Association Of Age, Gender and Teeth Distribution in Patients Undergoing Class I Metal Inlay Restoration

Sahil Choudhari1, S Haripriya2*, Jaiganesh Ramamurthy3

1 Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai, India.

2 Senior Lecturer, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai, 600077, India.

3 Professor and Head, Department of Periodontics, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai, 600077, India.

*Corresponding Author

S Haripriya,

Senior Lecturer, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha

University, Chennai, 600077, India.

E-mail: haripriyas.sdc@saveetha.com

Received: September 06, 2020; Accepted: October 09, 2020; Published: October 27, 2020

Citation:Sahil Choudhari, S Haripriya, Jaiganesh Ramamurthy. Association Of Age, Gender and Teeth Distribution in Patients Undergoing Class I Metal Inlay Restoration. Int J Dentistry Oral Sci. 2020;7(10):946-950. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2377-8075-20000187

Copyright: S Haripriya©2020. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Inlay is an indirect restorative technique which is a conservative approach to prevent full coverage restorations. Inlays can be

fabricated by using metal, composite or ceramics. The aim of the study was to find the association between age, gender and tooth

number in patients undergoing class I metal inlay restoration. Samples were collected from June 2019 - March 2020. It included all

the people who had undergone class I metal inlay restoration. A total of 37 class I metal inlay procedures were done. The collected

data was tabulated using microsoft excel and analysed using SPSS. Incomplete data was excluded from the study. Statistical analysis

was done using a chi-square test. In our study, we observed that the age group below 30 years, reported the most for class I metal

inlay restoration with higher incidence of males. Tooth 37 was the most common tooth involved in class I metal inlay restoration.

Association between gender and class I metal inlay restorations revealed that the highest number of class I metal inlay restorations

were done in males in tooth number 37, and the least were done in females in tooth number 38(p >0.05), however it was not

statistically significant. Association between age and class I metal inlay restorations revealed that patients in the age group above

30 years underwent higher number of class I metal inlays in tooth number 37 and the least being patients in the age group above

30 yrs involving tooth number 36 (p >0.05), however it was not statistically significant.

2.Introduction

3.Materials and Method

4.Results and Discussion

5.Conclusion

6.Acknowledgement

7.References

Keywords

Inlay; Ceramics; Composite; Metal.

Introduction

Dental caries in permanent teeth is highly prevalent, affecting

about 35% of the world population especially in posterior teeth

[1]. Dental caries is the most common cause for the loss of tooth

structure in a clinical situation [2]. Although caries is the predominant

reason for loss of tooth structure, several other non-carious

lesions, such as erosion, abfraction, attrition and fracture may also

lead to breakdown of the hard tissues of the teeth, necessitating

their restoration [3, 4].

There are several different options to perform posterior restorations,

including direct materials (amalgam, composite) and indirect

materials (composite, ceramic, metal). The selection, by the

clinician, for a particular material and technique to restore posterior

teeth may be influenced by the dentist’s personal preferences

and skills, patient requests and financial resources, and country

policies, among others [5-8].

Over the past few decades there have been many changes in the

practice of dentistry. In the field of operative dentistry, developments

in the dental material science, together with an increasing

awareness of the need to preserve tooth tissue, have radically altered

the approach to treatment. Many techniques that were considered

standard practice 20 years ago are now rarely used. One

such example is the intracoronal, cast metal inlay restoration. With

the emergence of improved, alternative materials in the form of

composite resins and glass-ionomer cements, use of the simple

cast restoration appears to have declined in recent years [9].

All metal extra-coronal restorations include crowns, onlays. Metal

inlays initially introduced in the USA became widely used in Japan

with the lost-wax technique [10]. Gold alloys were considered the

preferred material for metal inlays because their softness permitted

good marginal sealing and stability. But the high price of gold

alloys was a problem. To achieve both superior properties and

cost effectiveness, silver-based alloys were developed as alternatives

to gold ones [11].

Cast metal offers excellent service and has a long clinical track record.

High noble alloys are desirable for patients concerned with

allergy or sensitivity to other restorative materials. These restorations

can be designed to strengthen the tooth and to conserve

more tooth structure than a full crown. Lower esthetic value is the

probable disadvantage [12].

Conventional intracoronal cast restorations could be improved

by bonding etched metal to enamel. Conventional intracoronal

restorations rely on frictional retention of the casting by opposing

walls of the cavity preparation. This retention is increased by

the adaptation of luting material to surface irregularities whereas,

etched-metal restorations rely on microscopic interlocking of the

resin in the enamel and metal surfaces [13].

Previously our team had conducted numerous in-vitro studies, [14,

15] clinical studies [16-20], reviews [21-25], and surveys [26, 27] in

the last five years. Now, we are focussing on retrospective studies.

The aim of the study was to find the association between age,

gender and tooth number in patients undergoing class I metal

inlay restoration.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at Saveetha Dental College between

June 2019 to March 2020. 86000 patient records were analyzed. A

total of 37 patients who had undergone class 1 metal inlay procedures

were reviewed and analyzed. The data was cross verified

by another examiner to avoid errors. Cross verification of data

was done using photographs and RVGs. Sampling bias was minimised

by verifying the photographs and radiographs by an external

reviewer. After verification of dental hospital management

system records of all patients, data such as name, age, gender and

tooth number of patients undergoing class I metal inlay restoration

were tabulated in Microsoft Excel. Incomplete data and

radiographs which were not of adequate diagnostic accuracy were

excluded from the study. The statistical analysis was done using

SPSS software (SPSS version 21.0, SPSS, Chicago II, USA). The

data was analyzed using a chi-square test. The p value less than

0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.Ethical clearance

was obtained. Ethical approval number SDC/SIHEC/2020/DIASDATA/

0619-0320.

Results and Discussion

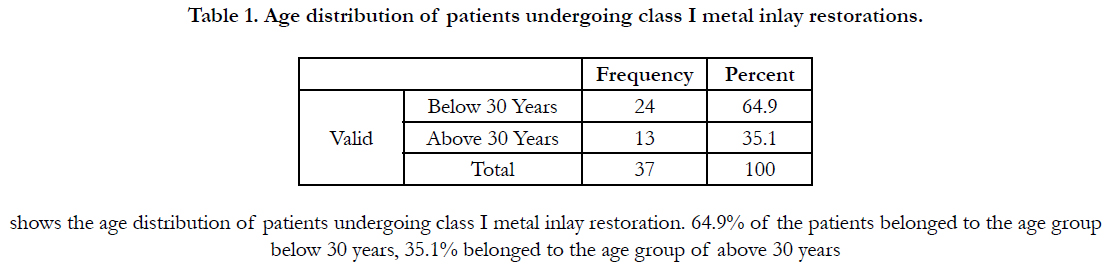

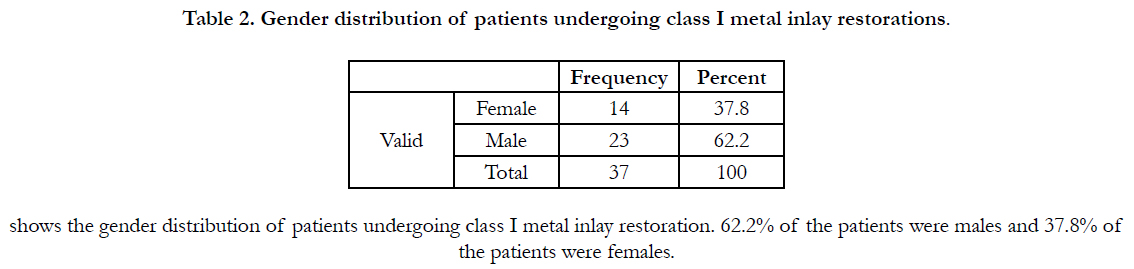

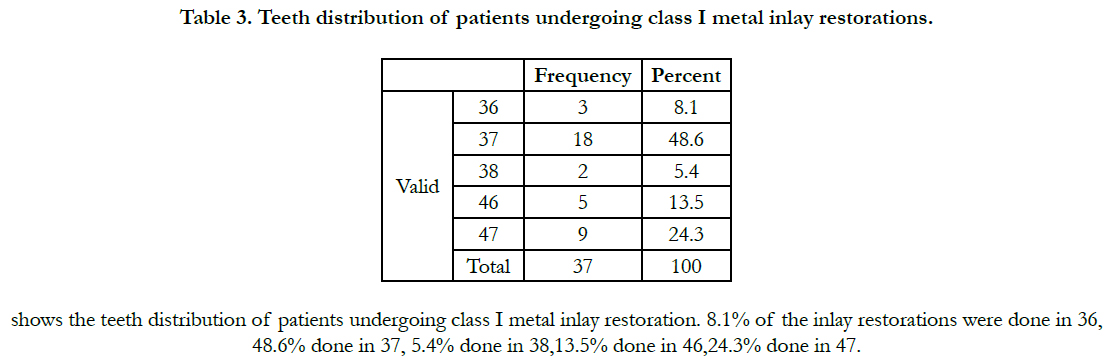

From our study it was observed that among the patients who

had class I metal inlay 64.9% of the patients belonged to the age

group below 30 years (Table 1), 62.2% of the patients were males

(Table 2) and 48.6% of class I metal inlay restoration was done

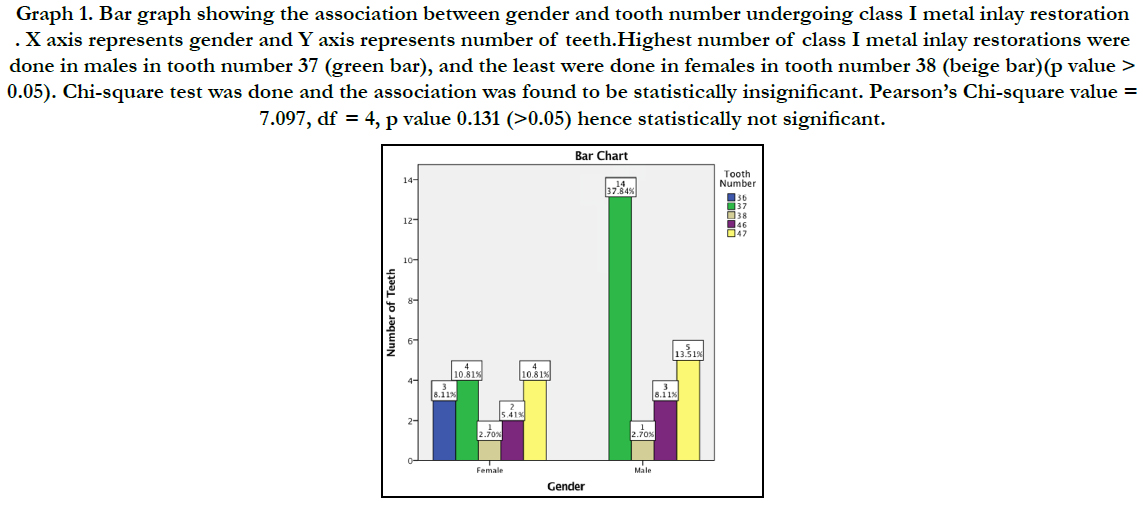

in 37 (Table 3). Association between gender and class I metal inlay

restorations revealed that the highest number of class I metal

inlay restorations were done in males in tooth number 37, and

the least were done in females in tooth number 38 (p value >

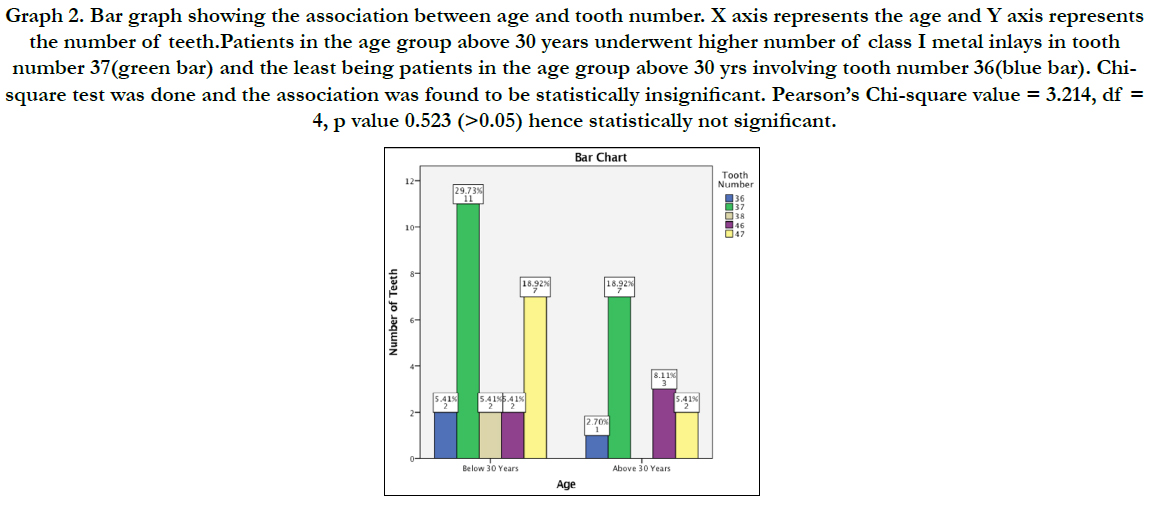

0.05) (Figure 1).Association between age and class I metal inlay

restorations revealed that patients in the age group above 30 years

underwent higher number of class I metal inlays in tooth number

37 and the least being patients in the age group above 30 yrs involving

tooth number 36 (p >0.05) (Figure 2).

Graph 1. Bar graph showing the association between gender and tooth number undergoing class I metal inlay restoration . X axis represents gender and Y axis represents number of teeth.Highest number of class I metal inlay restorations were done in males in tooth number 37 (green bar), and the least were done in females in tooth number 38 (beige bar)(p value > 0.05). Chi-square test was done and the association was found to be statistically insignificant. Pearson’s Chi-square value = 7.097, df = 4, p value 0.131 (>0.05) hence statistically not significant.

Graph 2. Bar graph showing the association between age and tooth number. X axis represents the age and Y axis represents the number of teeth.Patients in the age group above 30 years underwent higher number of class I metal inlays in tooth number 37(green bar) and the least being patients in the age group above 30 yrs involving tooth number 36(blue bar). Chisquare test was done and the association was found to be statistically insignificant. Pearson’s Chi-square value = 3.214, df = 4, p value 0.523 (>0.05) hence statistically not significant.

In a systematic review by Angeletaki et al [28], on indirect restorations no statistical significance in the risk failure between direct versus indirect inlays, after 5 years of function, although results turned slightly in favor of indirect (p = 0.52).In a study done by Olsson et al, [29] women were somewhat more likely to select an indirect restoration compared to men. This is in conflict with our study and a previously reported gender-equal distribution in the utilization of dental care [30].

The higher mean age for individuals choosing an indirect coronal restoration may be related to differences in dental status between age groups. On group level, older individuals have a higher number of missing teeth as well as filled teeth with more missing or filled surfaces [31]. In general, older individuals may thus be more likely to need a crown compared to younger individuals with less burden of caries and with more remaining tooth substance which was contrary to our study in which age group below 30 years reported the maximum for inlay restoration.

Nuckles et al., [32] stated that the cast metal inlay is no longer a reasonable consideration in the conservative treatment of teeth. However, a recent clinical study [33] comparing cast metal inlays with amalgams found inlays to be of higher quality, particularly with respect to marginal integrity. In a study conducted by Sanduet, [34] it was demonstrated stresses are higher in the cast metal restorations and therefore the strength of the teeth is not affected. A taper between 0 and 10 degrees of the preparation is not decisive for the stress values.

Regarding postoperative sensitivity, Cetin et al, [35] reported sensitivity to 4% of the restorations (three indirect, one direct). However, only one indirect inlay required canal treatment and replacement after two years. Similarly, Pallesen and Qvist [36] found 7% and 10% of post-operative sensitivity for direct and indirect inlays respectively. They also reported regarding color match and marginal discoloration where inlays scored better than fillings. Color match and discoloration of the margin were 44%–50% for indirect inlays and 33%–26% for fillings.

Hayashi et al [37] reported on the current trends in the teaching of posterior restorations to undergraduate dental students in Japan by comparing the results of surveys conducted over a 30-year period. In the 2017 survey, 93% (27/29) of the schools reported teaching composite as the preferred choice of materials for the placement of direct restorations in posterior teeth, whereas 65% (15/29) schools did so in the survey of 2007. However, two schools reported teaching metal inlays as the preferred approach even in 2017.

The limitations of our study were that it was an institutional based study, the duration of cases taken into account was only 1 year and very small sample size. Future scope includes taking a larger population into account and populations from different geographical locations.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of the study, age group below 30 years

(64.9%), males (62.2%) and tooth number 37(48.6%) had higher

incidence of patients undergoing class I metal inlay restoration.

Highest number of class I metal inlay restorations were done in

males in tooth number 37. Patients in the age group above 30

years underwent higher number of class I metal inlays in tooth

number 37. However there was no significant association between

age, gender and teeth distribution in patients undergoing class I

metal inlay restoration.

Acknowledgement

The authors of this study would like to express their gratitude

towards everyone who facilitated and enabled us to carry out this

study successfully. We would also like to thank the institute for

helping us to have access to all the case records for collecting the

required cases for conducting this study.

References

- Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Flaxman A, Naghavi M, Lopez A, et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. J Dent Res. 2013 Jul;92(7):592-7.Pubmed PMID: 23720570.

- Rajendran R, Kunjusankaran RN, Sandhya R, Anilkumar A, Santhosh R, Patil SR. Comparative Evaluation of Remineralizing Potential of a Paste Containing Bioactive Glass and a Topical Cream Containing Casein Phosphopeptide- Amorphous Calcium Phosphate: An in Vitro Study. Pesqui. Bras. OdontopediatriaClín. Integr. 2019;19:1-10.

- McCaul LK, Jenkins WM, Kay EJ. The reasons for extraction of permanent teeth in Scotland: a 15-year follow-up study. Br Dent J. 2001 Jun 23;190(12):658-62.Pubmed PMID: 11453155.

- Nascimento MM, Gordan VV, Qvist V, Bader JD, Rindal DB, Williams OD, et al. Restoration of noncarious tooth defects by dentists in The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2011;142(12):1368–75.

- Khalaf ME, Alomari QD, Omar R. Factors relating to usage patterns of amalgam and resin composite for posterior restorations--a prospective analysis. J Dent. 2014 Jul;42(7):785-92.Pubmed PMID: 24769386.

- Correa MB, Peres MA, Peres KG, Horta BL, Barros AD, Demarco FF. Amalgam or composite resin? Factors influencing the choice of restorative material. J Dent. 2012 Sep 1;40(9):703-10.

- Laegreid T, Gjerdet NR, Johansson A, Johansson AK. Clinical decision making on extensive molar restorations. Oper Dent. 2014 Nov- Dec;39(6):E231-40.Pubmed PMID: 24828135.

- Nascimento GG, Correa MB, Opdam N, Demarco FF. Do clinical experience time and postgraduate training influence the choice of materials for posterior restorations? Results of a survey with Brazilian general dentists. Braz Dent J. 2013 Nov-Dec;24(6):642-6.Pubmed PMID: 24474363.

- Newsome PR, Youngson CC. Current status of the cast metal inlay: a survey of dental schools in the UK and Hong Kong. J Dent. 1989 Oct;17(5):222-4. Pubmed PMID: 2621271.

- Hollenback GM. Precision gold inlays made by a simple technic. The J Am Dent Assoc. 1943 Jan 1;30(1):99-109.

- Yamada T. History of metal inlays in Japan Tomomi Yamada and Mikako Hayashi. Dent. Hist. 2019 Jan:27.

- Sturdevant JR, Sturdevant CM. Gold inlay and gold onlay restoration for ClassII cavity preparations. The Art and Science of Operative Dentistry. St. Louis, MO, USA: CV Mosby Co. 1985;490.

- Livaditis GJ. Etched-metal resin-bonded intracoronal cast restorations. Part I: The attachment mechanism. J Prosthet Dent. 1986 Sep 1;56(3):267-74.

- Nandakumar M, Nasim I. Comparative evaluation of grape seed and cranberry extracts in preventing enamel erosion: An optical emission spectrometric analysis. J Conserv Dent. 2018 Sep-Oct;21(5):516-520.Pubmed PMID: 30294113.

- Ramanathan S, Solete P. Cone-beam Computed Tomography Evaluation of Root Canal Preparation using Various Rotary Instruments: An in vitro Study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2015 Nov 1;16(11):869-72.

- Hussainy SN, Nasim I, Thomas T, Ranjan M. Clinical performance of resinmodified glass ionomer cement, flowable composite, and polyacid-modified resin composite in noncarious cervical lesions: One-year follow-up. J Conserv Dent. 2018 Sep-Oct;21(5):510-515.Pubmed PMID: 30294112.

- Ramamoorthi S, Nivedhitha MS, Divyanand MJ. Comparative evaluation of postoperative pain after using endodontic needle and EndoActivator during root canal irrigation: A randomised controlled trial. AustEndod J. 2015 Aug;41(2):78-87.Pubmed PMID: 25195661.

- Teja KV, Ramesh S, Priya V. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-3 gene expression in inflammation: A molecular study. J Conserv Dent. 2018 Nov;21(6):592.

- Janani K, Palanivelu A, Sandhya R. Diagnostic accuracy of dental pulse oximeter with customized sensor holder, thermal test and electric pulp test for the evaluation of pulp vitality: an in vivo study. Braz. Dent. Sci. 2020 Jan 31;23(1):8-p.

- Siddique R, Sureshbabu NM, Somasundaram J, Jacob B, Selvam D. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of precipitate formation following interaction of chlorhexidine with sodium hypochlorite, neem, and tulsi. J Conserv Dent. 2019 Jan-Feb;22(1):40-47.Pubmed PMID: 30820081.

- Ravinthar K. Recent advancements in laminates and veneers in dentistry. Res J Pharm Technol. 2018;11(2):785-7.

- Kumar D, Antony S. Calcified Canal and Negotiation-A Review. Res J Pharm Technol. 2018;11(8):3727-30.

- Rajakeerthi R, Ms N. Natural Product as the Storage medium for an avulsed tooth–A Systematic Review. Cumhur. Dent. J. 2019;22(2):249-56.

- Noor S. Chlorhexidine: Its properties and effects. Res J Pharm Technol. 2016;9(10):1755-60.

- Teja KV, Ramesh S. Shape optimal and clean more. Saudi Endod. J. 2019 Sep 1;9(3):235. =

- Jose J, Subbaiyan H. Different Treatment Modalities followed by Dental Practitioners for Ellis Class 2 Fracture–A Questionnaire-based Survey. Open Dent J. 2020 Feb 18;14(1).

- Manohar MP, Sharma S. A survey of the knowledge, attitude, and awareness about the principal choice of intracanal medicaments among the general dental practitioners and nonendodontic specialists. Indian J Dent Res. 2018 Nov-Dec;29(6):716-720.Pubmed PMID: 30588997.

- Angeletaki F, Gkogkos A, Papazoglou E, Kloukos D. Direct versus indirect inlay/onlay composite restorations in posterior teeth. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2016 Oct;53:12-21.Pubmed PMID: 27452342.

- Olsson SR, Pigg M, Isberg PE; EndoReCo, Fransson H. Demographic factors in the choice of coronal restoration after root canal treatment in the Swedish adult population. J Oral Rehabil. 2019 Jan;46(1):58-64.Pubmed PMID: 30269335.

- Sondell K, Söderfeldt B, Hugoson A. Dental care utilization in a Swedish county in 1993 and 2003. Swed Dent J. 2010;34(4):217-28.Pubmed PMID: 21306087.

- Boslaugh S, editor. Encyclopedia of epidemiology. Sage Publications; 2007 Nov 27:1240.

- Nuckles DB, Hembree JH Jr, Beard JR. The use of cast alloy restorations by South Carolina dentists. S C Dent J. 1980 Fall;38(4):31-4.Pubmed PMID: 6937984.

- Molvar MP, Charbeneau GT, Carpenter KE, Heys DR, Heys RJ. Quality assessment of amalgam and inlay restorations on posterior teeth: a retrospective study. J Prosthet Dent. 1985 Jul;54(1):5-9.Pubmed PMID: 3860657.

- Sandu L, Topală F, Porojan S. Stresses in Cast Metal Inlays Restored Molars. Proc World Acad of SciEng Technol. 2011 Nov 27;5:2142-5.

- Cetin AR, Unlu N, Cobanoglu N. A five-year clinical evaluation of direct nanofilled and indirect composite resin restorations in posterior teeth. Oper Dent. 2013 Mar-Apr;38(2):E31-41.Pubmed PMID: 23215545.

- Pallesen U, Qvist V. Composite resin fillings and inlays. An11-year evaluation. 2003 Jun 1;7(2):71–9.

- Hayashi M, Yamada T, Lynch CD, Wilson NHF. Teaching of posterior composites in dental schools in Japan - 30 years and beyond. J Dent. 2018 Sep;76:19-23.Pubmed PMID: 29474951.