ten years: a qualitative study. Br Dent J. 1998 Oct 24;185(8):404-6.Pubmed PMID: 9828501.

- Pouradeli S, Shahravan A, Eskandarizdeh A, Rafie F, Hashemipour MA. Occupational Stress and Coping Behaviours Among Dentists in Kerman, Iran. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2016 Aug;16(3):e341-6.Pubmed PMID: 27606115.

- Sur H, Hayran O, Mumcu G, Soylemez D, Atli H, Yildirim C. Factors affecting dental job satisfaction: a cross-sectional survey in Turkey. Eval Health Prof. 2004 Jun;27(2):152-64.Pubmed PMID: 15140292.

- Gorter RC, Eijkman MA, Hoogstraten J. Burnout and health among Dutch dentists. Eur J Oral Sci. 2000 Aug;108(4):261-7.Pubmed PMID: 10946759.

- Newton JT, Gibbons DE. Stress in dental practice: a qualitative comparison of dentists working within the NHS and those working within an independent capitation scheme. Br Dent J. 1996 May 11;180(9):329-34.Pubmed PMID: 8664089.